Inside the abrupt collapse of electric airplane startup Eviation

Published in Business News

The fall of zero-emissions electric airplane startup Eviation this month was triggered by a tense internal standoff among shareholders.

In mid-January, the company’s deep-pocketed, Singapore-based financial backer sent a letter to the shareholders that outlined a deep rift with the two Israeli co-founders and delivered a potent threat.

A representative of Clermont Group, the investment company of billionaire Richard Chandler that owns 70% of Arlington-based Eviation, wrote that Clermont would withhold further funding for 2025 unless the Israelis ceded control.

When the Israelis declined to step aside, Chandler abruptly pulled the plug. He stopped the monthly payments that kept Eviation running, prompting its collapse.

The board and management, led by CEO Andre Stein, had no option but to lay off most of the staff and pause all operations indefinitely.

The first and only flight at Moses Lake in Central Washington of Eviation’s 9-passenger electric airplane, which it called Alice, generated excitement in 2022. The company’s implosion is a blow to the state’s ambition to be a center for innovative, emissions-free green aviation technology.

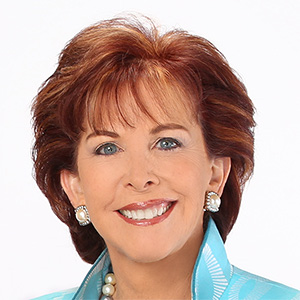

Aviv Tzidon, the Eviation co-founder and first chairman, who owns just less than 10% of the company, said in an interview Chandler’s ultimatum amounted to “if you don’t agree, nobody will have it.”

“He is willing to risk losing all the value” developed in Eviation since its inception in 2015, Tzidon said. “I do not understand it.”

In an emailed statement, Clermont spokesperson Michael Kearns wrote that the investment group still believes electric airplanes that take off and land conventionally “have a bright future” and that “Eviation management will continue to seek strategic, long-term partnerships to carry the programme forward.”

Despite being minority shareholders, the Israelis have broad veto power on Eviation’s strategy. The Clermont letter told shareholders this raised “serious governance issues that, left unaddressed, make the company unmanageable and uninvestable.”

However, Eviation’s second co-founder and first CEO, Omer Bar-Yohay, calls this “a manufactured crisis.”

In early February, he wrote to fellow shareholders that the alleged governance problems seem merely “a convenient excuse to shut the company down.”

Regarding Clermont seeking partnerships to revive Eviation, Bar-Yohay declared himself open to discussing any avenue that would “salvage the company or its assets” but wrote that “I’m still waiting for a real plan … to fix this self-inflicted mess.”

Tzidon and Bar-Yohay say they won’t simply give up the veto rights granted them in 2019 when Chandler first invested, giving them the power to block the strategic changes demanded by Clermont.

Eviation CEO Stein and Chief Financial Officer Jeff Hurford, both brought in as new leaders just over a year ago, did not respond to requests for an interview.

However, text messages that Tzidon shared with The Seattle Times show that, with the opposing shareholders deadlocked, management is “not sure how to continue.”

As time passes, with the engineers who were designing the electric airplane gone, the slim prospects for saving the project may dwindle to zero.

A house divided

Ironically, the shareholder letter, which was shared with The Seattle Times, began by noting Eviation’s progress in 2024.

Clermont Assistant General Counsel Leroy Langeveld wrote that during the year the company had stabilized the rate of cash burn and completed the conceptual design review of a new version of the Alice aircraft.

But the letter quickly moved on to Clermont’s problem with the two co-founders, citing the maxim that “a house divided against itself cannot stand.”

Tzidon and Bar-Yohay started Eviation 10 years ago in Israel and drew in Chandler as the major investor in early 2019.

The company’s U.S. design and production facility in Arlington remains a subsidiary of Eviation Aircraft Ltd. based in Israel, a detail that has become a key point of contention between the owners.

Chandler’s 70% ownership stake is in that Israeli parent company.

In bringing Chandler in, the two Israeli co-founders insisted on retaining some control by holding veto power over major changes to Eviation’s mission or the proposed aircraft’s development. They also have a say in nomination of board members and the board chair.

According to Clermont, this has resulted in “being unable to confirm supplier selection … the board not supporting management decisions and … delayed decision making.”

“The lack of cohesion and cooperation among board members has become a significant impediment to our operations,” Langeveld wrote.

He then laid out Clermont’s demands:

—Eviation’s parent company must relocate from Israel to the U.S.

—The chairman of the board must be appointed by a majority vote.

—The board must support management recommendations on suppliers.

—“Amend the constitution to remove the founder veto.”

These demands were declared “essential,” with future funding at stake without a positive response by the time of the next board meeting, just a week later.

An impasse with the founders

Tzidon said he’s unwilling to simply cede his rights and blames Clermont for the lack of progress since that 2022 first flight.

“We have a flying aircraft, and it’s not flying. We talk to investors, and nobody invests. We talk to partners, and we don’t have any partner. And now we don’t have this team that brought this aircraft to the air,” he said. “Value has been destroyed.”

Bar-Yohay told fellow shareholders in his letter that “Clermont, as the majority shareholder, controlled every decision.”

He wrote that he never once exercised his veto right. “It is Clermont’s leadership that brought us here.”

Clermont’s mention of opposition to supplier decisions is a reference to another company in the Clermont Group: Everett-based electric motor company MagniX.

Clermont from the onset in 2019 wanted Alice powered by motors from MagniX, which started in Australia before Clermont moved its headquarters to the U.S., first to Redmond and then to Everett, led then by Roei Ganzarski, a former Boeing executive.

Tzidon said the insistence on using the motors from the Clermont sister company were “to the benefit of MagniX,” not Eviation.

The MagniX motors that powered the first flight of Alice were heavier than alternatives, Tzidon said, and required changes to the airframe design that he considered negative.

“If Eviation could have been sovereign to do what it wants, it will not buy motors from MagniX,” he said.

Tzidon expressed other differences with Clermont’s running of Eviation.

He opposed appointing a chairman he saw as “a bean counter,” but otherwise he said he did not exercise his veto.

For the U.S. operation, he had preferred a site Eviation had already established in Prescott, Ariz., near the western campus of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. But he said he didn’t block Clermont instead setting up in Arlington.

However he sees potential legal barriers to Clermont’s demand to move the parent company from Israel.

He said much of Eviation’s original intellectual property “was subsidized and supported by funds from the taxpayer in Israel” and cannot be simply moved.

“Everything is owned by the Israeli entity,” he said. “You create a daughter company and you close the mother company, you can’t do it. This is illegal.”

Can Eviation be revived?

Eviation’s Alice uses regular airports and, to be certified, must meet existing aviation regulations. Though a new technology, it has a more direct path to market than say the many vertical takeoff and landing air taxis under development.

In its emailed statement, Clermont said “we believe Eviation has played an important role in advancing electric aviation and demonstrating the commercial market” and that it is still seeking a way forward.

The company has a design that can fly and at least loose order agreements with a variety of small commuter airlines — including New England-based Cape Air and flyVbird of Germany — that Eviation claims are worth $5 billion if they can be converted into aircraft deliveries.

But certifying the airplane’s design, bringing it into production, and entering passenger service, previously planned for 2027, will require more heavy investment. And the once-hot venture capital interest in green aviation has cooled.

A person familiar with how Clermont views the situation, who asked not to be identified to speak freely, said the investment group still believes in green aviation.

Clermont is still funding MagniX, which is developing motors, powertrains and batteries for electric aircraft.

For Eviation, it acknowledges the project will take more time and is focused on seeking new investment, the person said.

Bar-Yohay is pessimistic. He said that while Eviation has moved the needle on what’s possible for electric aviation, it will be difficult to raise the level of additional capital needed to revive the company.

Tzidon is more sanguine. In a letter to the other shareholders this week he wrote “Our top priority is to ensure that Alice has the best possible trajectory, which involves identifying and engaging with potential partners.”

For now though, the shareholders remain deeply split, dimming the prospect of any resurrection.

©2025 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments