'Breakfast Club' is reuniting at C2E2. What do Gen Zers at John Hughes' school think of the Gen X movie?

Published in Entertainment News

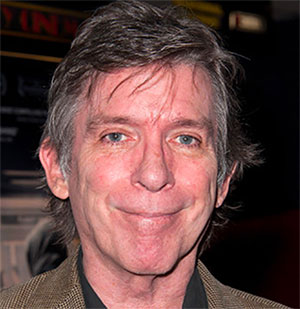

CHICAGO — On Saturday morning, exactly 40 years after they first met in Saturday morning detention, every member of the original Breakfast Club — the popular girl (Molly Ringwald), the jock (Emilio Estevez), the recluse (Ally Sheedy), the nerd (Anthony Michael Hall), the rebel (Judd Nelson) — will reunite, for the first time since 1985. The occasion is C2E2, the annual Chicago Comic and Entertainment Expo at McCormick Place. But here’s the thing about high-school reunions:

Nothing changes.

Even when everything about your old high school changes.

As in, transforms so radically in five decades that a student there now would have trouble relating to a student there 40 years ago. A couple of days before the Breakfast Club was set to visit the South Loop, I met with six teenagers at Glenbrook North High School to watch “The Breakfast Club” itself. Most had never seen it. But all were well aware of its outsized legacy in the long hallways of this sleek 72-year-old North Shore institution: John Hughes, the film’s director and writer, a man who arguably helped shape the way we think about teenagers, based the movie on his own experiences as a student at Glenbrook North. He didn’t shoot there; the set was Maine North High School in Des Plaines, which had closed a few years before filming, partly because of declining enrollment. Baby boomers built too many schools, then didn’t make enough Gen Xers.

That’s ancient history to Gen Zers.

Within 10 minutes of clicking the play button, I felt like I was introducing these six students to a great new revolutionary invention called the cotton gin. Judd Nelson threw one of his many tantrums in the film: Avery DiCocco, chipper, vice president of the student association, a senior, with a scrutinizing expression, shook her head and said, “I mean, that would be all over Snapchat.” The others nodded. When the school’s vice principal took a sip from a water fountain, DiCocco pounced: “Nope! We carry water bottles — nobody drinks directly out of the fountains.”

They were warming to time travel.

There’s a scene where Judd Nelson is locked in a closet by the principal. Asher Panfil, senior, a sports guy, seated in an egg chair, said to the screen: “If that happened in Northbrook, his parents would sue so fast.” Beside him, Drew Horvath, another sports guy, said: “ So fast.” Beside them, senior Kady Serlin, aspiring filmmaker: “What if there was a fire? That’s a liability issue.”

Samantha Katz, senior, in a baggy gray sweatshirt, craned her head back: “It’s pretty hard to even get detention in this school now.” Lincoln Brown, junior, in a green hoodie, added wryly: “There are rumors …” Katz looked to assistant principal Michael Tarjan seated nearby: “Do we even still do a Saturday morning detention?” Actually, they do; there’s one thing that hasn’t changed. But none of them have ever done anything bad enough to warrant such a sentence.

“I’ve actually heard everyone in Saturday detention are friends,” said Horvath, waving at another scene in which the Breakfast Club are bickering strangers, not yet knowable to one another. “I’ve heard they get like an hour for lunch, they get to leave 15 minutes early and it’s not even strict.”

On screen, the vice principal (played by character actor Paul Gleason) was threatening someone again; he’s always threatening someone or shoving. The real students cringed every time. “No,” said Serlin, “you’re not allowed to threaten students.” Panfil, who has practice for one sport or another nearly every morning, said, “I don’t know the last time I had a free Saturday morning.”

“The Breakfast Club,” a film that felt so immediate and revealing if you were a certain age in 1985, is now, in 2025, a clearing house of the unthinkable, the expired and probably litigious.

As they watched, the students cataloged what had changed in 40 years: They don’t use lockers anymore (even though old lockers still line many Glenbrook hallways); they prefer backpacks. And they certainly don’t write gay slurs in huge letters down the front of those lockers, as in the film: “We’d get an email about that,” Horvath said, with a deadpan understatement. The books and magazines in the film’s library? They rarely check out books on their own and never read magazines. Also, nobody smokes cigarettes anymore; school bathrooms are installed with silent alarms in case of vaping. When Molly Ringwald was dropped off by her father in a BMW, they noted some students here drive BMWs themselves; the parking lot has seen its share of Teslas, too. Glenbrook North, which serves Northbrook, is in one of the richest ZIP codes in the state.

As for those clothes … They definitely would not be putting so much work into a Saturday morning wardrobe. (More than a few students here wear pajamas to class, a nearby adult whispered.)

Still, Ringwald, prim, poised, in long leather boots and an expensive brown sack of a jacket — yeah, OK, they could picture her being a student here. “We do have a few Mollys,” Panfil said.

But when Nelson sticks his head under Ringwald’s skirt, the room agreed: Today, Molly would sue. When Nelson says she is starting to look fat, you could feel a collective recoil in the room.

“That would never fly,” DiCocco said. “A guy calling a girl ‘fat’ would cross a line.”

“Culturally, things definitely changed,” Serlin said.

Horvath: “At least, another student would have said something to (Nelson) by now.”

Panfil: “I mean, who would even put that much effort into trolling anyone today?”

We sat in a handsome student lounge. Set into a wall in large letters: “Be Positive. Be Proud. Be Spartan” — the sort of hopeful reinforcement, the film argues extravagantly, that boomers could not provide in the 1980s. There were egg chairs and brightly colored leather stools that wouldn’t look out of place in a tech startup or a very cool daycare center. Glenbrook is more like the sunny high schools I think I remember from John Hughes movies than the actual schools in his movies. It’s reality overtaking fiction. Hughes himself, who died in 2009 at 59, knew lots about that. He was, as his films suggest, something of an outsider at Glenbrook North — yet a ridiculously self-confident one. At Glenbrook, Hughes took to dressing modish, like Bob Dylan. He didn’t care about fitting in. He once told an interviewer, if he was made fun of, he’d think, “That’s OK. Picasso would like me.”

After he became a filmmaker, he could be just as sanctimonious as a 15-year-old. It became his superpower. As journalist Bruce Handy writes in “Hollywood High” — an upcoming history of teen movies that places “Breakfast Club” in a continuum alongside “Rebel Without a Cause” and many others — his legacy is showing that high school is actually dominated by various “tribes” of social class, not just the big, blah “teenage monoculture” Hollywood used to depict high school.

What this meant in 1985 was that “The Breakfast Club” seemed to boil away the chaff of high school and reveal the sensitive you. Being a teenager in Hughesville meant brief moments of connection with people who understand, then, bittersweetly, a life of comparable bleakness. It flattered a teenager’s self-importance and offered truths only a teenager could know: The pressure is impossible, your parents don’t listen, and yet, inevitably, you become your parents.

As Ally Sheedy says, your heart dies when you get older. Yes, I remember thinking at 14, it does, as if I knew. It’s here, when “The Breakfast Club” goes deep, the Glenbrook Six connected the most.

As “Breakfast Club” character after character took their swings delivering soliloquies about pressure and parents and popularity, the students went quiet for long stretches and just listened.

The film’s view of the insular nature of cliques: “I’d say, generally, everyone has their friend group and stick to that,” said DiCocco. That part hasn’t changed much. But when asked if they have good relationships with parents — the film’s adults being emotionally absent — the students said they do, almost in unison, way too fast for a Gen-Xer’s ears. They’re disgustingly well-adjusted.

But Hughes’ understanding of pressure — spot on.

After Emilio Estevez describes the intensity of a father demanding a devoted athlete, Panfil said quietly: “That’s still a thing today.” They describe friends groomed to be athletes since they could stand, and practicing musical instruments for absurdly long times. Brown said there is pressure to keep grades up, “just not to the extent in this movie.” Anthony Michael Hall’s Brian is in detention for bringing a flare gun to school, pressure to excel leading to suicidal overtures. That gun, at Glenbrook, would mean an automatic expulsion now, no question, they said. “But (the movie) doesn’t get how this pressure doesn’t just come from parents, but peers,” Panfil said.

“It’s very competitive,” Katz seconded.

“Especially around now,” said Horvath, “when you see people committing to really good schools for college and it starts to make you think less of the schools you applied to.”

When some of the film’s characters are mocked for taking part in afterschool activities, the students shook their heads: none of them can think of a classmate who isn’t involved in activities.

And then the film’s vice principal mentioned he makes $31,000 a year.

Reader, there were actual gasps.

Katz grabbed her phone and quickly researched education salaries in the 1980s: “Yup!” she said, waving her iPhone screen that showed a medium $31,000 for assistant principals around 1980.

About the movie’s reliance on stereotypes — they see a smidge of truth. But, wisely, they see themselves as containing multitudes. Brown played football, now he’s involved in theater: “I see a little of all of these characters in me.” Katz recognized having a little Ringwald and some Anthony Michael Hall. Horvath said he’s seen as “the tall sports guy,” but his favorite activity has actually been youth government groups.

“It’s hard to find just a jock anymore,” said DiCocco.

Also, she said she doubts, as Sheedy, says, the heart dies when you become an adult: “I think passions just change and you find joy in other things and the heart just becomes different then.”

Horvath: “I know I won’t be able to play football my whole life. Lincoln, you might be able to get on stage and perform your whole life …”

Brown: “I could. But probably won’t.”

Horvath: “Some things you can only experience in high school. Then, maybe, what she means is that part of your heart probably does die when you lose what you once loved to do.”

Katz: “But this idea of everyone trudging towards a miserable adulthood — at least now, we’re encouraged to go for dreams. Drew, I remember you saying you wanted to be a very specific kind of doctor. A lot of us are not all that uncertain. We are …”

“Lucky,” Serlin said.

As the movie ended, they sat in silence.

“Somebody should remake it,” Serlin said. She’s studying film at New York University in the fall.

“But it would need five completely different new stereotypes to be accurate,” Panfil said.

“And more diversity,” Serlin said.

“And yet,” Horvath said, “in that remake, in 2025, the Breakfast Club would all be silent and on their phones — the whole detention. They wouldn’t talk to each other at all. OK, maybe they could do a group chat? But whatever it would look like, it wouldn’t look like, what, like 40 years ago?”

———

C2E2: The Chicago Comic & Entertainment Expo runs April 11-13 at McCormick Place South, 2301 S. Martin Luther King Drive. “Don’t You Forget About Me: The Breakfast Club 40th Anniversary Reunion” is 11 a.m. April 12 on the Main Stage; www.c2e2.com

———

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments