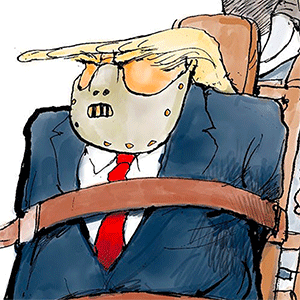

Rubio's ascendance masks bigger question of who has Trump's ear

Published in Political News

A jolt of staff upheaval this week made Marco Rubio the first person in 50 years to hold the top two national security jobs in the U.S. government, the culmination of a journey from his role as Donald Trump’s rival for the presidency to one of his most prominent aides.

Rubio’s ascent to both secretary of state and interim national security adviser coincided with the fall of Mike Waltz, whose hawkish foreign policy stances made Trump’s MAGA base wary. Waltz was ousted from his West Wing job after inadvertently including a journalist on a Signal group chat about military actions and will be nominated to be Trump’s ambassador to the United Nations.

On the surface, the upheaval highlights the former Florida senator’s deft navigation around concerns about his late-to-hatch Trump-world bona fides and his emergence as an impassioned messenger for the president.

Yet the question of who won or lost Trump’s favor masks a reality for both men: neither Rubio nor Waltz has taken the lead on some of the foreign policy issues most important to the president, and their influence has never been truly tested.

Despite being the top U.S. diplomat, Rubio takes a back seat on ending the Ukraine war and confronting Iran’s nuclear program to Steve Witkoff, the longtime Trump friend and real estate developer. In Africa, Trump has named his daughter Tiffany’s father-in-law, Massad Boulos, to oversee talks related to the Democratic Republic of Congo and other matters.

Rubio’s rival for the secretary of state job, special envoy Richard Grenell, has run negotiations with Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, at times clashing with Rubio.

That doesn’t even count all the others who have Trump’s ear, including Elon Musk, who dismantled the U.S. Agency for International Development and other government agencies; Trump’s son Donald Jr.; TV personality Tucker Carlson; and far-right activist Laura Loomer, who took credit for an earlier staff purge at the National Security Council.

“It is a larger presence for Rubio — what he can make of that remains to be seen,” said Justin Logan, director of defense and foreign policy studies at the libertarian-leaning Cato Institute. “The national security adviser always is important because of its proximity to the president,” but may be less so in this White House “because power in this administration is highly centralized under one person.”

Rubio’s actions in the next few weeks will help clarify how much his expanded portfolio adds to his leverage. It won’t be easy given that the White House has yet to appoint or nominate staff for numerous senior roles at both the State Department and the National Security Council.

Rubio may not hold both jobs for long. The last person to do so was Henry Kissinger in the 1970s. The White House is considering permanent replacements for Waltz. Candidates include Grenell, White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller and Sebastian Gorka.

“The president has assembled a world-class team that works together to implement the policies he sets,” a State Department official said Saturday, speaking on condition of anonymity. “There no egos and everyone is rowing in the same direction.”

While Waltz’s departure gives more power to Rubio, it also leaves Rubio without an ally in Washington on several issues. He and Waltz were aligned on many of their publicly stated policy positions, with a traditionally conservative bent that tracks with decades of Republican policy convention. That’s out of step with MAGA supporters such as Vice President JD Vance, Carlson and other members of the administration.

On questions like Iran, “Will Rubio seek to influence that sort of decision tree?” Logan said. “I have to imagine he will, but if he sees himself getting crosswise with the president, will he pull back or push forward? That’s a question for Marco Rubio.”

Rubio’s rise is one of the more surprising turnarounds of Trump’s second term as he has shed many previously held views — on Russian President Vladimir Putin, NATO, the value of the USAID — to adopt a far more strident tone that appeals to the president’s base.

He batted away concerns around the dismantling of USAID and shut down reporters who criticized the move to revoke visas for dozens of international students studying in the U.S. And he’s been a vocal defender of Trump’s move to deport Kilmar Armando Abrego Garcia, the Maryland resident mistakenly deported to an El Salvador prison.

Hours after his appointment as interim national security adviser, Rubio went on Fox News for an interview with Sean Hannity, riffing on a joke Vance had made earlier in the day that Rubio might get selected as the next pope, given the speed of his ascent. And he gave credit to Trump for the first 100 days of foreign policy.

“The question here is, who’s the only leader in the world that can talk to both sides and hopefully bring them to a deal?” he said of the war between Russia and Ukraine. “And that’s President Trump.”

The comments were only remarkable in the current White House because of who said them. As a senator who had sought the Republican nomination against Trump in 2016, Rubio hammered former Exxon Mobil Corp. Chief Executive Rex Tillerson — Trump’s first nominee to be secretary of state — for refusing to call Putin a war criminal. He praised USAID and many programs now being dismantled at the State Department.

“He was a stalwart opponent of authoritarian governments and critic of Vladimir Putin,” said Kori Schake, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, who served in the George W. Bush administration. “And none of those seem to be either choices of the administration or attitudes that the secretary of state continues to hold.”

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments