Trump’s desire to ‘un-unite’ Russia and China is unlikely to work – in fact, it could well backfire

Published in News & Features

Is the U.S. angling for a repeat of the Sino-Russian split?

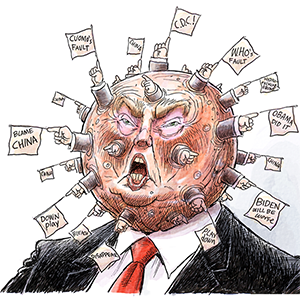

In an Oct. 31, 2024, interview with right-wing pundit Tucker Carlson, President Donald Trump argued that the United States under Joe Biden had, in his mind erroneously, pushed China and Russia together. Separating the two powers would be a priority of his administration. “I’m going to have to un-unite them, and I think I can do that, too,” Trump said.

Since returning to the White House, Trump has been eager to negotiate with Russia, hoping to quickly bring an end to the war in Ukraine. One interpretation of this Ukraine policy is that it serves what Trump was getting at in his comments to Carlson. Pulling the U.S. out of the European conflict and repairing ties with Russia, even if it means throwing Ukraine under the bus, can be seen within the context of a shift of America’s attention to containing Chinese power.

Indeed, after a recent call with Russian President Vladimir Putin, Trump told Fox News: “As a student of history, which I am – and I’ve watched it all – the first thing you learn is you don’t want Russia and China to get together.”

The history Trump alludes to is the strategy of the Nixon era, in which the U.S. sought to align with China as a counterbalance to the Soviet Union, encouraging a split between the two communist entities in the process.

Yet if creating a fissure between Moscow and Beijing is indeed the ultimate aim, Trump’s vision is, I believe, both naive and shortsighted. Not only is Russia unlikely to abandon its relationship with China, but many in Beijing view Trump’s handling of the Russia-Ukraine war –- and his foreign policy more broadly – as a projection of weakness, not strength.

Although Russia and China have at various times in the past been adversaries when it suited their interests, today’s geopolitical landscape is different from the Cold War era in which the Sino-Soviet split occurred. The two countries, whose relationship has grown steadily close since the fall of the Soviet Union,have increasingly shared major strategic goals – chief among them, challenging the Western liberal order led by the U.S.

Both China and Russia have, in recent years, adopted an increasingly assertive stance in projecting military strength: China in the South China Sea and around Taiwan, and Russia in former Soviet satellite states, including Ukraine.

In response, a unified stance formed by Western governments to counter China and Russia’s challenge has merely pushed the two countries closer together.

In February 2022, just as Russia was preparing its invasion of Ukraine, Presidents Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping announced a “friendship without limits” – in a show of unified intent against the West.

China has since become an indispensable partner for Russia, serving as its top trading partner for both imports and exports. In 2024, bilateral trade between China and Russia reached a record high of US$237 billion, and Russia now relies heavily on China as a key buyer of its oil and gas. This growing economic interdependence gives China considerable leverage over Russia and makes any U.S. attempt to pull Moscow away from Beijing economically unrealistic.

That doesn’t mean the Russian-Chinese relationship is inviolable; areas of disagreement and divergent policy remain.

Indeed, there are areas that Trump could exploit if he were to succeed in driving a wedge between the two countries. For example, it could serve Russia’s interests to support U.S. efforts to contain China and discourage any expansionist tendencies in Beijing – such as through Moscow’s strategic ties with India, which China views with some alarm – especially given that there are still disputed territories along the Chinese-Russian border.

Putin isn’t naive. He knows that with Trump in office, the deep-seated Western consensus against Russia – including a robust, if leaky, economic sanctions regime – isn’t going away anytime soon. In Trump’s first term, the U.S. president likewise appeared to be cozying up to Putin, but there is an argument that he was even tougher on Russia, in terms of sanctions, than the administrations of Barack Obama or Joe Biden.

So, while Putin would likely gladly accept a Trump-brokered peace deal that sacrifices Ukraine’s interests in favor of Russia, that doesn’t mean he would be rushing to embrace some kind of broader call to unite against China. Putin will know the extent to which Russia is now reliant economically on China, and subservient to it militarily. In the words of one Russian analyst, Moscow is now a “vassal” or, at best, a junior partner to Beijing.

China for its part views Trump’s peace talks with Russia and Ukraine as a sign of weakness that potentially undermines U.S. hawkishness toward China.

While some members of the U.S. administration are undoubtedly hawkish on China – Secretary of State Marco Rubio views the country as the “most potent and dangerous” threat to American prosperity – Trump himself has been more ambivalent. He may have slapped new tariffs on China as part of a renewed trade war, but he has also mulled a meeting with President Xi Jinping in an apparent overture.

Beijing recognizes Trump’s transactional mindset, which prioritizes short-term, tangible benefits over more predictable long-term strategic interests requiring sustained investment.

This changes the calculation over whether the U.S. may be unwilling to bear the high costs of defending Taiwan. Trump, in a deviation from his predecessor, has failed to commit the country to defending Taiwan, the self-governing island claimed by Beijing.

Rather, Trump had indicated that if the Chinese government were to launch a military campaign to “reunify” Taiwan, he would opt instead for economic measures like tariffs and sanctions. His apparent openness to trade Ukraine territory for peace now has made some in Taiwan concerned over Washington’s commitment to long-established international norms.

China has taken another key lesson from Russia’s experience in Ukraine: The U.S.-led economic sanctions regime has serious limits.

Even under sweeping Western sanctions, Russia was able to stay afloat through subterfuge and with support from allies like China and North Korea. Moreover, China remains far more economically intertwined with the West than Russia, and its relatively dominant global economic position means that it has significant leverage to combat any U.S.-led efforts to isolate the country economically.

Indeed, as geopolitical tensions have driven the West to gradually decouple from China in recent years, Beijing has adapted to the resulting economic slowdown by prioritizing domestic consumption and making the economy more self-reliant in key sectors.

That in part also reflects China’s significant global economic and cultural strength. Coupled with this has been a domestic push to win countries in the Global South around to China’s position. Beijing has secured endorsements from 70 countries officially recognizing Taiwan as part of China.

As such, Trump’s plan to end the Russia-Ukraine war by favoring Russia in the hope of drawing it into an anti-China coalition is, I believe, likely to backfire.

While Russia may itself harbor concerns about China’s growing power, the two country’s shared strategic goal of challenging the Western-led international order — and Russia’s deep economic dependence on China — make any U.S. attempt to pull Moscow away from Beijing unrealistic.

Moreover, Trump’s approach exposes vulnerabilities that China could exploit. His transactional and isolationist foreign policy, along with his encouragement of right-wing parties in Europe, may strain relations with European Union allies and weaken trust in American security commitments. Beijing, in turn, may view this as a sign of declining U.S. influence, giving China more room to maneuver, noticeably in regard to Taiwan.

Rather than increasing the chances of a Sino-Russia split, such a shift could instead divide an already fragile Western coalition.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Linggong Kong, Auburn University

Read more:

How Elon Musk’s deep ties to – and admiration for – China could complicate Trump’s Beijing policy

Trump silences the Voice of America: end of a propaganda machine or void for China and Russia to fill?

Chinese anger at sale of Panama Canal ports to US investor highlights tensions between the two superpowers

Linggong Kong does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments