Medicaid overhaul proves to be politically perilous proposition

Published in Political News

WASHINGTON — In their quest to pay for President Donald Trump’s policy priorities, Republicans are eyeing Medicaid, the largest health insurance program for more than 70 million low-income Americans, as a program ripe for cuts. But they face obstacles that could block any sort of overhaul to the nearly 60-year-old joint state and federal program.

Among those obstacles: public opinion, members of their own party in competitive districts, governors who worry about impacts to their state budgets, a closely divided Senate, and maybe one of the most formidable: hospitals and health care providers that carry significant influence in Washington.

While House Republicans and some governors are coalescing around “work requirements” in Medicaid as a way to save money, more significant cuts — and more politically perilous ones — remain on the table.

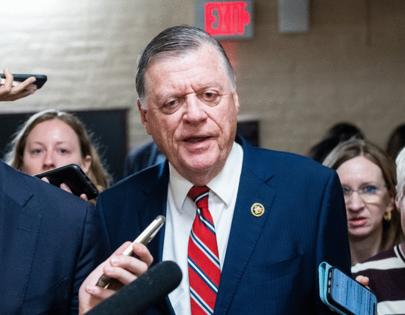

“That’s the one mandatory program that really is open to serious reform,” said Rep. Tom Cole, R-Okla., chairman of the House Appropriations Committee.

The federal government spent $618 billion on Medicaid in fiscal 2024, making it the largest stream of funding from the federal government to states.

“It’s pretty natural that Medicaid would get a lot of scrutiny because there’s a lot of savings,” Cole said.

But it also makes significant changes very difficult. States already face Medicaid funding challenges, with rising prescription drug costs and the growing cost of medical care.

Medicaid also continues to enjoy broad support from the public, and Democrats indicate they will hit Republicans on “cuts” in the midterms should Republican succeed in their efforts.

‘Existential threat’

And hospital associations and hospitals in members’ districts for weeks have quietly been pushing back against Medicaid reductions.

“Hospitals are really viewing this as an existential threat,” said Carlos Jackson, a principal at Cornerstone Government Affairs, especially proposals to lower the federal government’s share of Medicaid expansion funding and limiting state-directed payments to hospitals.

In general, any reduction in Medicaid funding to states would force states to cut services, reduce rates, limit benefits or find the money elsewhere.

That will be a hard sell to hospitals — Medicaid payments account for about 19% of all payments to hospitals in 2022.

And in rural states and states that expanded Medicaid under the 2010 health care law, that percentage is even higher; in Alaska, Medicaid makes up about 30% of hospitals’ revenue, according to an analysis by Definitive Healthcare.

The complicated dynamic was acknowledged by House Energy and Commerce Chair Brett Guthrie, R-Ky., in an interview this week.

“They’re [hospitals] operating within the current system, and anytime you change the system, then they obviously get concerned,” Guthrie said.

Guthrie has said the committee is looking at various Medicaid savings options, including capping what Medicaid spends per beneficiary while allowing for growth for medical inflation; work requirements for some adults; and changing the federal government’s share of Medicaid spending for the population of adults who received coverage under the 2010 health care law’s eligibility expansion.

“If you’re a provider you want that growth, but it’s just not sustainable and we can’t afford it,” Guthrie said.

The proposals have caused tension in the House Republican Conference, with more moderate members warning against deep Medicaid cuts that could have significant impacts on their states’ budgets and their constituents, including politically powerful hospitals.

It’s a tension Trump appeared to acknowledge last month, when he said Republicans will “love and cherish” Medicaid, Medicare and Social Security.

“We’re not going to do anything with that, unless we can find some abuse or waste,” Trump said last month to press in the Oval Office. “The people won’t be affected. It will only be more effective and better.”

Still, Republicans argue that many of the proposals they’re discussing aren’t really “cuts,” though experts say they would have downstream effects that could result in less funding to states, which could lead to service cuts for patients and rate cuts to providers.

Speaker Mike Johnson, R-La., has said no “benefit-related reforms” would be made to Medicaid. But that still leaves on the table a whole host of options members have talked about for months.

“If you eliminate fraud, waste and abuse in Medicaid, you’ve got a huge amount of money that you can spend on real priorities for the country,” Johnson said Tuesday.

House Republican leaders want to find $1.5 trillion 10-year spending cuts to help pay for a $4.5 trillion tax cut package.

The House Budget Committee is scheduled to mark up a budget resolution Thursday that would direct Energy and Commerce, which has jurisdiction over Medicaid, to find at least $880 billion in savings.

In total, the changes could reduce federal Medicaid spending by hundreds of billions of dollars, according to a document from the House Budget Committee, although much of that cost would be shifted to states.

Senate Republicans, who are working on their own version of a reconciliation bill, want to give instructions to committees to save billions of dollars to pay for border security, defense spending and more by March 7.

The Senate Finance Committee, which has jurisdiction over Medicaid, would need to find savings to reduce the deficit by at least $1 billion. On Wednesday, Finance Chairman Michael D. Crapo, R-Idaho, said his committee would seek savings by repealing a Biden administration rule establishing minimum requirements for nursing home staffing, rather than cutting Medicaid.

But Senate Republicans also want to do a second reconciliation package later in the year, and have not said what role Medicaid will play in that bill.

“While some have suggested dramatic reductions in the Medicaid program as part of a reconciliation vehicle, we would urge Congress to reject that approach,” American Hospital Association President and CEO Rick Pollack said in a statement Wednesday. “Medicaid provides health care to many of our most vulnerable populations, including pregnant women, children, the elderly, disabled and many of our working class.”

Medicaid expansion

One of the most impactful policies would be reducing how much the federal government spends to cover the Medicaid expansion population.

The 2010 health care law allowed states to expand Medicaid to adults earning up to 138% of the federal poverty line: about $21,000 a year for an individual. It has been a huge boon for hospitals, with research showing it helped reduce closures and improved access to care.

The federal government pays for 90% of the cost for the 41 states — including Washington, D.C. — that have expanded Medicaid to cover that population; that’s about 20 million people as of 2024, according to KFF, a health policy research organization.

For the traditional Medicaid population, the federal government pays between 50% and 74% of costs, depending on the state.

The higher rate for expansion states was intended to incentivize states to expand Medicaid. But Republicans, who have long opposed the 2010 health care law and tried to repeal it in 2017, say it is unfair.

“We need to get our handle around this expansion population,” Guthrie said this week, arguing it is “unfair” that Medicaid spends more on what he described as “healthy” adults than on disabled children and other traditional beneficiaries. “How do we do that in a way that makes it sustainable, states can afford it, and we get fairness in Medicaid?”

Reducing the federal government’s expansion contributions would have an immediate impact. Nine states, including North Carolina, Arkansas and Virginia, have laws that would end Medicaid expansion if the federal government’s share drops below current levels.

“These provisions could result in cuts to benefits, programs, or provider reimbursement in a way that would be detrimental to the people that receive these lifesaving services,” said Summer Tonizzo, a spokesperson for the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services.

Governors and hospitals were key stakeholders that sought to stop Republicans from passing a 2017 bill that would repeal the 2010 health care law, including the Medicaid expansion, and turn Medicaid into a block grant to states rather than an open-ended entitlement that grows with enrollment.

Work requirements

Some governors and stakeholders have shown more willingness to support a work requirement.

The Congressional Budget Office has found work requirements would save the federal government $109 billion over a 10-year period while doing little to increase employment.

Experts say that’s because most Medicaid beneficiaries already work and similar efforts in Arkansas in 2017 saw 18,000 people lose coverage, mainly because of failure to comply with administrative hurdles or red tape, even if they would qualify for exemptions.

Under a 2023 Republican bill that would institute Medicaid work requirements, the CBO found 600,000 people could become uninsured.

Hospitals don’t like work requirements, but might be willing to accept them if that meant other policies more damaging to their bottom lines were avoided, said one hospital industry lobbyist, who declined to be named in order to speak candidly.

And several states with Republican governors have already indicated they will pursue work requirements, including Ohio, Arkansas and South Carolina.

Such requirements are a “low-hanging fruit” for Republicans, the lobbyist said.

©2025 CQ-Roll Call, Inc., All Rights Reserved. Visit cqrollcall.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments