Commentary: The constitutional crisis is real

Published in Op Eds

Is the U.S. facing a constitutional crisis? The answer, unequivocally and emphatically, is yes. But it also could get much worse.

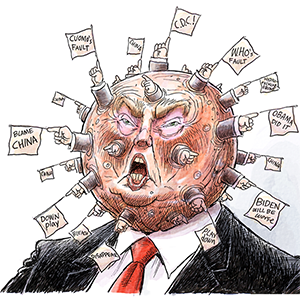

In less than 100 days, President Donald Trump has taken an astounding array of unconstitutional actions to consolidate power and to stifle dissent. He has asserted the ability to eliminate federal agencies created by statute and to refuse to spend federal funds allocated by federal law. He has claimed the power to fire anyone who works in the executive branch, notwithstanding federal laws limiting removal. He has attempted to override the Constitution by eliminating birthright citizenship. He has withheld money from universities without following procedures mandated by law and without legal justification. He has violated the 1st Amendment by revoking visas solely because of the views the visa holders expressed.

These illegal acts don’t just harm the individuals on the receiving end; they harm us all. Significant layoffs in the Social Security Administration will mean many people who are eligible for benefits won’t get them, at least not in a timely manner. Cutting off funds for international aid will cause people in other countries to die from lack of medical care and food. Cuts in medical, scientific and university research will reverberate for years, with devastating consequences for basic science, innovation and finding cures for diseases.

But of all Trump’s illegal executive orders and other actions, none is more inimical to our Constitution and the republic than its claim that it has the power to put human beings in a maximum-security prison in El Salvador with no court in the United States having the power to provide recourse. The president has clearly said this could include U.S. citizens and not just the immigrants he has subjected to extrajudicial “disappearance” so far.

To be clear, the government has no authority to put anyone, noncitizens or citizens, in a maximum-security prison in El Salvador. And it has no authority to imprison anyone period, or to deport them, without due process. The federal courts must have the power to stop illegal incarceration and to ensure the return of anyone illegally imprisoned in order that due process can occur. Otherwise, we exist under a dictatorship, not a democracy under the rule of law.

That is why two matters now pending in the federal courts are so important. It is not hyperbole to say that the future of our constitutional democracy may turn on these cases.

One involves the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, which the administration has invoked to send alleged members of a Venezuelan gang to a maximum-security prison in El Salvador. This is blatantly illegal. The Alien Enemies Act allows the government to deport males over the age of 14 from an enemy nation when the United States is in a declared war or there is an imminent military invasion. It has been invoked just three times since it was passed in the 18th century: during the War of 1812, World War I and World War II. It has no application to today’s situation, and even if it did, it does not authorize incarceration in a foreign prison.

On the day this began, Judge James Boasberg, of the U. S. District Court for the District of Columbia, held an emergency hearing and told the administration to pause the removals and ordered the return of the deportation flights back to the United States. The government did not follow the order. This week, Boasberg indicated that the government was likely in contempt of court, that the government’s refusal to halt the flights demonstrated “willful disregard” of the court “sufficient” that there was probable cause “to find the Government in criminal contempt.” This follows from many Supreme Court decisions that the rule of law requires that court orders be complied with until and unless they are vacated or overturned on appeal. It is unclear as to whether this contempt finding will have any effect.

The other matter now pending in the courts involves Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a lawful resident of the United States, whom a government attorney admitted to the court was apprehended by mistake and wrongfully included in the shipment of supposed gang-member immigrants to the El Salvador prison.

The federal district court in Maryland ordered the government to “facilitate and effectuate” his return to the United States. The government refused and appealed to the Supreme Court. On April 10, the justices sent the case back to the district court saying the lower court had the authority to require the government to “facilitate” Abrego Garcia’s release from custody in El Salvador, but they also said it was unclear whether the district court has the power to “effectuate” this.

The Trump administration has used the ambiguity in the court’s order to justify doing nothing for Abrego Garcia and nothing to remedy its own error and illegal actions.

Anyone who studies the law or high school civics understands that the Trump administration cannot be right in its treatment of Abrego Garcia or in its position that the courts can have no say in the matter. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in her dissent in the case involving the Venezuelans, the history of lawless regimes that deny due process is well known, “but this nation’s system of law is designed to prevent, not enable, their rise.”

Until now, I did not appreciate how much our constitutional democracy depends on the good faith of those who govern us to comply with the law, including court orders. Are there sufficient guardrails to protect us when an administration will not comply? Will we continue to be a nation under the rule of law?

We shall see.

____

Erwin Chemerinsky, a contributing writer to Opinion Voices, is dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law.

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments