Fires, wars and bureaucracy: The tumultuous journey to establish the US National Archives

Published in Political News

Some of the United States’ most important historical documents, including the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Bill of Rights and the Emancipation Proclamation, are housed in the U.S. National Archives. Beyond these high-profile items, it also preserves lesser-known but no less vital records, such as national park master plans, polar exploration documents and the records of all U.S. veterans. Together, these materials stand as a testament to the country’s commitment to preserving its history.

While these crucial documents in U.S. history now have a home in the National Archives, the road to establishing this institution was paved with catastrophic losses and bureaucratic inertia.

Creating the National Archives required decades of advocacy by historians, politicians and government officials. The National Archives was not simply an administrative convenience – it was a necessity born from repeated disasters that underscored the fragility of government records. And with President Donald Trump’s firing of the head archivist in February 2025, as well as the loss of several high-level archives staff members, the organization faces a new era of uncertainty.

Documentary heritage – the recorded memory of a nation that preserves its cultural, historical and legal legacy – is essential for a country as it safeguards its identity, informs its governance and ensures that future generations can understand and learn from the past.

I am a university archivist with two decades of experience in the library and archives field. I oversee the preservation and accessibility of historical records at Rochester Institute of Technology, advocate for inclusivity, and engage in national conversations on the evolving role of archives in the digital age.

Understanding the precarious nature of historical records, it’s clear to me that maintaining, staffing and funding the National Archives is a necessary safeguard against the destruction of the nation’s documentary heritage.

The idea of preserving the government’s records dates back to the country’s founding. Charles Thomson, secretary of the Continental Congress during the American Revolution and then secretary of Congress under the Articles of Confederation, recognized the need for proper storage of the Congress’ records.

But the young nation lacked the money and infrastructure to act. Many of the Continental Congress’ records were kept by Thomson himself for years, and while some were later transferred to the Department of State, others were lost.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, fires repeatedly ravaged federal records. Fires were very common in the 19th century due to a combination of highly flammable building materials, open frames used for lighting and heating, and the lack of modern fire safety measures such as sprinklers and fire-resistant construction.

In 1800, a blaze destroyed the War Department’s archives, a loss that severely hampered government operations. In 1810, Congress authorized better housing for government records, but the law was never fully executed. Instead, different parts of the government, from the Department of State to the Department of Treasury, continued maintaining their own records.

The Treasury Department suffered fires in 1801 and again in 1833, further erasing crucial financial records. The Patent Office, home to invaluable documentation of American innovation, burned in 1877, having already been damaged by an 1836 fire.

One of the most devastating losses occurred in 1921 when a fire at the Department of Commerce destroyed nearly all records from the 1890 federal census. This loss had far-reaching consequences, particularly for genealogical and demographic research.

Fires weren’t the only threat to the government’s records.

“It is a matter of common report that during the civil war, great quantities of documents stored in the Capitol were thrown away to make quarters for soldiers,” Historian and founding member of the American Historical Association J. Franklin Jameson noted in a 1911 Washington Post article.

“At a later date,” he added, “the archives of the House of Representatives were systematically looted for papers having a market value because of their autographs.”

Jameson spent decades lobbying Congress for a centralized repository. His persistence, coupled with the advocacy of key officials, laid the groundwork for future action.

These repeated disasters illuminated a glaring issue: The federal government lacked a centralized, protected repository to safeguard its records.

Momentum for a dedicated archives building gained traction in the late 19th century. In 1903, a bipartisan bill passed Congress giving the OK to purchase land in Washington, D.C., for a Hall of Records.

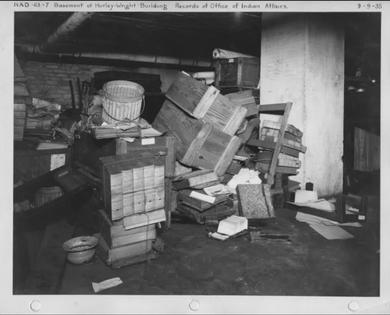

But the legislation didn’t lead to any action. Government records remained scattered, vulnerable and neglected. That same year, Congress authorized that any records not needed for daily business be transferred to the Library of Congress.

In 1912, President William H. Taft issued executive order 1499, aptly named Disposal of Useless Papers, requiring agencies to consult the librarian of Congress before disposing of documents.

This established a formal review process for government document disposal, but agencies still discarded records, often haphazardly, until stricter records management laws were enacted.

In 1926, Congress passed the Public Buildings Act, authorizing construction of an archives facility in Washington, D.C. Departing president Herbert Hoover laid the cornerstone of the new building on Feb. 20, 1933. He then deposited facsimiles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, an American flag and daily newspapers from that day underneath the cornerstone.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who took office two weeks later, was himself a meticulous record-keeper. He understood the importance of historical preservation. Roosevelt kept all of his personal and presidential records and books in a fire-safe space he built on his Hyde Park, New York, property, which he donated to the government after he died. This building and the materials inside became part of the National Archives as the first U.S. presidential library.

The National Archives, an independent agency, was officially established under Roosevelt in the 1934 National Archives Act. The head archivist was to be appointed by the president. The first archivist, Robert D.W. Connor, took office that year with a mandate to organize, preserve and make accessible the nation’s records.

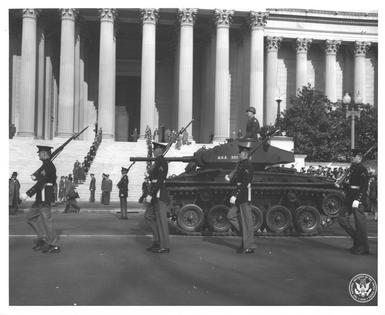

Initially, the National Archives was simply a building – an impressive neoclassical structure in Washington, D.C., that opened in 1935. The very first records deposited there came from three World War I-era regulatory agencies – the U.S. Food Administration, the Sugar Equalization Board and the U.S. Grain Corporation.

Initially, the Archives lacked a formalized records management program. There were no clear guidelines on what to keep and what to discard, so agencies made their own decisions. This led to inconsistent preservation.

The creation of the first federal records administration program in 1941, together with the 1943 Records Disposal Act, codified things. These policies granted the National Archives authority to establish a structured approach to determining which records held historical value and should be preserved, while allowing for the responsible disposal of other documents.

A 1950 law gave the National Archives more power to decide what should be kept and what could be discarded, creating a more organized and accountable system for preserving the nation’s history.

As the volume of records increased and their formats changed, the archives adapted. By 2014, amendments to the Federal Records Act explicitly included electronic records, recognizing the shift toward digital documentation.

Beyond mere storage, the National Archives plays a vital role in upholding democracy.

It ensures transparency by preserving government accountability, preventing manipulation or loss of records that could distort historical truth. The National Archives also provides public access to documents that shape civic awareness and historical knowledge, from the Declaration of Independence to declassified government files.

In an era of digital misinformation and contested narratives, the National Archives stands as a guardian of primary sources. Its existence reminds the nation that history is not a matter of convenience, but a cornerstone of informed governance.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Elizabeth Call, Rochester Institute of Technology

Read more:

How the FBI knew what to search for at Mar-a-Lago – and why the Presidential Records Act is an essential tool for the National Archives and future historians

How curators transferred Sequoia and King’s Canyon National Parks’ archives to escape wildfires

Trump wants the National Archives to keep his papers away from investigators – post-Watergate laws and executive orders may not let him

Elizabeth Call is a member of the Society of American Archivists.

Comments