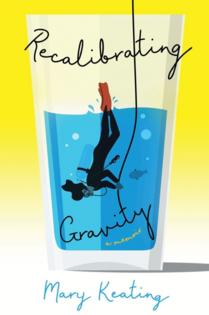

Disability memoir explores life, love and human experience through poetry

Published in Mom's Advice

It’s been said before that most poetry is autobiographical. Poetry is known to draw from a place of truth — whether emotional truth, universal observation, or personal anecdote. But "Recalibrating Gravity" by Mary Keating is a true memoir, told through a series of poems. In many ways, verse is the ideal form for Keating to share a story that demands to be heard. Told through multiple vignettes the story is written in a way to convey feelings without directly spelling it all out for the reader, something a memoir in prose might be more inclined to do. Keating doesn’t have to tell readers how she feels — the poems speak for themselves.

The arc of the poet’s life is glimpsed in the Table of Contents, beginning after the preface with “The Making of a New Year’s Baby” and ending with “The Journey Home." But it takes diving in fully to know Mary Keating’s true story.

At age 15, in a Mustang driven by “a boy trying too hard to be cool”, Keating’s life changed. The car wrapped around two oaks, and left her paralyzed, numb from the chest down, with a permanent new accessory: a wheelchair. The pain and fear in the accident’s aftermath are laid bare in part two, from the hospital to rehab, detailing the way Keating must recalibrate her body and mind to get used to life as a paraplegic.

From the inaccessibility and discrimination that is all too common in hospitals, schools and workplaces, to the unkindness of strangers, to an eventual cancer diagnosis, "Recalibrating Gravity" tackles the toughest moments of Keating’s life. The details of her accomplishments, laid out in “Passing Time,” brighten the pages. “Graduating law school/ Falling in love/ Passing the bar./ Learning to scuba/ Getting married/ Cheating cancer.”

While diagnoses, life-changing paralysis and a complete shift in life’s trajectory are shocking for a 15-year-old to have to cope with, much of Keating’s anger and frustration throughout the next several decades of her life lies with the systems and doctors that fail to help people with disabilities. So much institutionalized ableism and ignorance is commonplace and serves as a constant obstacle for Keating and other disabled people living in a world that was not built with disability in mind.

For strength and for guidance, Keating turns to her faith in God, a feminine divine power referred to as “Her”; this is paralleled by her reliance on her mother, who was a complex but courageous and defining force throughout her life.

"Recalibrating Gravity" is filled with just under 100 poems. Throughout, Keating plays with form, rhyme scheme and repetition, though she reliably returns to free verse. There’s a rhythm and cadence that begs for several poems to be read aloud.

In “Bungaroosh”:

“Wonder if I would tap my ruby slippers too readily/ when the sky switches melody — resonates me/ with the melancholy of something waiting to be lost”

Or this rhyming section on the shortcomings of life-saving technology, from “Lost Humanity in Wheelchair Dis-Repair”:

“But beware if those lights stop blinking/ A sign technology’s not linking/ Nothing revives the power that’s died/ Not a tap or twirl or whack on the side”

Though Keating’s individual experiences may not be relatable for all — because her life’s experience is just that, her own— she deploys universal truths and emotions that anyone can connect with, disabled or not. Her story of struggle and frustration, of triumph and acceptance is touching, an effect that any great poetry collection shares. Part disability memoir, part poetic meditation on the universal challenges of being human, Mary Keating has bared all in this lyrical and moving collection.

Comments