US isn’t first country to dismantle its foreign aid office − here’s what happened after the UK killed its version of USAID

Published in News & Features

The Trump administration’s dismantling of the United States Agency for International Development is unconstitutional, a federal judge ruled on March 18, 2025. The court order to pause the agency’s shuttering came days after Secretary of State Marco Rubio said that 83% of its programs had been cut.

USAID was created in 1961 as the lead agency for U.S. international development. Until recently, it funded health and humanitarian aid programs in more than 130 countries. Despite the administration’s claim of cost-cutting, USAID was a relatively small and economical operation. Its US$40 billion budget accounted for just 0.7% of annual federal spending. Congress also required regular reporting and evaluations on USAID, helping to ensure substantial oversight of how it spent its taxpayer dollars.

USAID’s swift destruction has sent shock waves across the globe. But as a scholar of the global humanitarian aid sector and donor agencies, I know this assault on foreign aid is not unprecedented.

In June 2020, Boris Johnson, then the prime minister of the United Kingdom, used similar claims of budget-tightening to effectively close the Department for International Development, Britain’s equivalent of USAID.

Both the U.S. and British foreign aid programs have long prompted heated debates over the proper relationship between development, diplomacy and national security. The U.S. and Britain have long been among the top five providers of development assistance worldwide, and both USAID and DFID have played leading roles in the development community.

Countries give foreign aid for both altruistic and self-interested reasons. Treating global diseases and addressing civil conflicts is a way for wealthy Western governments to limit threats that could destabilize their countries, as well as the rest of the world. It also burnishes their reputation and encourages cooperation with other governments.

Scholars from across the political spectrum and around the world have questioned the general efficacy of foreign assistance, arguing that these programs are designed to serve the interests of donors, not the needs or recipients. Other development experts contend that foreign aid programs, while imperfect, have still made meaningful progress in improving health, education and freedoms.

Britain’s DFID was created in 1997 as an independent, Cabinet-level department deliberately independent of partisan politics. It quickly developed a reputation as a model donor, even among skeptics of international aid.

For example, a staffer at the international medical charity Doctors without Borders told me in a 2006 interview that he had scoffed at the idea of a politics-free aid agency.

Yet, he said, he had found DFID “relatively easier to work with” than other donors.

“I have never heard of someone being told, as a result of accepting DFID funds, what to do, either explicitly or behind closed doors,” he told me.

But its good reputation could not protect DFID. At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Johnson announced that DFID would merge with the Foreign Office, Britain’s equivalent of the State Department, to create a new government agency. By uniting aid and diplomacy, Johnson said, the new Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office would get “maximum value for the British taxpayer,” and he cited the economic impact of COVID to justify his decision.

Foreign aid dropped sharply after the merger, from 0.7% of Britain’s gross national income to 0.5% – a cut of about US$6 billion.

Development professionals decried Johnson’s merger, arguing it could not have happened at a worse time, with the pandemic heightening the need for global health funding. And coming shortly after Brexit, Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union, DFID’s demise further called into question Britain’s commitment to global cooperation.

Five years later, it’s not clear that dismantling DFID has made British foreign aid more efficient or effective, as Johnson pledged.

“We have seen evidence of where a more integrated approach has improved the organisation’s ability to respond to international crises and events, which has led to a better result,” reads one 2025 report by the U.K.’s National Audit Office.

Yet, the auditors add, the British government has spent at least £24.7 million – US$32 million – to merge its aid and diplomacy offices, and it failed to track these costs. Nor did the leaders of the merger set out a clear vision for its new purpose.

Britain’s slimmer new Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office has also relinquished the U.K.’s past leadership in research and expertise, largely due to pay reductions and restrictions on hiring non-British nationals.

From the outset, DFID had invested substantially in building expertise in global development, particularly in conflict-ridden states. In 2001, for example, it spent almost 5% of its budget – an unusually high amount – on research and policy analysis to design and assess its programs.

DFID produced regular case studies of the projects it funded, which included getting Syrian refugee children back in school, building roads that help Rwandan farmers move their products to market, and providing health care after Pakistan’s 2010 floods.

Given the “development expertise that was lost with the merger,” the U.K. government can no longer conduct “the kind of rigorous, long-term focus necessary to make a real impact,” said the Center for Global Development in a recent report.

A 2022 study suggests that DFID’s dismantling was a fundamentally political move, “divorced from substantive analysis of policy or inter-institution relationships.”

Britain’s new Prime Minister Keir Starmer, of the leftist Labour Party, initially promised to boost British foreign aid. But in early March 2025, he backtracked, announcing instead a further cut to foreign aid.

By 2027, the U.K. government will spend just 0.3% of its budget on overseas aid. That’s roughly $11 billion less than before the merger in 2019.

USAID’s budget was much larger than DFID’s, and the administration apparently wants not to streamline U.S. foreign aid but halt it almost entirely. If this effort succeeds, it will have even more severe effects worldwide, at least in the immediate term.

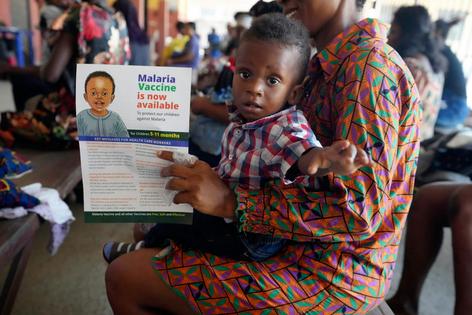

The global health programs administered by USAIDm which combat diseases such as HIV, tuberculosis and malaria, have received bipartisan and global praise. The PEPFAR program, which USAID helps administer, distributes antiretroviral drugs worldwide. It alone has saved 25 million lives over the past two decades, including the lives of 5.5 million babies born healthy to mothers with HIV.

Development professionals tend to see independent government agencies such as USAID and DFID as better able to prioritize the needs of the poor because their programming is run separately from partisan policies.

Yet standalone agencies are also more visible – and so more vulnerable to political targeting.

DFID was a clear and easy target when Johnson began his pandemic-era budget-slashing. USAID is now suffering a similar fate.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Sarah Stroup, Middlebury

Read more:

DfID merger with Foreign Office signals shift from using aid to reduce poverty to promoting British national self interest

USAID’s apparent demise and the US withdrawal from WHO put millions of lives worldwide at risk and imperil US national security

USAID’s history shows decades of good work on behalf of America’s global interests, although not all its projects succeeded

Sarah Stroup does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments