The US has pardoned insurrectionists twice before – and both times, years of violent racism followed

Published in Political News

Donald Trump is the third U.S. president to pardon a large group of insurrectionists. His clemency toward those convicted of crimes related to the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection – including seditious conspiracy and assaults on police officers – was different in key ways from the two previous efforts, by Andrew Johnson in 1868 and Ulysses S. Grant in 1873.

But they share the apparent hope that their pardons would herald periods of national harmony. As historians of the period after the Civil War, we know that for Johnson and Grant, that’s not what happened.

When Johnson became president in 1865 after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, he faced a combative Congress. Though Johnson had opposed the secession of the Southern states before the Civil War began, he agreed with former Confederate leaders that formerly enslaved people did not deserve equality with white people.

Further, as a Southerner, he wanted to maintain the social conventions and economic structure of the South by replacing enslavement with economic bondage. This economic bondage, called sharecropping, was a system by which tenant farmers rented land from large landowners. Tenants rarely cleared enough to pay their costs and fell into debt. In effect, Johnson sought to restore the nation to how it was before the Civil War, though without legalized slavery – and sought every avenue available to thwart the plans of the Radical Republicans who controlled both houses of Congress to create full racial equality.

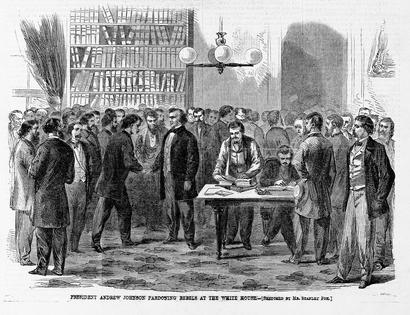

Johnson signed an amnesty that gave a blanket pardon to all former Confederate soldiers. However, he required formerly high-ranking Confederate officials to individually seek pardons for their involvement in the rebellion. These officials faced permanent disfranchisement and could not hold federal office if they did not seek a pardon.

When Congress was in recess, Johnson vetoed two bills that had been passed: one to help find homes for formerly enslaved people who could no longer live on the property of their enslavers, and the other to define U.S. citizenship and ensure equal protection of the laws for Black people as well as white people.

Johnson also told Southern states not to ratify the 14th Amendment, whose purpose was to enshrine both citizenship and equal protection in the Constitution.

When Congress came back in session, it continued its effort of Reconstruction of the former Confederate states – reforming their racist laws and policies to comport with the liberty and equality the Union was committed to – by overriding Johnson’s vetoes and requiring former Confederate states to ratify the 14th Amendment as a condition of readmission to the Union. But Congress could not override the pardons the president had granted.

This continued political warfare resulted in Johnson being impeached – but not convicted or removed from office. But the back-and-forth also stalled Reconstruction and efforts toward racial equality, ultimately dooming the effort.

Nathan Bedford Forrest was not covered by Johnson’s general amnesty. As a former Confederate general, he had to apply for a personal presidential pardon, which Johnson granted on July 17, 1868. Two months later, Forrest represented Tennessee at the Democratic Party’s national convention in New York City.

He also took command of the Ku Klux Klan, the unofficial militant wing of the Democratic Party. Forrest initiated the title “Grand Wizard,” a bizarre title derived from his Civil War nickname, “Wizard of the Saddle.” He became a leader of former Confederates who resisted Reconstruction through violence and terror.

After his pardon, Forrest perfected a rhetorical technique for his extremism. His biographer Court Carney described it as a multistep process, starting with, “Say something exaggerated and inflammatory that plays well with supporters.” Then, deny saying it “to maintain a semblance of professional decorum.” Then, blur the threats with “crowd pleasing humor.” It proved an effective way of threatening violence while being able to deny responsibility for any violence that occurred.

Under Forrest’s leadership, membership in the violent, racist Ku Klux Klan spread almost everywhere in the South. Records are sketchy, so it’s impossible to say how many people were lynched, but the Equal Justice Initiative has documented 2,000 lynchings of Black Americans during Reconstruction. Black women and girls were often raped by klansmen or members of its successor militias.

It’s also not possible to say how many pardoned ex-Confederates participated in the lynchings. But the violence was so widespread that just about everyone, North and South, thought the political violence was a resumption of the Civil War.

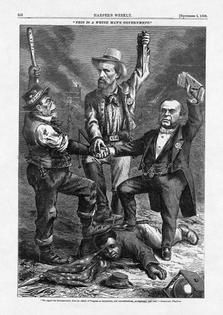

In the Piedmont of the Carolinas, klan violence amounted to a shadow government of white nationalists. Grant ordered the U.S. Army to apprehend the klansmen, and a newly minted Department of Justice prosecuted the insurrectionists for violating civil rights guaranteed by the 14th and 15th amendments. After several trials that proved to be what the federal judiciary’s official history calls “dramatic spectacles,” federal judges handed down conviction after conviction.

The federal government’s decisive action allowed for a relatively free presidential election in 1872. Black voters helped Grant win in eight Southern states, contributing to his landslide victory.

But after his reelection, Grant appointed a new attorney general, who dropped the pending klan cases. Grant also pardoned klansmen who had already been convicted of crimes.

Grant hoped his gesture would encourage Southerners to accept the nation’s new birth of freedom.

It didn’t. The pardons told former Confederates that they were winning.

John Christopher Winsmith, an ex-Confederate who embraced racial equality and whose father had been killed by the KKK, wrote to Grant in 1873, “A few trials and convictions in the U.S. Courts, and then the pardoning of the criminals” had emboldened what he called “the hideous monster – Ku Kluxism.”

And a new gang arose, too: the Red Shirts, who began to murder Black people openly, not even in secret as the klan did. Two of the Red Shirts were later elected to the U.S. Senate.

Paramilitary groups established anti-democratic one-party rule in every former Confederate state, imposing discriminatory laws known as Jim Crow, which were enforced by lynchings and other forms of racial violence.

The federal government took no substantive action against this for a century, until the 20th century’s Civil Rights Movement sparked change. And it wasn’t until 2022 that Congress passed an anti-lynching bill.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Joseph Patrick Kelly, College of Charleston and David Cason, University of North Dakota

Read more:

60 years of progress in expanding rights is being rolled back by Trump − a pattern that’s all too familiar in US history

The Confederate battle flag, which rioters flew inside the US Capitol, has long been a symbol of white insurrection

What everyone should know about Reconstruction 150 years after the 15th Amendment’s ratification

I was for several years a volunteer with the Charleston County (SC) Democratic Party.

David Cason does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments