Scott Fowler: Ex-Duke basketball star Mike Gminski abused alcohol for years. Now he's telling his story.

Published in Basketball

CHARLOTTE, N.C. — By the summer of 2020, former Duke basketball star Mike Gminski had been hiding how much alcohol he consumed for years. His drink of choice was vodka.

“Looks like water,” Gminski says now. “Clear. Easy to fool people with.”

What was harder to hide were the vodka bottles stacking up in the recycling bin of the apartment he shared with his 22-year-old son, Noah, in the Cotswold area of Charlotte. Gminski was going through a fifth of vodka a day. Sometimes two fifths.

To get rid of the evidence, Gminski would sometimes walk out behind the first-floor apartment toward a wooded area. When he came to the fence that separated the apartment complex from the woods, he would nonchalantly toss a few empty bottles into the trees.

This worked for a while. But Gminski kept throwing his bottles in the same general area instead of spreading them around the woods, and one day his son discovered them.

By then, a number of the empty bottles were covered with dirt and leaves. But Noah dug them up. And when his father went out to the nearby ABC store to buy some more vodka — the employees knew him well by this point — Noah artfully arranged the bottles. Then he left the apartment.

When Mike Gminski got home, 15 empty vodka bottles were stacked on the kitchen table. It made Gminski feel like collapsing. He’d been caught, and all of the evidence was laid out in front of him. His son was nowhere in sight.

In the midst of the bottles, Gminski found a note.

“Dad, I love you,” it read. “I want to help you.”

Gminski’s new basketball tourney

This weekend was the start of first Mike Gminski Classic — a high school basketball showcase spread across three days at Cox Mill High in Concord. The invited teams were to play a total of 18 games over three days (Friday, Saturday and Monday). The event is run by Phenom Hoops and Sport Mode One.

Gminski planned to be there the whole time. His idea is to share his story, spread the word about the dangers of alcohol addiction and raise some money for the Emerald School of Excellence (a high school supporting teenagers in recovery) and For Students (a non-profit organization that helps students have needed conversations about difficult subjects on their way to adulthood).

Gminski, 65, has been sober for four years.

“My sober date is July 14, 2020,” he says in our interview. “I look forward to celebrating that date each year more than I do my birthday.”

Not long after Noah’s note, an intervention was staged, with the idea of getting Gminski to go to a rehabilitation clinic. This time he agreed. The first time he had not.

In 2017, Gminski’s former Duke basketball teammate Kenny Dennard was among a group of friends who noticed at a gathering that Gminski’s speech was sometimes slurred. His face was flushed. His hands sometimes trembled.

After comparing notes, they tried to get Gminski to go to rehab. Dennard called Gminski on the phone to propose the idea. Gminski called Dennard every curse word he could think of, some of the 12-letter variety, and then hung up.

“Then I went off the grid,” Gminski says.

Phone calls? Unanswered.

Texts from old teammates? No thanks.

The exception? Work.

“I was always a highly-functioning alcoholic,” Gminski says. He’s now in his 31st straight year of broadcasting basketball games. He says he’s never missed calling a game due to being late or hungover. He broadcast Charlotte Hornets games from 1994-2002, then switched to college hoops once the Hornets pulled up stakes and hightailed it to New Orleans since he didn’t want to move to Louisiana, too.

At one point, Gminski called 19 consecutive ACC men’s finals. Nowadays, he does one televised ACC game per week for the CW Network.

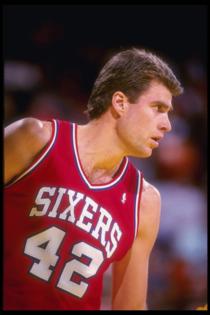

Gminski was — and remains — a genial, knowledgeable broadcaster. He was a three-time All-American at Duke and a three-time academic All-American there, too. Duke retired his number 43. Named the ACC’s Player of the Year in 1979, Gminski was a 6-foot-11, 250-pound highly skilled big man who was also the No. 7 overall pick of the 1980 NBA draft. He put in 14 years in the NBA, guarding Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and teaming with Charles Barkley. At the end of his career, he was a reserve from 1991-94 for some of the Charlotte Hornets’ better teams.

Gminski grew up in Connecticut and graduated high school in three years, at age 16. Decades before anyone had heard of Cooper Flagg, Gminski averaged 15 points and 10 rebounds at Duke as a 17-year-old freshman, then helped lead the Blue Devils to the NCAA final (losing to Kentucky) in 1978 as an 18-year-old sophomore.

But Gminski has never been one to lord any of that over anybody while on the air. He’s likable on the air and easy to listen to — a little bit like yacht radio, and I mean that in a good way. A lot of people call him “G-man,” as Gminski (pronounced Juh-men-skee) is a little hard to say if you aren’t old enough to remember his career. He’s been an acquaintance for years and is known in sports media circles as a good guy who’s talented at most everything he’s tried. I don’t know him well, but always thought that he made life look pretty easy.

Outside of basketball arenas, I saw Gminski in the crowd at concerts in Charlotte a few times. At 6-11, he sticks out. He always had a drink in his hand. Then again, so did most everyone else.

Drinking from age 15

Gminski was around alcohol in earnest starting at age 15.

“We played pickup games in our park,” Gminski says. “The liquor stores in Connecticut closed at 8 p.m. The courts were lit. So at 7:45, the guys who were of age would go buy the beer and then come back and play. We’d play until 10 or whatever, then sit around, drink beer and go home.”

At Duke, Gminski stuck with beer. In the NBA, it was mostly the same thing. The alcohol never affected his play, he says. He’d play an NBA game, walk out of the locker room at 10:30 p.m. and still be wired. Six or seven beers would take the edge off. Then he’d go to practice the next day and sweat it all off.

He started drinking more when his NBA career ended and his broadcasting career began. There were still games. But suddenly, there was no need to practice anymore.

“There was just so much time,” Gminski says.

Gminski occasionally used cocaine earlier in his life, too, he says. He never got addicted to it, and it was only an occasional thing, but what he liked about the drug was that it seemed to make him be able to handle drinking even more.

In the 2000s, Gminski’s marriage broke up. As it was ending, he met a woman named Sarah Culpepper in Charlotte. She was a native Charlottean and 23 years younger than Gminski. He worried that the difference meant that he would die long before she did.

But they were in love. In 2013, they got engaged.

Then, at the beginning of 2015, Culpepper wasn’t feeling well. She suffered from a congenital heart condition and had liver issues. In February, in the apartment they shared, Gminski found her unresponsive.

“She had a massive internal hemorrhage,” Gminski says, “and she died right in my arms while I was trying to save her.”

Sarah Culpepper was 32 years old when she passed away. Gminski was 55, and adrift.

The ACC and TV communities who heard about the tragedy embraced Gminski, who returned to work after the funeral. His Duke teammates reached out. UNC’s entire basketball team and coaching staff personalized a card for him. In his office, UNC coach Roy Williams cried along with Gminski.

“That’s what people don’t get about all the Duke-UNC stuff,” Gminski says. “There’s the on-court part where you want to kill each other, and then there’s what you do for each other off the court.”

But even with friends in his corner, Gminski spiraled downward. People pretended not to notice.

“Everyone gave me about a two-year hall pass to grieve,” Gminski says. “And things really escalated after Sarah died. My brain short-circuited. And I didn’t seek help, because the athlete in me was too proud to ask for help. ... So I self-medicated.”

Did Gminski ever get arrested anywhere for DUI or any other alcohol-related charge? He says he did not, and I found no evidence to the contrary.

Did he ever drive when he was inebriated?

Oh yes. Many times.

“That’s what I’m most ashamed of,” Gminski says. “All of the people I endangered on the road.”

In 2017, Dennard and company couldn’t get Gminski to agree he had a problem. In 2020, he made it through the end of the ACC regular season — barely. Then COVID came, and other than the vodka bottles behind the trees, it was pretty easy to hide things.

‘I’ve decided to be open’

After his son’s note and the ensuing intervention, Gminski went to former NBA player Jayson Williams’ treatment center called Rebound in Lake Worth, Fla. He would return the next two years for several months at a time, as a peer mentor who could help people going through what he had so recently experienced. He took medicine that helped him subdue his craving for alcohol. He got comfortable telling his story, first in private and then later in public. He made himself available to counsel people at his Charlotte church, called Moments of Hope and led by former UNC basketball player David Chadwick. He accepted wise counsel from Phil Ford, the UNC star who competed with Gminski in the late 1970s and also struggled with alcohol.

Gminski’s Christian faith strengthened, so much so that Gminski’s arms are now covered with spiritual tattoos. One of the few secular exceptions is on his left shoulder, where a Duke Blue Devil is inked, along with the word “brotherhood.”

Another is a giraffe.

It turns out that his grandson, Asher, was born prematurely and spent a week in the hospital. During that time, the blanket that kept him warm was covered with giraffes.

Gminski says that this phase of his life will be dedicated to others struggling with addictions. He works now during the week for Sana House, a recovery residence for men ages 18 and up who need a place to stay between rehabilitation and re-entering the world. Then he calls a basketball game on most weekends. Not this weekend, though. He was at his high school basketball tournament, ready to talk about his life to anyone who asked.

“I’ve decided to be open about my story and my journey and where I am,” Gminski says.

Gminski has counseled dozens of people over the past few years through the darkness he experienced. So what should you do if you or someone you love might have a problem with addiction yourself?

“My first thing is that if you think you have a problem, you do,” Gminski says. “And the second thing is there’s no shame in that. And that’s the biggest thing to overcome. There is no weakness in asking for help. I was too prideful and my ego got in the way for years. ... Especially as a man, you’re not conditioned to talk about your problems or ask for help. It’s ‘Rub some dirt on it. Get back in there.’

“But I’ve found sharing my story and my issues to be empowering. So you have to say ‘I need help’ to someone you trust. And, if you think someone needs help, approach them.”

But isn’t that hard to do? Gminski, after all, turned down help from his Duke brotherhood in 2017. It was three more years before his only child broke through to him with the dirty vodka bottles in 2020.

“Just the offer, though,” he says of Dennard’s first call. “It made me start thinking. It started a clock ticking somewhere. If you think someone needs help, it’s worth taking the chance.”

©2024 The Charlotte Observer. Visit charlotteobserver.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments