As mountain glaciers melt, risk of catastrophic flash floods rises for millions − World Day for Glaciers carries a reminder

Published in News & Features

In mountain ranges around the world, glaciers are melting as global temperatures rise. Europe’s Alps and Pyrenees lost 40% of their glacier volume from 2000 to 2023. These and other icy regions have provided freshwater for people living downstream for centuries – almost 2 billion people rely on glaciers today. But as glaciers melt faster, they also pose potentially lethal risks.

Water from the melting ice often drains into depressions once occupied by the glacier, creating large lakes. Many of these expanding lakes are held in place by precarious ice dams or rock moraines deposited by the glacier over centuries.

Too much water behind these dams or a landslide into the lake can break the dam, sending huge volumes of water and debris sweeping down the mountain valleys, wiping out everything in the way.

These risks and the loss of freshwater supplies are some of the reasons the United Nations declared 2025 the International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation and March 21 the first World Day for Glaciers. As an Earth scientist and a mountain geographer, we study the impact that ice loss can have on the stability of the surrounding mountain slopes and glacial lakes. We see several reasons for increasing concern.

Most glacial lakes began forming over a century ago as a result of warming trends since the 1860s, but their abundance and rates of growth have risen rapidly since the 1960s.

Many people living in the Himalayas, Andes, Alps, Rocky Mountains, Iceland and Alaska have experienced glacial lake outburst floods of one type or another.

A glacial lake outburst flood in the Himalayas in October 2023 damaged more than 30 bridges and destroyed a 200-foot-high (60-meter) hydropower plant. Residents had little warning. By the time the disaster was over, more than 50 people had died.

Juneau, Alaska, has been hit by several flash floods in recent years from a glacial lake dammed by ice on an arm of Mendenhall Glacier. Those floods, including in 2024, were driven by a melting glacier that slowly filled a basin below it until the basin’s ice dam broke.

Avalanches, rockfalls and slope failures can also trigger glacial lake outburst floods. These are growing more common as frozen ground known as permafrost thaws, robbing mountain landscapes of the cryospheric glue that formerly held them together. These slides can create massive waves when they plummet into a lake. The waves can then rupture the ice dam or moraine, unleashing a flood of water, sediment and debris.

That dangerous mix can rush downstream at speeds of 20-60 mph (30-100 kph), destroying homes and anything else in its path.

The casualties of such an event can be staggering. In 1941, a huge wave caused by a snow and ice avalanche that fell into Laguna Palcacocha, a glacial lake in the Peruvian Andes, overtopped the moraine dam that had contained the lake for decades. The resulting flood destroyed one-third of the downstream city of Huaraz and killed between 1,800 and 5,000 people.

In the years since, the danger there has only increased. Laguna Palcacocha has grown to more than 14 times its size in 1941. At the same time, the population of Huaraz has risen to over 120,000 inhabitants. A glacial lake outburst flood today could threaten the lives of an estimated 35,000 people living in the water’s path.

Governments have responded to this widespread and growing threat by developing early warning systems and programs to identify potentially dangerous glacial lakes. Some governments have taken steps to lower water levels in the lakes or built flood diversion structures, such as walls of rock-filled wire cages, known as gabions, that divert floodwaters from villages, infrastructure or agricultural fields.

Where the risks can’t be managed, communities have been encouraged to use zoning that prohibits building in flood-prone areas. Public education has helped build awareness of the flood risk, but the disasters continue.

The dramatic nature of glacial lake outburst floods captures headlines, but those aren’t the only risks. As scientists expand their understanding of how the world’s icy regions interact with global warming, they are identifying a number of other phenomena that can lead to similarly disastrous events.

Englacial conduit floods, for instance, originate inside of glaciers, commonly those on steep slopes. Meltwater can collect inside massive systems of ice caves, or conduits. A sudden surge of water from one cave to another, perhaps triggered by the rapid drainage of a surface pond, can set off a chain reaction that bursts out of the ice as a full-fledged flood.

Thawing mountain permafrost can also trigger floods. This permanently frozen mass of rock, ice and soil has been a fixture at altitudes above 19,685 feet (6,000 meters) for millennia.

Freezing helps keep mountains together. But as permafrost thaws, even solid rock becomes less stable and is more prone to breaking, while ice and debris are more likely to become detached and turn into destructive and dangerous debris flows. Thawing permafrost has been increasingly implicated in glacial lake outburst floods because of these new sources of potential triggers.

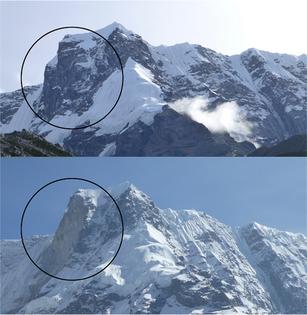

In 2017, nearly a third of the solid rock face of Nepal’s 29,935-foot (6,374-meter) Saldim Peak collapsed and fell onto the Langmale glacier below. Heat generated by the friction of rock falling through air melted ice, creating a slurry of rock, debris and sediment that plummeted into Langmale glacial lake below, resulting in a massive flood.

These and other forms of glacier-related floods and hazards are being exacerbated by climate change.

Flows of ice and debris from high altitudes and the sudden appearance of meltwater ponds on a glacier’s surface are two more examples. Earthquakes can also trigger glacial lake outburst floods. Not only have thousands of lives been lost, but billions of dollars in hydropower facilities and other structures have also been destroyed.

The International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation and World Day for Glaciers are reminders of the risks and also of who is in harm’s way.

The global population depends on the cryosphere – the 10% of the Earth’s land surface that’s covered in ice. But as more glacial lakes form and expand, floods and other risks are rising. A study published in 2024 counted more than 110,000 glacial lakes around the world and determined 10 million people’s lives and homes are at risk from glacial lake outburst floods.

The U.N. is encouraging more research into these regions. It also declared 2025 to 2034 the “decade of action in cryospheric sciences.” Scientists on several continents will be working to understand the risks and find ways to help communities respond to and mitigate the dangers.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Suzanne OConnell, Wesleyan University and Alton C. Byers, University of Colorado Boulder

Read more:

We’ve been studying a glacier in Peru for 14 years – and it may reach the point of no return in the next 30

The water cycle is intensifying as the climate warms, IPCC report warns – that means more intense storms and flooding

What drives sea level rise? US report warns of 1-foot rise within three decades and more frequent flooding

Suzanne OConnell receives funding from The National Science Foundation

Alton C. Byers does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments