A warning for Democrats from the Gilded Age and the 1896 election

Published in News & Features

More than five months after President Donald Trump defeated Kamala Harris, Democrats are still trying to understand why they lost the election and the Senate majority – and how the party can regroup.

These concerns have only increased in the wake of Trump’s sustained activity at the start of his second term. The American public has witnessed a Democratic Party struggling to craft a coherent strategy.

Recently, Trump has joined a chorus of people likening the current political period to the Gilded Age – the late 19th-century period known for economic industrialization and wealth inequality.

As a political scientist focused on electoral politics, I believe the Gilded Age provides a warning for the Democrats’ current situation, as the party’s internal struggles hampered its ability to wage successful national campaigns.

Scholars of U.S. political history often refer to the bulk of the 19th century as the party period due to the degree to which party politics permeated society. Parties framed political discourse through the creation of “brands” centered on distinct ideologies.

These ideologies offered coherent ideas of what it meant to be a Democrat or a Republican.

Democrats opposed a strong national government in favor of states’ rights. They resisted vesting too much economic authority in the national government. And they used their states’ rights position to justify human enslavement and racially discriminatory policies.

Republicans embraced national authority over states’ rights. It was a vision centered on a national political economy that fostered manufacturing and industrialization. This economic approach was accompanied at times by opposition to immigration in often nativist and racist rhetoric.

The Gilded Age has been compared with the present. That’s due, in part, to the period’s rapid industrialization, increased immigration and prominent debates over economic policy.

And like today, these Gilded Age years, roughly from 1870 to 1900, witnessed intense competition between Democrats and Republicans, during which only about seven states were contested in any given election due to the regional basis of support for each party.

From 1860 to 1912, Democrats won the White House only twice – Grover Cleveland in 1884 and 1892. But they won the popular vote two more times, while losing the Electoral College – Samuel Tilden in 1876 and Cleveland in 1888.

Further, from the 1870s to the 1890s, party control of Congress tended to rely on slim majorities.

Democrats usually held the House and Republicans controlled the Senate.

The 1880s and 1890s were characterized by debates over economic policies, primarily the protective tariff. That tariff was supported by Northern industrialists to protect domestic industry and opposed by Southern agrarians. The U.S. monetary standard, which determines how value is measured, also dominated discussions.

The 1888 election revealed tensions among Democrats, primarily over the tariff, that became a harbinger of the party’s struggles in 1896. The party’s inability to reconcile competing constituencies in its coalition and offer a coherent message on the tariff ultimately cost them the White House.

After winning reelection in 1892, Democrat Cleveland faced an economic depression that impeded the goals of his second term. The Democrats lost both chambers of Congress in the ensuing midterm election.

The battle over the monetary standard consumed the 1896 election.

From the 1870s-1890s, debates over whether greenbacks, or paper currency, should be redeemable in gold or silver ebbed and flowed.

Republicans, buoyed by wealthy financiers, tended to support maintaining the gold standard only. Democrats, who courted laborers and farmers, usually supported the increased circulation of greenbacks redeemable in both gold and silver.

The economic depression in 1893 heightened tensions on this issue, as many Americans sought to pay off their debts with cheaper currency.

At their national convention, Democrats adopted the pro-silver position and nominated a populist firebrand for president, William Jennings Bryan.

Republicans also faced internal divisions on the issue. But, as in 1888, they were able to overcome these tensions to maintain their coalition and supported the gold standard in their platform.

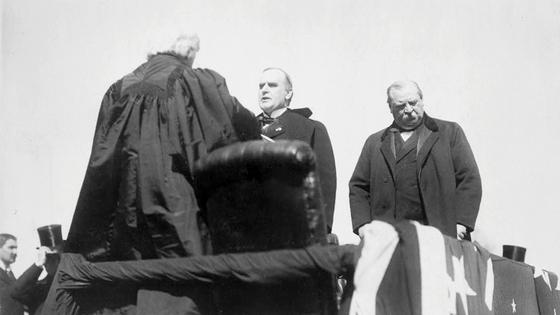

The Republican candidate, William McKinley, defeated Bryan. The outcome solidified Republican primacy for 30 years.

Internal strife in the late 19th century hindered Democrats’ ability to advance a unified voice, mobilize their voters and attract new ones. In 1888 and 1896, these divisions harmed Democrats’ electoral prospects. Their organizational problems and intense internal discord proved too much for Bryan to overcome.

Scholar James Reichley contends that the Republicans’ more effective organizing after Reconstruction may have resulted in a coherent message compared with the Democrats.

And a lack of enthusiasm on the part of Democratic voters contributed to Republican success in 1894 and 1896, according to historian Richard White. Republicans mobilized their base and attracted new voters, while Democrats did not.

These elections solidified voter alignments until 1932.

Although Democrat Woodrow Wilson held the presidency from 1913 to 1921, Republicans dictated national policy and controlled Congress for most of those years. It took a massive economic depression to return the Democrats to the majority on the national level.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Adam M. Silver, Emmanuel College

Read more:

Reducing diversity, equity and inclusion to a catchphrase undermines its true purpose

A need for chaos powers some Americans’ support for Elon Musk taking a chainsaw to the US government

Beggar thy neighbor, harm thyself: Tariffs like Trump’s come with pitfalls, history shows

Adam M. Silver does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments