Revoking EPA’s endangerment finding – the keystone of US climate policies – won’t be simple and could have unintended consequences

Published in News & Features

Most of the United States’ major climate regulations are underpinned by one important document: It’s called the endangerment finding, and it concludes that greenhouse gas emissions are a threat to human health and welfare.

The Trump administration is vowing to eliminate it.

Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin referred to the 2009 endangerment finding as the “holy grail of the climate religion” when he announced on March 12, 2025, that he would reconsider the finding and all U.S. climate regulations and actions that rely on it. That would include rules to control planet-warming emissions of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane from power plants, vehicles and oil and gas operations.

But revoking the endangerment finding isn’t a simple task. And doing so could have unintended consequences for the very industries Trump is trying to help.

As a law professor, I have tracked federal climate regulations and the lawsuits and court rulings that have followed them over the past 25 years. To understand the challenges, let’s look at the endangerment finding’s origins and Zeldin’s options.

In 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Massachusetts v. EPA that six greenhouse gases are pollutants under the Clean Air Act and that the EPA has a duty under the same law to determine whether they pose a danger to public health or welfare.

The court also ruled that once the EPA made an endangerment finding, the agency would have a mandatory duty under the Clean Air Act to regulate all sources that contribute to the danger.

The Court emphasized that the endangerment finding was a scientific determination and rejected a laundry list of policy arguments made by the George W. Bush administration for why the government preferred to use nonregulatory approaches to reduce emissions. The court said the only question was whether sufficient scientific evidence exists to determine whether greenhouse gases are harmful.

The endangerment finding was the EPA’s response.

The finding was challenged and upheld in 2012 by the U.S. District Circuit for the District of Columbia. In that case, Coalition for Responsible Regulation v. EPA, the court found that the “body of scientific evidence marshaled by the EPA in support of the endangerment finding is substantial.” The Supreme Court declined to review the decision. The endangerment finding was updated and confirmed by the EPA in 2015 and 2016.

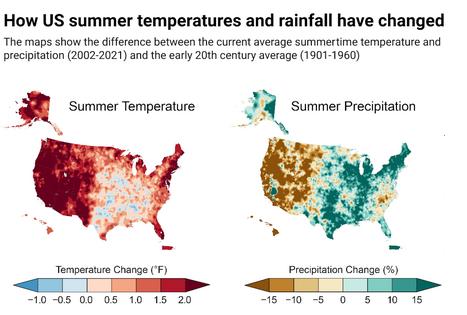

The scientific basis for the endangerment finding is stronger today than it was in 2009.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s latest assessment report, involving hundreds of scientists and thousands of studies from around the world, concluded that the scientific evidence for warming of the climate system is “unequivocal” and that greenhouse gases from human activities are causing it.

According to the National Climate Assessment released in 2023, the effects of human-caused climate change are already “far-reaching and worsening across every region of the United States.”

During President Donald Trump’s first term, then-EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt considered repealing the endangerment finding but ultimately decided against it. In fact, he relied on it in proposing the Affordable Clean Energy Rule to replace President Barack Obama’s Clean Power Plan for regulating emissions for coal-fired power plants.

For the Trump administration to now revoke that finding, Zeldin must first recruit new members of the EPA’s Science Advisory Board to replace those dismissed by the Trump administration. Congress created the board in 1978 to provide independent, unbiased scientific advice to the EPA administrator, and it has consistently supported the 2009 endangerment finding.

Zeldin must then initiate rulemaking in compliance with the Administrative Procedure Act, provide the opportunity for public comment and respond to comments that are likely to be voluminous. This process could take several months if done properly.

If Zeldin then decides to revoke the endangerment finding, lawsuits will immediately challenge the move.

Even if Zeldin is able to revoke the finding, that does not automatically repeal all the rules that rely on it. Each of those rules must go through separate rulemaking processes that will also take months.

Zeldin could simply refuse to enforce the rules on the books while he reconsiders the endangerment finding.

However, a blanket policy abdicating any enforcement responsibility could be challenged in lawsuits as arbitrary and capricious. Further, the regulated industries would be taking a chance if they delayed complying with regulations only to find the endangerment finding and climate laws still in place.

Zeldin previewed his arguments in a news release on March 12.

His first argument is that the 2009 endangerment finding did not consider costs. However, that argument was rejected by the D.C. Circuit Court in Coalition for Responsible Regulation v. EPA. Cost becomes relevant once the EPA considers new regulations – after the endangerment finding.

Moreover, in a unanimous 2001 decision, the Supreme Court in Whitman v. American Trucking Associations held that the EPA cannot consider cost in setting air quality standards.

Repealing the endangerment finding could also backfire on the fossil fuel industry.

States and cities have filed dozens of lawsuits against the major oil companies. The industry’s strongest argument has been that these cases are preempted by federal law. In AEP v. Connecticut in 2011, the Supreme Court ruled that the Clean Air Act “displaced” federal common law, barring state claims for remedies related to damages from climate change.

However, if the endangerment finding is repealed, then there is arguably no basis for federal preemption, and these state lawsuits would have legal grounds. Prominent industry lawyers have warned the EPA about this and urged it to focus instead on changing individual regulations. The industry is concerned enough that it may try to get Congress to grant it immunity from climate lawsuits.

To the extent that Zeldin is counting on the conservative Supreme Court to back him up, he may be disappointed.

In 2024, the court overturned the Chevron doctrine, which required courts to defer to agencies’ reasonable interpretations when laws were ambiguous. That means Zeldin’s reinterpretation of the statute is not entitled to deference. Nor can he count on the court overturning its Massachusetts v. EPA ruling to free him to disregard science for policy reasons.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Patrick Parenteau, Vermont Law & Graduate School

Read more:

America’s clean air rules boost health and the economy − here’s what EPA’s new deregulation plans ignore

Environmental protection laws still apply even under Trump’s national energy emergency − here’s why

The US military has cared about climate change since the dawn of the Cold War – for good reason

Patrick Parenteau does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments