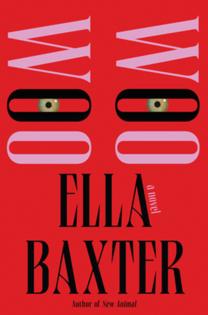

Ella Baxter wrote a 20,000-word letter to her stalker. It became her novel, 'Woo Woo'

Published in Books News

Ella Baxter’s novel “Woo Woo” wasn’t supposed to be published.

It wasn’t even meant to be a novel, Baxter says. She’d sat down to feverishly pen a letter to the stalker who’d been driving her mad for a year and a half. Twenty-thousand words later, the catharsis was too potent, the energy that kept the words flowing was too invigorating, for it to end there.

“I was sent these letters by someone who clearly knew me,” Baxter tells me over a Zoom call from her home in Melbourne. “They were really violent, predatory, angry letters, but it was clearly someone close to me. It was terrifying because they knew intimate details about my life, but I had no idea who it was.”

Baxter went to the police, she went to a psychic, she took self-defense classes. She moved and installed heightened security measures in her home. “Nothing was happening, so my friend said, ‘Just write your own letter back as an experiment, just to get some agency in the situation with no view to sending the letter anywhere.’”

The sculptural artist and novelist says that getting all of her rage, frustration and horror out on the page was the most beautiful thing she could have done. “Because I felt so powerless,” she continues. “And then the fantasies I had about confronting this person developed, and then the person in the letter became a protagonist.”

And then the 20,000-word missive became her 249-page novel “Woo Woo.”

When she’d initially finished the manuscript, she printed it out and lit it on fire over a barbecue grill in her garden. She emailed her agent and said what she’d written was “too nuts” to ever publish, adding, “This can’t see the light of day.”

In a July essay for the Guardian, Baxter wrote that for a while, the letters from the stalker stopped. “The nights become quiet. I moved twice more and fell pregnant. The night I gave birth someone glued the locks shut to my home. When I inspected the damage I saw there were hammer marks smattered across the wood of the door. I held my newborn in one arm and brought my face close to the dents. Someone came to my home, in the night, with a hammer.”

“I looked down at my baby and grew, in the space of a few seconds, 10 feet taller,” she continues in the essay. “I was monstrous, livid. A petrol can in the shape of a woman. My baby and I become bigger than everything else. I lifted him up to eye level and kissed his face as I walked to my study. In the subject line of a new email to my agent, I wrote: ‘This is an arrow aimed at only one head.’ I attached a copy of my manuscript and used my baby’s tiny index finger to press send.”

“Woo Woo” follows Sabine, a conceptual artist preparing for a buzzworthy exhibition of self-portraits which she hopes will be pivotal for her career. In the days leading up to the gallery showing, Sabine is drowning in insecurity and becoming increasingly neurotic. “She needed so much (wine, encouragement, reassurance), but she was unable to voice her needs because she couldn’t focus on anything beyond the maddening pink and the unbearable weight that she would endure as a successful artist in a room full of more interesting graduates.”

To make matters worse, a man resembling a Rembrandt portrait appears in her garden and begins slipping threatening letters underneath her door and cramming them through her mail slot. When she tells her overworked chef husband Constantine — who provides “some yang to her constant, thrumming yin” — he tries to be supportive but doesn’t know exactly how. He’s not sure whether “the Rembrandt Man” is real or a figment of Sabine’s often-deteriorating psyche just before a show. When he asks to see the letters, she tells him she lost several and, in another case, eaten one.

And then there’s the ghost that Sabine frequently chats with, Carolee Schneemann, her mentor, naturally. “We are going to look at creating false mayhem — that’s true art — but first we must identify the problem … I’m talking to you about subterfuge, about trickery and smoke and mirrors, false mayhem,” Schneemann counsels.

Sabine does have all the markings of an unreliable narrator. The reader might bounce back and forth between being concerned about Sabine’s physical safety and worrying that the pressure of the exhibition has warped into an intense episode of psychosis. Or could it all be in the name of art? “She prostrated herself before the altar of art,” Baxter writes. “She spent her whole life in the process of making or recovering from art, and when she wasn’t doing either of those two things she was looking at other people’s art.”

When Sabine is later chased through the streets by the Rembrandt man in the midst of a livestream, her devoted Gen Z followers praise her commitment to performative art. The gallery hosting her exhibit comments, “What a thought-provoking piece Sabine provided for us this evening … Brava (Dare we say, encore?)!”

Baxter says that she didn’t intend to write the Rembrandt man as possibly hallucinatory, and yet many of her readers have asked if Sabine was merely imagining him. “I wrote it as if all those things were absolutely real and legitimate, and there was no opaqueness for me when I was writing it,” she says. “I was stalked while I was releasing my debut novel. The freakouts, the paranoia, those were all things I had first-hand insight into, and I didn’t really feel like I was trying to ever create doubt that it was happening.

“But I think it’s interesting that doubt is read into her,” Baxter continues. “Why do we doubt it? I’m so curious to know why people aren’t quite sure if it’s happening to her or not. Is it because she’s hysterical? Is it because she’s leaning into it?”

Baxter says that her experience with a stalker sowed intense paranoia and that the act of stalking is a kind of psychological warfare. She was never sure if she’d heard a noise she should be legitimately concerned about or if her floorboards were simply creaky. As she was promoting her first novel, “New Animal” (in the midst of the stalking), she was terrified to share the time and locations of her book events. She became jumpy and began to imagine things, “All of these [symptoms] that lend themselves to you not being a reliable narrator, even though it is actually happening to you in some degree of truth.”

Baxter eventually stopped talking about what was happening in her real life because she didn’t want to seem crazy, but she wanted to capture the isolation and strangeness of her experience with “Woo Woo.” As for Baxter’s stalker, the letters eventually stopped and the sender was never definitively identified.

“I’ve never written or made anything fueled by rage alone, but ‘Woo Woo’ was, and it’s so crystallizing. When you’re in that state where you’re just like, this is completely unreasonable, I have to do something about it. I found it quite clear and icy and enjoyable to make an enjoyable space to inhabit while I was making art.”

©2024 MediaNews Group, Inc. Visit ocregister.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments