It started with a book about adoption: How DNAngels helped in decades-long journey to find biological parents

Published in Parenting News

Children get all kinds of books from their parents while growing up. But a book mine gave me when I was around 10 years old would have a significant impact on my life — even if I didn’t realize it at the time.

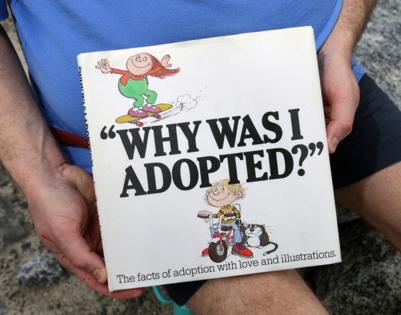

It was around 1980 when they gave me “Why Was I Adopted?” by Carole Livingston. The book is meant to help parents like mine answer questions children frequently ask when told they’re adopted.

Now, at 54, I really don’t recall much from when they told me or any questions I asked them. Recently, I asked my mother why they adopted me instead of having a second biological child, and she told me it was because they knew there were children who needed homes. She said they told me about it because keeping secrets like that can only lead to problems later in life.

For more than four decades, I wondered why I was given away and who my original “mom” and “dad” were. I thought about the family that might have been. But it wasn’t until this year that I finally got answers.

With the help of DNAngels (pronounced DNA Angels), an Illinois-based nonprofit I learned of on Facebook, in late January, I discovered the identity of my biological parents — my mother is 75, and my father died in 2009 at 62. I have a half-brother (born June 1981) and half-sister (born June 1971), along with six nieces and nephews (ages 16 to 30) and many cousins.

DNAngels is a 501(c)3 nonprofit whose staff of almost 100 volunteers helps people find biological parents at no charge using DNA and research — additional fee-based services are available. It was founded in 2019 by Laura Olmsted, its executive director, and relies entirely on funding and in-kind donations from foundations, corporations and individuals.

In February 2018, I took a DNA test from Ancestry, and the results revealed many matches — some as close as first or second cousins. These were the first “blood” relatives I ever knew, but exchanging messages on the site with some of them over several months didn’t lead anywhere. Then, the COVID-19 pandemic struck in 2020, and I stopped thinking about finding my biological family until 2024.

It was Jan. 22 when I reached out to DNAngels after seeing its Facebook ad in my feed upon joining a group for people from Michigan seeking information about their biological parents. Its volunteers took my Ancestry DNA test results and matches, then used their knowledge of genealogy along with research tools to put together my origin story.

They started working on my case early in the afternoon on Jan. 23, and about seven hours later, my “lead angel” was sharing with me details of what she’d discovered. By Friday morning, I had learned who my biological father was; I was talking on the phone with my birth mother and later in the day with my half-brother and half-sister (all of us have different fathers).

Where things began

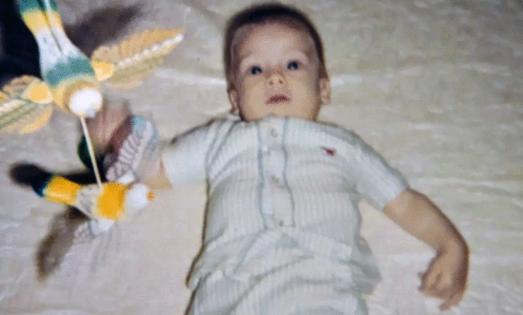

I was born Feb. 22, 1970, at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak to Nancy Brown, 20, of Ferndale (I now live in Volusia County). She never held me and only got a glimpse of me as I was wheeled out of the delivery room in a bassinet, but she remembered that I had a very full head of hair. A high school friend, another Nancy, who drove her to the hospital while in labor, saw me and told her I had the longest legs she’d ever seen on a baby (I guess that explains my height of 6 feet, 6 inches).

Nancy said that when she realized she was pregnant, she knew right away that she wouldn’t keep the baby. Her mother pressured her to give up the baby, too.

“That was what I wanted to do right from the get-go,” she said. “I knew I just didn’t want to bring you home.

“I was 20. I had a big social life. I liked the boys, and the boys liked me. So I thought, ‘Hey, have a baby, give it away to somebody who probably couldn’t have children, so I could go back to my own life.'”

Although she didn’t keep me, she did give me something when I was born — even if it was only temporary.

“(The doctor) asked me what I was going to name you, and I said I wasn’t keeping you. He said, ‘Well, you have to give him a name.’ He said, ‘How ’bout we name him George?’ I said OK,” Nancy recalled. “That was the doctor’s name. And then it didn’t occur to me, but that was also George Washington’s birthday.”

So I was George Brown until weeks later when a married couple in their mid-20s adopted me from the agency I was placed with and renamed me Brian.

Nancy grew up in Ferndale and, as an adult, lived in other states, including Florida, New Jersey and North Carolina. She was married three times and last divorced in 1992. She moved into her current house in Hazel Park, which borders Ferndale, in 1991. Both cities are just a few miles from the house in Madison Heights, where I grew up and lived until 1988 when my parents moved.

Nancy told me it was May 1969 when the other Nancy (who she’s still friends with) introduced her to her neighbor Clyde DeLong Jr. — my biological father. They went on one date, and I was the only lasting result. About six weeks later, Nancy saw Clyde again and told him she was pregnant, but he denied he was the father. She never saw or heard from him again.

After I was born, Nancy said she remained in the hospital for five days because, back then, that’s how long the baby stayed. On the day she left, she was at a party that night.

“I was at an aunt and uncle’s 25th wedding anniversary that night,” Nancy said. “I didn’t feel so good, and because I had kept the pregnancy pretty secret, I had put on a girdle and went to the party.”

She said it wasn’t until my sister was in her 20s that she revealed to her she wasn’t the firstborn child.

“We were in a restaurant, and her and I were arguing about something at the table, and I said to her, “Well, at least I kept you!’ and she said, ‘What?'” Nancy recalled.

She said in the 1990s, she and my sister went to the Oakland County courthouse (the county where I was born) in Pontiac and filed paperwork — with their names and other personal information — giving permission to release it to me if I came seeking it. But the idea of doing that never occurred to me.

“I didn’t have any problem with you finding me,” Nancy said. But she admits that after the passing of so many years, she didn’t think she’d ever hear from me. “I always thought once I filled out that paperwork and never heard a thing in years, and years went by, that you didn’t even know you were adopted or that you were dead.”

Ready to meet

I knew quickly that if I felt things with Nancy were going well, I’d want to fly to Michigan to meet her and other relatives. By late March, I was ready and booked a flight out of Orlando International Airport for April 29. I spent 10 days meeting my new family as well as visiting with my parents.

I arrived at Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport around noon and, about two hours later, was in my Airbnb in Ferndale — just a couple of miles from where Nancy lived. At 5 p.m. I pulled into her driveway to meet for the first time before going to dinner.

I brought her flowers, and we hugged, but I didn’t get as emotional as I thought I would in the moment. I jokingly told her the only thing that would’ve made finding her any better was if she’d been wealthy, and she retorted that it would’ve been nice if I’d been a doctor instead of a journalist.

Most of my time in Michigan was spent getting to know Nancy, learning more about our ancestors and meeting relatives. We had several get-togethers, including lunch with my sister (my brother didn’t show, so we never met), breakfast with one nephew, breakfast with a group of cousins and a gathering at my oldest niece’s apartment, where I met her husband, another niece and nephew as well as my sister’s husband. I also met the other Nancy, who was there when I was born.

One day, Nancy took me to the neighborhood where she grew up, and we visited a cemetery where many relatives are buried, including her mother. Then I took her to the neighborhood where I grew up, and we even walked in the woods right behind my childhood home. I also showed her many photos of myself growing up so she could get a glimpse of my childhood.

I returned to Florida on May 8. I recently asked Nancy about the experience of reuniting with the son she gave away.

“I mean, it was a little strange,” she said. “Well, I mean, you didn’t look like the other two, but all my kids have different fathers.”

She pointed out that, like her other children and herself, we’re all tall and have big feet. Her parents were also tall — but I’m the tallest among my immediate family.

Nancy and I still talk by phone regularly, and the relationship seems to be going well — I’ve invited her to come visit me in January.

As far as my brother and sister, we haven’t talked since my visit — neither seem interested in a relationship, but that’s nothing new for me. I have another sister — my parents’ biological child who’s almost four years older — and we haven’t had any kind of relationship in decades. I was a handful growing up, and I’m sure that has something to do with why we haven’t talked or seen each other in more than 20 years.

Searching begins

As much as I thought about finding my biological family over decades, the idea of navigating the Michigan legal system to open a sealed adoption record seemed daunting. For adoptions between May 28, 1945, and Sept. 12, 1980, you can’t get an original birth certificate without a court order. Arizona is the only other state that has similar laws. However, Michigan legislators are trying to change the law to make it easier for adoptees to get information.

Discovering DNAngels had me cautiously optimistic. I did a little investigating on Google to see what others had to say about it, and I found only positive reviews. I then went to the website (DNAngels.org) and filled out a short form requesting a “search angel.”

On the evening of Jan. 22, I went through a short screening process (about 30 minutes) on Facebook Messenger with a volunteer and provided her with screenshots showing top matches from my Ancestry DNA test. After looking those over, she told me DNAngels would take me as a client.

I then shared my raw DNA test results and access to my family tree on Ancestry with her, and she sent me an invitation to DNAngels’ private Facebook group of current and former clients. I joined it and was now on the waitlist for someone to start working on my case. But I didn’t have to wait long.

On Jan. 23 at 1:56 p.m. I got a message saying Katharine Saunders was assigned “lead angel” and would begin work soon. Communication takes place through Messenger, which ensures there’s a record of conversations you can look back at even after work is done. For those without Messenger, communication can take place by email, but I was told the process is quicker using Facebook.

Saunders, 42, a married mother of three young children who lives in Texas, started volunteering with DNAngels in 2022. In early July, she left her position to focus on her family, but during her time with the group, she said she helped identify over 160 birth parents.

Saunders said she’s been involved with genealogy most of her life. She and her mother spent years working with DNA testing to check the biological accuracy of a family tree her maternal grandmother created long before computers. During the pandemic, Saunders took formal genealogical training courses online through Boston University and the Salt Lake Institute of Genealogy.

At 2:04 p.m., she told me work was getting underway and generally takes a few days for results. My response: “I’ve waited decades now, so a few days won’t matter.”

A few minutes later, she provided an overview of how the process works.

Saunders told me it starts by sorting matches from Ancestry into groups to establish my line of grandparents. Then she starts linking matches to each other based on their common ancestors and placing them onto a new family tree on Ancestry, which eventually leads to my most recent common ancestor.

“We’re making connections. I can give you a general ‘Where are we now’ later this evening. It’s still early stages,” she told me at 4:52 p.m.

At 9:02 p.m., Saunders told me: “I believe we may have identified your Birth Mother. When you have about 30 minutes, please let me know, and I can tell you what we have determined.”

A short time later, I finished work for the day and told her I was ready to learn what she’d discovered.

Saunders said the first thing the team did was sort matches into groups. On the side of “Parent two,” my birth mother, she said the team identified two main groups of DNA: one from Florence Knights and John Brown Sr. (my paternal great-grandparents) and the other from Walter Cullingford and Hannah Turner (my maternal great-grandparents).

She told me John Brown Jr. (1923-1994) and Shirley E. Cullingford (1921-1998) were married Sept. 7, 1946, in Detroit and divorced in 1951 (they were my maternal grandparents). On the 1950 census, they listed one child — a daughter named Nancy Brown. The team believed she was most likely my birth mother.

“We found an address for Nancy and her mother Shirley in Hazel Park, Michigan, which I believe is very close to where you were placed for adoption,” Saunders said. “And it looks like Nancy is still alive and has a son.”

In the course of her research, Saunders utilized programs such as What Are the Odds to determine if her hypotheses were likely. WATO analyzes relationships to individuals based on amounts of shared DNA expressed in centimorgans. A centimorgan is a genetic unit of measurement utilized by genetic genealogists to determine how closely two people might be related.

Now that I knew the identities of the people, Saunders provided me with background reports on Nancy and her son, which included addresses, emails, phone numbers, first-degree relatives as well as social media accounts and criminal history. The reports are based on publicly available information, and she said the goal was to equip me with the necessary details to establish meaningful connections.

Things were more complicated when it came to identifying my biological father.

“One side is French Canadian, which means we need to go into records written in French,” Saunders told me via Messenger. “The other side looks probably Polish, which also presents a complication due to a lack of records from that country. But we are working on it.

“We don’t close anything when we’re working adoptions until we’ve solved both sides.”

Reaching out

The next step for me was to decide how to reach out to Nancy. I could do it myself using information from the background report, or for a $125 donation, use DNAngels’ liaison service, and a trained volunteer would reach out on my behalf. I went with the liaison because I was nervous about doing it myself.

A volunteer named Ashlee Krump, research team lead at DNAngels, would be my liaison and on the afternoon of Jan. 24, she explained to me how the process works.

First, the team does all it can to verify they have the correct contact information. Then she starts calling, and if she gets her on the phone, she’d “delicately” explain the situation and whatever my goal is for having contact and help facilitate that. If attempts to contact her by phone were unsuccessful, she’d attempt to reach her by email and then, eventually, after a few days, use regular mail deliverable only to her with a signature. She told me around 8 p.m. she’d start calling the next day.

At 3:53 p.m. Jan. 25, she sent me a message: “I believe we have the correct number! Her voicemail identified her by name, and her voice sounded in the correct age range. I am going to try calling again in an hour or two. If she still does not answer, I will leave a message for her.”

I told Ashlee I was curious about what kind of voicemail message she leaves in this type of situation.

“I usually introduce myself and say who I am trying to reach and mention a relative’s name, such as her parent or grandparent, ‘I am trying to reach Nancy Brown, the granddaughter of … ‘ — and let them know I am trying to get a hold of them regarding a family matter that is easier to explain over the phone, but I am happy to speak over text or email if they prefer. This helps to disarm them a bit and alleviates some concerns about scams/spam. People tend to be less defensive and more curious.”

Ashlee said she left a voicemail with her phone number and kept her phone on her day and night — that way, Nancy could reach out anytime. I went to bed that night, hoping for the best. And the next morning, I woke up to a message she’d sent at 2:17 a.m.

“Hi, Brian! Wonderful news! I heard back from Nancy. She is very happy to speak with you! She had been wanting to find out more about you as well. She told me your father’s name is Clyde Delong, who was from Tennessee. He was visiting Michigan, and they had a one-night stand. Clyde did not believe he could be your father when she told him. Katharine will work on verifying he is the correct person via DNA (sometimes memories can be wrong, but Nancy was very upfront and honest, so I have no reason to believe she’d give the wrong name on purpose). She has a daughter born in 1971. Nancy said that her mother put a lot of pressure on her to have you adopted, mainly because she was so young. Nancy is going to send you a text and then call you when you are available Friday.”

When Nancy first got the call from Ashlee, she saw on her caller ID it was from an unrecognized number in Oregon. She told me she didn’t know anyone from there, so she blocked the number. Later, she saw that she had a voicemail message, so she went ahead and listened.

“She repeated two names, and she said, ‘Are these my parents?’ and I was like dumbfounded, why are you mentioning my parents?” Nancy said. “So I looked at the clock, and by then, it was like one o’clock in the morning my time, and I thought, well, what the heck, I don’t care.”

She called the number, and Ashlee answered. Nancy told her who she was, and Ashlee explained why she’d called. After the call, around 2 a.m., Nancy called her daughter and woke her up to share the news: “All I said was your brother’s name is Brian, and he lives in Florida. And that woke her up.”

The next morning at 11:19 a.m. I received a text message from Nancy.

“Hi Brian my name is Nancy and as you might have been told already I gave birth to you at Beaumont hospital in Royal oak on February 22nd 1970 I want to leave everything up to you so call or text me when you feel up to it. I am on my way home from work right now.”

I called her right away, and over the course of the day, I talked and texted with her, my brother and my sister.

Nancy confirmed that Clyde was the father, and Saunders was then able to explain why she couldn’t say earlier that research showed he was likely my birth father.

“We actually already had Clyde Delong in your tree before your birth mother named him,” she said. “But we didn’t have enough proof at the time to present him as a birth father candidate.”

DNA revealed that another man who also served in Germany in the Quartermaster Corps with Clyde’s father was his actual biological father and not the man listed on his birth certificate.

“We do not know if the family has any idea about this,” Saunders said. “But that is a very common discovery in this work as we let the DNA lead the investigation.”

I don’t know a lot about Clyde, but information gathered by DNAngels indicates he had no other children and all his siblings or half-siblings are deceased. He died Aug. 2, 2009, in Glynn County, Georgia, at 62.

Ready to help

For others like myself who seek answers to questions about their biological family, Olmsted, DNAngels’ founder, said the organization takes most cases.

One requirement is that you have results from an Ancestry DNA test. That’s because Ancestry has many millions more test results than other sites, and most of its matches are linked to family trees. The trees of shared matches have a common ancestor, and DNAngels uses that to narrow its focus to a family tree.

Another requirement is that clients search for a biological parent in the countries it serves — the United States, United Kingdom, Australia and Puerto Rico.

Since DNAngels’ inception, the organization has taken on more than 7,000 cases. Olmsted said the group has solved 90% of those cases — almost 70% were solved within the first seven days of starting work on them.

Although my personal experience of finding my biological family has been generally positive, I know that things don’t always turn out that way. When DNAngels reached out to Nancy, she was open to communicating and getting to know me — but there was no certainty that would be the result. I’ve read about the experiences of other adoptees helped by DNAngels whose biological families wanted nothing to do with them and the pain that caused.

When I told my parents I’d found my birth mother and had other siblings, they made it clear to me they wanted nothing to do with them — because this was my journey, not theirs.

For that reason and many others, Olmsted said having a support system in place before embarking on a journey like mine is important.

“Whether it be clergymen, or a spouse, or a family member or a best friend, someone needs to be there to support you through the journey,” she said. “You really need to have that support system in place before, during and after the process of identifying your biological truth.”

She said the journey adoptees go through has five phases: learning you’re adopted, the DNA testing/research phase, the identification phase, the reunion phase and, finally, the recovery phase.

“That’s the phase that you’re in right now, is the phase where you’re getting to know your biological mother, and you’re starting to heal some of those wounds that may have been created by the abandonment that you were even unaware of,” Olmsted said.

I’ve never had feelings of abandonment because I’d been put up for adoption — but I’ve read comments from others in my Facebook groups who do have those feelings and pain from it. I always felt if my biological parents didn’t want to raise me, I was better off with them giving me up for a family that did.

But being at peace with knowing I was given up at birth didn’t conflict with my desire to know where I came from. Fortunately, an organization like DNAngels exists to help people like me find answers.

“It’s a fundamental human right to know who your biological parents and ancestors are,” Olmsted said. “You don’t have a biological right to a relationship, but you have a right to the knowledge.”

Brian Bell is metro editor at the Orlando Sentinel. He can be reached at bbell@orlandosentinel.com.

____

©2024 Orlando Sentinel. Visit at orlandosentinel.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments