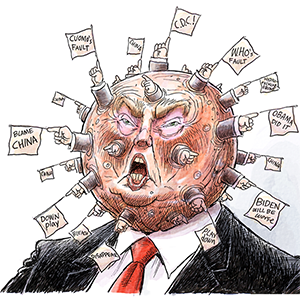

Trump and his lawyers think he can get away with anything. It's outlandish.

WASHINGTON -- "The king can do no wrong." That is the ancient legal maxim used to explain why a sovereign should not be held to account for misdeeds. President Trump and his lawyers are now making arguments that make this legal doctrine look wimpy. Their vision boils down to: The king can do whatever wrong he damn pleases, and there's nothing you can do about it.

This approach, aggressive to the point of outlandish, was on florid display in a federal appeals court in New York this week, as the president's private lawyer asserted that, yes, Trump could actually shoot someone in the middle of Fifth Avenue with impunity so long as he is president.

This might sound like a catchy restatement of the generally accepted, although constitutionally untested, wisdom that a sitting president cannot be indicted. But it is actually much worse. Trump lawyer William Consovoy was not only asserting that the president is immune from being criminally charged while in office. He was claiming that the president cannot even be investigated.

To understand the radical nature of this claim, consider the setting in which it arose. Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance is seeking documents -- not testimony, just information, including eight years of Trump's tax returns. He is seeking them not from Trump himself but from his accounting firm. They would be protected from disclosure by grand jury secrecy. Apparently, however, the king's business can do no wrong either.

Second, consider the difference between Consovoy's assertion and the approach taken by former special counsel Robert Mueller. Complying with Justice Department policy, Mueller accepted that Trump couldn't be indicted. But Mueller explained that not only was it permissible to conduct an investigation while Trump was in office, it was important in order to collect evidence while it was still fresh. Indeed, the very Justice Department memo on which Mueller relied made clear that a "grand jury could continue to gather evidence throughout the period of [presidential] immunity."

Now comes Consovoy, a former clerk to Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, to claim that the powers of the presidency cannot tolerate Vance's attempted intrusion. This is an astonishing departure from settled law. In U.S. v. Nixon in 1974, a unanimous Supreme Court upheld a subpoena for tapes of the president's private conversations while in office, rejecting "an absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances." Vance's subpoena, by contrast, calls only for Trump's private records; it would not chill his ability to receive candid advice from aides.

In 1997, again unanimously, the court ruled that another sitting president, Bill Clinton, could be sued for sexual harassment in federal court. Although the decision did not address the question of state lawsuits, it is hard to imagine how a civil lawsuit could be allowed while a grand-jury subpoena for his records would go too far. Which is a greater distraction for a sitting president?

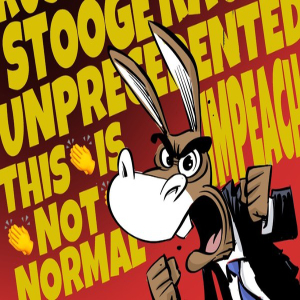

The dangerous audacity of Trump's position becomes clear: Whatever information his adversaries are seeking, whether in a lawsuit or a congressional inquiry, they can't have it. And he is making the claim everywhere:

-- Trump's private lawyers, backed by the Justice Department, have argued that the House Oversight Committee has no right to obtain records from Trump's accounting firm because its investigation serves "no legitimate legislative purpose" -- that is, the records are not being sought as part of an impeachment inquiry. This month, the federal appeals court in Washington rejected this contention.

-- Meanwhile, the Justice Department went to court rather than comply with the House Judiciary Committee's request for grand-jury materials from the Mueller probe, saying that a federal judge was wrong in 1974 in providing Congress materials from the Watergate grand jury. "Wow, OK," observed Chief U.S. District Judge Beryl Howell. "The department is taking extraordinary positions in this case."

-- Finally, the White House summarily announced, in a letter from White House counsel Pat Cipollone to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, that it would not comply with an impeachment proceeding it termed "constitutionally invalid and a violation of due process." Cipollone complained that the House had not voted to authorize an impeachment inquiry -- no matter that the text of the Constitution mandates no such vote.

To sum up: The king can't be investigated by law enforcement -- nor can the information that law enforcement has gathered about him be turned over to Congress. He can't be required to disclose evidence to lawmakers conducting oversight because they aren't impeaching him -- but he won't cooperate with an impeachment inquiry unless the processes comply with his dictates.

L'etat c'est Trump. It will be up to the courts, ultimately the Supreme Court, to tell him otherwise.

========

Ruth Marcus' email address is ruthmarcus@washpost.com.

(c) 2019, Washington Post Writers Group

Comments