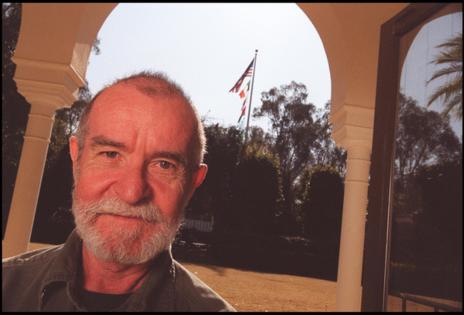

Appreciation: Playwright Athol Fugard proved the pen could be mightier than the sword

Published in Entertainment News

W.H. Auden, meditating on the role of the artist in a poem by W.B. Yeats, concluded that poetry "makes nothing happen." While generally true, the precept doesn't hold in the case of playwright Athol Fugard, whose body of work helped transform the history of his nation.

Born in Middelburg, South Africa, in 1932 to an immigrant English father of Irish descent and a mother from an Afrikaner family, Fugard lived through the rise and fall of apartheid. His career brought an international spotlight to this system of racial segregation in plays that afflicted consciences and fomented activism at home and abroad.

Fugard, who died Saturday at age 92, was part of a resistance movement in South Africa that found its voice in the theater.

The stage became one of the few places where the flames of dissent, militantly stomped out in other quarters of society, grew to a conflagration seen around the world.

"At the height of the apartheid era, the Market Theatre in Johannesburg and the Space Theatre in Cape Town, both defiantly nonracial venues in a racially divided country, produced shattering plays about black life under the apartheid regime," recalled playwright and director Emily Mann in a Times article reflecting on Nelson Mandela's legacy to the arts. Fugard, who was on the front lines of this activity, later acknowledged that, in the South African case, the pen was indeed mightier than the sword.

Citizenship had supplied Fugard with his mission as a writer. But he understood the difference between art and politics and resisted anyone dictating his agenda as a playwright.

"No writer must ever presume to tell another writer what his or her political responsibilities are," he told the Paris Review. "It is a poet's right in South Africa to write a poem that seemingly has no political resonance."

At the same time, he recognized, in a talk he gave at Rhodes University in 1991, that it probably wasn't possible to "tell a South African story accurately and truthfully and for it not to have a political spin-off." Complacency for him was unthinkable when a majority of his fellow citizens were denied their fundamental liberties.

But Fugard, who though primarily known as a playwright was also an accomplished novelist, director and actor, understood the limits of propaganda. Only art, unflinchingly committed to the truth, has the potential to influence hearts and minds. He was determined to become, in all his work, a witness.

The contradictions inherent in his position as a white South African dissident became a source of dramatic conflict in his plays. Fugard couldn't renounce his identity, but he could scrutinize it with ruthless honesty, subject it to imaginative tests and share his ethical findings.

For all the political freight of Fugard's works, he was a deeply personal writer. It wasn't so much ideas or arguments that inspired his plays but human beings in all their messy complications.

His notebooks, bursting with images and anecdotes of real-life folks whose stories caught his attention, provided a storehouse for his plays. Fugard wasn't in a rush to translate this material to the stage. The figures in his journals would have to wait until something within him summoned them into theatrical action.

Before he could inhabit the psychology of his characters, his own psychology had to be stirred. As he explained in his speech at Rhodes University, "The Swedish poet [Tomas] Tranströmer has a line to the effect that when the external event coincides with the internal reality the poem happens. That is how it works for me as a playwright."

Time and again it was the reality of what Fugard called "human desperation" that inflamed his imagination. "Nobody has ever written a good play about a group of happy people who started off happy and who were happy all the way through," he elaborated. "And in South Africa if you have found a desperate individual, nine times out of 10 you have also found a desperate political situation."

Yet the autobiographical element is present even in places where it might seem conspicuously absent. "Blood Knot," the breakthrough play in which he found his voice as a dramatist, is about two brothers from the same mother, one dark-skinned, the other light-skinned. Fugard, who took on the role of the light-skinned brother opposite Zakes Mokae in the 1961 Johannesburg premiere, has these siblings wrestle for their dignity and autonomy in a one-room shack.

The genesis of the play, as Fugard told the Paris Review, "had absolutely nothing to do with the racial situation in South Africa." He described the "seminal moment" as the wrenching sight of his brother sleeping one night, an image that filled his heart with pity.

"My brother is a white man like myself," he explained. "I looked down at him, and saw in that sleeping body and face, all his pain. Life had been very hard on him, and it was just written on his flesh. It was a scalding moment for me. I was absolutely overcome by my sense of what time had done to what I remembered as a proud and powerful body."

The play, which radically recasts the fraternal relationship, developed far beyond its originating impetus. "Blood Knot" parodies the charade of official racial differences in scenes in which the brothers take turns donning a suit of white man's clothes purchased for a romantic encounter with a white woman introduced via a personal ad.

An early masterpiece, "Blood Knot" established a paradigm for Fugard, whose plays are distinguished by their small casts, static locations and tinderbox emotions. Just as important is the role of playacting. His characters may be confined by their circumstances but their imaginations are set free in theatrical games, pantomimes and nostalgic reveries.

The brothers of "Blood Knot" lampoon the meaning of whiteness with costume choices. Young Haley tyrannically conducts "the boys" in " 'Master Harold'…and the Boys" to reenact memories of his childhood. The Black prisoners of "The Island" turn to Sophocles' "Antigone" to understand the injustice of their own situation.

Theatrical craft was of preeminent importance for Fugard, who was a less conventional dramatist than is often assumed. His poetic style varied with his thematic content, both of which were contingent on the idiosyncrasies of his characters. The voices of his protagonists, which is to say the cadences of their social identities, determine not just the sound but the shape of their stories. In upholding the sanctity of the spoken word, Fugard took his place in the oral tradition of Homer.

Stylistically, he contained multitudes. His early dramas from the 1960s — "Blood Knot," "Hello and Goodbye" and "Boesman and Lena" — evoke the existential concerns of the Absurdist playwrights from the era. Yet the stark metaphysical truths of these plays are inseparable from their brutal South African context.

Fugard's "workshop" plays from the early 1970s, devised with actors Winston Ntshona and John Kani, opened a more direct channel to the lived reality of Black South Africans. "Sizwe Bansi Is Dead" and "The Island" have the propulsive energy of performance art, registering their shocks to the audience through compression and raw theatricality. "Statements After an Arrest Under the Immorality Act," although credited to Fugard alone, was developed along similar lines of guided improvisation and other techniques aimed at, in the author's own words, "releasing the creative potential of the actor."

Working in opposition to apartheid laws placed Fugard in legal jeopardy. His passport was seized after a televised performance of "Blood Knot" in London in 1967 and not returned until 1971. His work was banned by the authorities and he and his family were placed under surveillance.

Producing "Sizwe Bansi Is Dead" required not only courage but ingenuity. "We felt that the play was far too dangerous for us to go public with it; there was the problem of mixed audiences," Fugard recounted in the Paris Review. "So we launched the play by underground performances to which people had to have a specific invitation — a legal loophole in the censorship structure in South Africa, and one we continued to exploit for many years."

This "underground period" brought much interference from the police. "They rolled up once or twice and threatened to close us down, arrest us — the usual bully tactics of security police anywhere in the world," Fugard said. "We just persisted, carried on, and survived it. We eventually did go public with 'Sizwe Bansi,' many years later, but only after it had played in London and New York. After that, we felt that the play's reputation protected us."

The end of apartheid in the early 1990s transformed Fugard's playwriting but didn't rob him of his purpose. Always deeply personal, his work became more conspicuously autobiographical. The figure of the author, typically a crotchety older man with an impish sense of humor and unabashed literary fervor, became a staple of his later work. But age didn't mellow his subversive spirit. The inquiry into social justice merely continued down more inward byways.

"Valley Song," the greatest of the post-apartheid works, offers a lyrical meditation on the human cost of change, the losses exacted by progress. Fugard, who was a potent moral force on stage, performed the double role of Author and Buks, a mixed-race tenant farmer who must give his granddaughter the freedom to leave their home so that she can pursue her dream of being a famous singer.

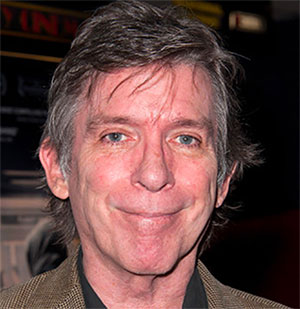

Fugard developed a strong relationship with L.A.'s Fountain Theatre, where his late plays found welcome in the kind of grassroots environment of his early years. "After being impressed by the company's L.A. premiere of "The Road to Mecca," Fugard entrusted Stephen Sachs with the world premiere of "Exits and Entrances." "Victory," "The Blue Iris" and "The Train Driver" notably had their U.S. premieres at the Fountain.

"Working alongside Athol Fugard, directing his new plays for ten years, was a profound honor and one of the most rewarding periods of my professional life," Sachs, who retired last year as the Fountain's co-founding artistic director, wrote in an email. "He painted on a small canvas upon which one glimpsed the world."

"The Painted Rocks at Revolver Creek," which had its West Coast premiere at the Fountain, brings the Nelson Mandela-era mandate of truth and reconciliation to the domain of individual conscience. A comparatively small addition to his oeuvre, the drama provides complex characterizations that are a gift to actors — a constant of Fugard's playwriting.

Fugard defined the essence of what he called "pure theater" as nothing more "than the actor and the stage, the actor in space and silence." As an artist he resisted labels, but he conceded that if his work is to be categorized "then it must be as 'actors' theatre.' "

Humanity was always at the core of Fugard's art. In "A Lesson From Aloes," a character quotes Thoreau: "There is a purpose to life, and we will be measured by the extent to which we harness ourselves to it." By this standard, Fugard was a model to us all.

______

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments