Former Phillies general manager Ed Wade became a novelist to fill the void after leaving baseball

Published in Baseball

PHILADELPHIA — Ed Wade spent the days leading to Christmas making trades, signing free agents and manicuring the Phillies roster as the team’s new general manager.

The 1997 season had ended weeks earlier, and 1998’s opening day was still months away. It was baseball’s offseason, but the general manager was not off. There was always a decision to make, even on Christmas Eve.

“I remember my wife, Roxanne, saying, ‘Is it always going to be like this?’ ” Wade said. “I said, ‘Yeah. It’s sort of going to be.’ ”

Wade started his baseball career the day before his 21st birthday. He accepted an internship with the Phillies before he graduated from Temple in 1977. His life was then dictated by the rhythms of the game, which he learned can be incessant as he completed a deal in December 1997 with the Chicago Cubs a few hours before Santa arrived. That’s how it was.

When it came to an end eight years ago, the baseball man had to find something to fill the void left by the game. The Phillies let Wade go from his scouting role after the 2017 season. The guy who once made trades on Christmas Eve had time on his hands.

“I’m not a golfer. I run, but I can’t run forever. So I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do,” said Wade, 68. “I had an idea.”

He published a novel in 2012, a project he started after the Phillies fired him as general manager following the 2005 season. Wade put his pen down when Houston hired him in September 2007 and then finished the book after he lost that job. It was a way to pass the time. So when Wade lost his job in 2017, he decided to write again.

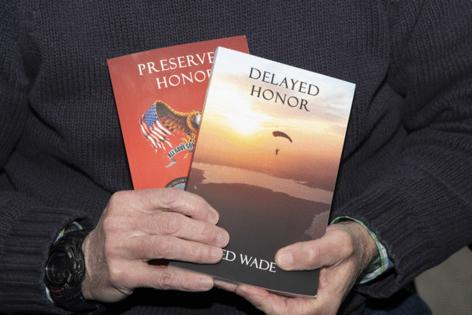

His latest book — "Preserved Honor" — was released in November and is the follow-up to 2012’s "Delayed Honor." Wade, who lives in Washington Township, N.J., spent his life in baseball, but the books have nearly nothing to do with the game he loves. They instead are military-inspired mystery novels that take place in a fictional Pennsylvania town based on where Wade grew up in Lackawanna County.

The characters are drawn from people Wade met over the years, like a U.S. Navy captain who was a prisoner of war in Vietnam and the Navy SEALs who taught him how to skydive. A priest is based on the former pastor of the Catholic church Wade attends in Pitman, N.J. For a guy who spent his life in baseball, the world he created was an escape when the game stopped.

“If someone wants to read it, that’s fine. But I didn’t do it for the money or the adulation,” said Wade, whose books are available on Amazon. “I did it as a mental exercise. I did it for something that could eat up a lot of time and a lot of reams of paper. I’m happy I got to the finish line.”

From sportswriter to GM

Wade spent eight seasons as Phillies general manager, leading a front office that drafted or acquired most of the key players of the 2008 World Series champions. Wade’s teams never reached the playoffs, but they would have twice under the current format.

Before that, he dreamed of being a sportswriter. Wade left Carbondale, an old coal-mining town near Scranton, in the early 1970s to study journalism at Temple and walked on to the school’s baseball team.

“It was a godsend that I went to Temple because I think Skip Wilson was probably the only Division I baseball coach in America who never cut a player,” Wade said. “I didn’t get cut, but I think I began my player evaluation career by self-evaluating and realizing after 2 1/2 years of playing, I had to graduate on time.”

No longer a ballplayer, Wade hustled to become a ball writer. He interned at the Philadelphia Bulletin and the Associated Press. He spent a summer at the Williamsport Sun-Gazette and appeared to have a job in Scranton.

But then the Phillies offered Wade a spot: a $2.50-an-hour internship for the 1977 season. Wade became friendly with Larry Shenk the previous season after pestering the team’s public relations director for a press pass. Shenk gave Wade a chance.

The future GM interned that summer in the press box and met his wife while standing at the Veterans Stadium elevator. The Phillies didn’t have a job after the season, but Shenk wrote a letter of recommendation to every other team.

Bill Giles gave him tickets to the World Series at Yankee Stadium — all the Phillies employees were too despondent to go after being eliminated days earlier — and paid for his train ticket to New York City. Wade met there with the PR director of the Houston Astros, who offered him a job for the next season.

Wade watched from the seventh row behind home plate as Reggie Jackson became Mr. October. His career was ready to begin.

Credit for 2008

Shenk wrote to Wade in the summer of 1977 that his request for a press pass was declined because the college student was not a member of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. Wade, refusing to be denied, wrote a letter to the association’s president and asked how he could join. The Chicago baseball writer told him to talk to Ralph Bernstein, a longtime sportswriter for Philly’s AP bureau.

Wade was working in Williamsport and knew Bernstein called the Sun-Gazette office every Friday night. He waited by the phone and told Bernstein about his denial from the Phillies. The writer told him to call when he returned to Temple and he’d have Shenk leave him a pass. Wade used it, asked for another, and went again.

“I’m sitting here right now looking at a fancy rocking chair with monk heads carved on the arms,” Wade said. “It was found in some antique store by Tug McGraw and he bought it for Paul Owens because he thought the monk heads looked like him. Pope’s family gave it to me after he died. Why do people like [Houston’s] Tal Smith and Bill Giles and Dallas Green take an interest in me? I’m sure there are a lot of people who strain their muscles patting themselves on the back, but I’m just grateful to everyone who gave me a chance.”

Wade did not take a conventional way to the GM box as he worked mostly in public relations before returning to Philadelphia from Houston in 1989 to be an assistant general manager. He was elevated eight years later to the top job. He was back in Houston when the 2008 Phillies reached the World Series, but GM Pat Gillick credited Wade as the National League trophy was presented and the players sprayed champagne.

“A lot of the credit for this celebration tonight should go to Ed Wade,” Gillick said. “He put together a lot of this team. Three-quarters of our infield, Cole Hamels, Pat Burrell, they’re all his guys. I kind of filled in around what Ed had in place, so a lot of credit should go to Ed Wade and his group because they did a tremendous job getting the nucleus here in Philadelphia.”

Wade was at home, and his phone started buzzing. Gillick’s comments, he said, meant a lot. Yes, Wade’s teams fell short of October, but now even the Hall of Fame architect of the team that became world champions later that month was giving him credit. Wade knows the credit belonged to more than him. He says Mike Arbuckle, Marti Wolever, the scouts, and the rest of the front office played roles that were just as important.

“One of the things I take pride in is that I think I did a pretty good job of listening to our people and giving them the opportunities to do what they were capable of doing,” Wade said. “I go back to my Carbondale roots; it’s easy for people to pat themselves on the back.”

It all started with a kid from Carbondale who wanted to be a writer. And now that former GM is a writer, again.

“I needed something to do,” Wade said. “The longer I sat banging away at the computer, the more sense it made to continue going forward. If anyone wants to buy it, that’s fine. If they don’t, that’s fine, too. But it accomplished what I wanted to do and be able to sit down and do something other than fret over the amount of money we had to spend on free agents or how we’re going to put this roster together.”

©2025 The Philadelphia Inquirer. Visit inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments