How Jim Morrison and The Doors sparked the Rallies for Decency in 1969

Published in Entertainment News

PITTSBURGH — It's gotten to where concerts are canceled, officially, for only two reasons: the undisclosed "illness" and the euphemistic "scheduling conflict," which means they either didn't sell enough tickets or the artist found something better to do.

Back in the day, the cards were all on the table. If the show didn't sell, they just said "poor sales."

This month in 1969, everyone knew that The Doors concert was canceled because Jim Morrison may or may not have dropped his drawers.

On March 22 of that year, The Doors were set to make their Pittsburgh debut at the Civic Arena. It was long awaited because in January 1967 the LA psych-rock band released one of the greatest debut albums of all time, highlighted by the mind-blowing, chart-topping hit, "Light My Fire."

The '67 tour cycle seemingly took them everywhere but Pittsburgh, including Canton and Cleveland, three days before they played "The Ed Sullivan Show," from which they were subsequently banned when Jim Morrison broke the agreement to not sing the word "higher."

That fall '67 East Coast swing ended with the infamous New Haven concert, where, after mocking the police about a backstage incident, Morrison was dragged from the stage and charged with inciting a riot, indecency and public obscenity.

The Doors blew by here in the summer of '68 as well, so the first Pittsburgh show was to be in March 1969, about six months after releasing "Strange Days," the sophomore album with the freakish cover.

On March 1, at a grossly overheated airplane hangar in Miami, Morrison showed up drunk and belligerent and verbally sparred with the crowd, uttering things like "You're all a bunch of slaves!"

Little by little, things got a little out of control. The singer grabbed a cop's hat and threw it into a crowd. Someone jumped on stage and doused Morrison with champagne. He ripped his shirt off and dared the crowd with "Let's see a little skin. Let's get naked." Reportedly, there were takers.

Did Morrison himself "get naked"? No, his band members said. He may have unzipped and stuck his hand down there, but that was it. There were no cellphones. The police claimed that he exposed himself, shouted obscenities and also simulated oral sex on guitarist Robby Krieger. They issued a warrant for his arrest four days later.

In response, Jacksonville, Philadelphia and Toronto all canceled, and so did Pittsburgh, under pressure from Mayor Joseph Barr himself.

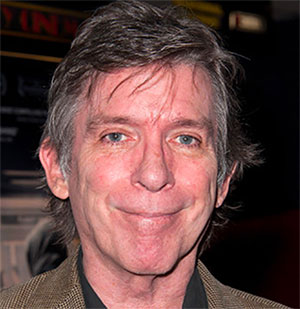

"I had the exclusivity on rock shows there at the arena," promoter Pat DiCesare told the Post-Gazette on Monday, "and I didn't want to cause any aggravation, so I was willing to forget The Doors even though I was convinced it was gonna sell out, if it was going to cause trouble."

DiCesare canceled on March 11, 1969, explaining that it was because of the Miami incident. He got his $14,000 deposit back but lost all the money on the advertising and promotion.

Rallies for Decency

Three weeks after the Miami concert, and one day after the canceled Pittsburgh concert, something almost unbelievable happened. Thirty thousand people packed into the Orange Bowl for a teenage Rally for Decency, some waving signs saying, "Down With Obscenity."

The front-page AP story in the Post-Gazette noted that it consisted of "three-minute talks about God, parents, patriotism, sexuality and brotherhood" and appearances by Jackie Gleason, Anita Bryant and The Lettermen, who prided themselves as being the "squares" of popular music.

A battle was on for the hearts and minds of American youth who had gone through the Summer of Love of 1967 and were on the way to Woodstock.

The Orange Bowl rally, coordinated by 17-year-old high school football player Mike Levesque, sprung from a Catholic youth group meeting two days after the Miami concert.

"I believe this kind of movement will snowball across the country and perhaps around the world," Gleason said, and the comedic superstar was partially right.

Levesque received a letter of appreciation from President Richard Nixon and calls from radio stations and organizers in other cities to stage their own rallies, which took place in Birmingham, Ala., Minneapolis, Minn., Austin, Texas, and other cities.

Baltimore controller Hyman A. Pressman declared this Clean Teens movement to be "the best thing that has happened in this country in a long time."

So, Baltimore got in on the action, at Memorial Stadium in April, and ... it didn't go so well.

It did draw 45,000, but the next-day headline read, "Decency Rally Ends in Baltimore Brawl."

At least 200 people were stabbed, beaten or pelted with rocks. The mistake was the youth organizers teasing that soul icon James Brown might be there. Instead, the crowd got a bunch of boring speakers and some second-rate local bands on a bad sound system.

"There were too many hoodlums in the stands," a city councilman explained, adding, "There was too much emphasis on the rock 'n' roll music, and not enough on decency."

A Detroit rally was another bust. They expected 15,000 at Cobo Hall and got 2,000, for a couple unnamed rock groups and The Irish Rovers.

The UPI reporter interviewed a 10th-grader, who admitted she was there to meet boys.

"Decency? Well, it's like love your parents and love the flag," she said. "I don't want to be told stuff like that."

Pittsburgh had two decency rallies. In May, the folk group New World Singers of Youth for Christ International drew about 100 people to Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall in Oakland. In July, Steve Gilbreath, a member of Up With People from Alabama who was inspired by the Miami rally, held one at the Syria Mosque with the Good News Singers. About 800 people watched them do folk and religious songs and also cover The Lettermen

Break on through

DiCesare was not interested in jumping on the decency rally craze.

"I didn't give that a lot of attention," he says.

He wanted the Doors back, and so he followed the band's trek through the summer, during which they played Chicago, Minneapolis, Los Angeles and a couple other cities, while "Touch Me" spun on the radio.

"We waited until some of these other dates played," DiCesare says. "I kept in touch with Bill Siddons, who was the manager of the act, and Bill convinced me that he had Jim under control and if I played him in Pittsburgh, Jim would, you know, behave himself.

"With all these shows, the managers of these theaters and arenas, they expected people to sit in their seats because they were all older and when they grew up, that's what it was when you went to a theater. But that didn't happen in the '60s, especially with an act like The Doors. I mean, the kids got excited. They all rushed the stage."

It was common after the shows then, DiCesare says, for a local TV crew to swoop in and show the arena floor in disarray, so rock concerts were an uphill battle on multiple fronts.

The Doors show booked for Saturday, Sept. 20, and briefly became a political football for Constitutional Party mayoral candidate George Shankey.

"The Democrats and Republicans are both to blame for this," he declared in the PG. "The Democrats run the arena and the Republicans have done nothing to stop the show."

For all the commotion, it's surprising there were no local reviews of The Doors engagement. The only mention was an item in Harold Cohen's column six days later, quoting a letter from DiCesare "that a well-mannered Jim Morrison and his colleagues played to a near-capacity crowd of 12,000.

"At one point," he added, "the enthusiastic audience began to leave their seats and run to the front of the stage, but Jim, contrary to what rumors would have you believe, asked fans to go back quietly and they did. Order was almost immediately restored, and the show ended peacefully. Our thanks to Morrison for the beautiful way he handled a situation that could've gotten out of control.

"I thought you would like to know this because so often it's only the bad things about a rock concert which make the news."

This is the end

Before Morrison's death in July 1971, The Doors came back one more time, on May 2, 1970, a few months after releasing their fifth album, "Morrison Hotel." The 16-song set, which included a 17-minute version of "When the Music's Over," can be heard on the album "The Doors — Live In Pittsburgh 1970."

Of that show, Uncut declared, "The Doors camp has long held that the band's May 2, 1970, show at the Pittsburgh Civic Arena was the tightest performance of its extensively recorded final tour, as the wildly erratic Jim Morrison showed up that night neither remote nor out of it but clear and focused. ...

"It's safe to say that 'Live In Pittsburgh' is the first Doors live album that captures the band at its spellbinding peak. From this point forward, no longer will the Boomer need to explain, 'You had to be there.' "

As for the Rallies for Decency, there's just a few scattered mentions of them in the early '70s and, oddly, no further reported activism from Levesque or Gilbreath.

A decade passed, and then, shocked by the arrival of Madonna, Prince, W.A.S.P. and other '80s provocateurs, Tipper Gore picked up the mantle with the Parents Music Resource Center.

In terms of concerts that DiCesare was pressured to cancel, "The Doors were the only one," he says. "The Doors, that was it."

________

© 2025 the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Visit www.post-gazette.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments