'Culture of resistance to transparency': Kentucky universities regularly break open records law

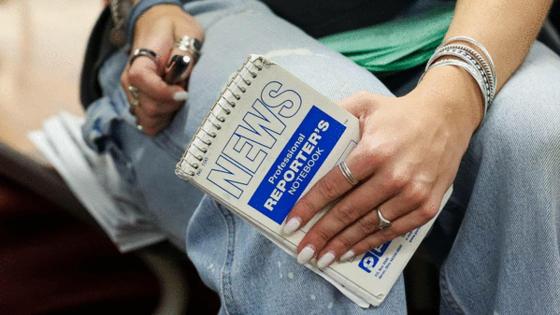

Published in News & Features

LEXINGTON, Ky. — Kentucky’s public universities routinely violate open records law, which guarantees the access and open examination of public records, a Lexington Herald-Leader analysis has found.

The Herald-Leader examined 12 years of open records and open meetings appeals filed with the attorney general’s office, reviewing 156 appeals filed from 2012 to 2024.

The newspaper looked at appeals filed relating to the state’s eight public universities, and the Kentucky Community and Technical College System as a whole. In total, Kentucky’s public higher education institutions were found to have violated the law on appeal around 65% of the time.

The analysis raises concern among supporters of “better government” and the rights by taxpayers and citizens to monitor decisions made by public officials.

“They should lead by example, rather than be the most non-compliant group of agencies,” said Amye Bensenhaver, co-founder of the Kentucky Open Government Coalition. “They have the resources, they have the knowledge base, they have the opportunity to be transparent, and they have elected to be as non-transparent as feasible.”

The Kentucky Open Records and Open Meetings Acts protects the right of citizens to be informed of what decisions public institutions make, like state or local governments and public schools/universities.

Meeting agendas, emails, staff memos, budget reports or contracts with the university are open records and can be inspected by the public. When a public institution, such as a university, denies a records request, an appeal to the attorney general can be filed to see if the institution is in compliance with the law.

The University of Louisville and University of Kentucky, the commonwealth’s largest universities, have the most appeals filed related to records. They violated or partially violated open records law slightly more than the average rate of the state’s universities, records show.

Together, those two universities account for 111 of the 156 appeals filed from 2012-2024, with 68% being found to have at least partially violated the law.

Other universities violate the law at higher rates. Kentucky State University, for instance, was found to have violated the law in all six of the appeals filed since 2012, and Northern Kentucky University violated the law in 80% of the appeals filed.

Morehead State University, meanwhile, had just one appeal filed in the 12-year period, and did not violate the law.

The types of records requested varied — some were personnel files of university employees, while others were records requested by journalists relating to specific incidents at universities.

Appeals can also be filed for a variety of reasons, from an institution not replying within the allotted time period, to the requester disagreeing with the reason for the denial.

Michael Abate, a Kentucky lawyer with expertise in open records law, said access to open records is the driving force that keeps public agencies working for the people, rather than their own private interests. Over the course of his career, Abate said universities have been some of the most frequent violaters of Kentucky’s Open Records Act.

“They’re supposed to be about the search for truth and knowledge, and about vigorous debate and openness and scholarly pursuit,” he said.

“Unfortunately, we see exactly the opposite is true.”

How an appeal works

The Kentucky general assembly passed the Open Records Act in 1976, recognizing access to documents produced, handled and maintained by government bodies and agencies, including universities, is in the public interest. Two years earlier, state legislators passed the Kentucky’s Open Meetings Act to ensure public access to meetings of public agencies.

The Kentucky Open Records and Open Meetings Acts protect the public’s right to obtain records maintained by state and local government agencies, including institutions that receive at least 25% of their funds from the government.

That includes public universities, and includes having access to meetings held by and documents used by those groups.

The open records law encourages public officials to act in the best interest of their constituents and “ensures better government,” Bensenhaver said.

“It provides an impetus for agencies to pursue the public good. It’s the idea that when you’re scrutinized and there’s oversight, you have an impetus beyond commitment to public service that impels you toward the good,” she said.

Bensenhaver served as a Kentucky assistant attorney general for 25 years, focused exclusively on the Open Records and Meetings Acts before retiring in 2016. She is a co-founder of the open government coalition, which works to preserve the rights afforded in those same laws.

In Kentucky, any state resident can request a public record, but those requests aren’t always fulfilled in accordance with the law.

When there is a dispute over decisions made relating to open records or open meetings — such as a request being denied — parties have two options: file an appeal with the attorney general, or file a lawsuit. Typically, an appeal is the first step taken.

Appeals can be lengthy, outlining the original open records request and response, along with relevant case law supporting each party’s position. Both parties in an appeal have the chance to respond and provide supporting documentation.

It’s a process that can take months if extensions are granted.

An institution can be found to have violated the Kentucky’s open records law for reasons ranging from not responding to the request in a timely manner, not properly explaining the reason it didn’t provide responsive records or simply for not releasing responsive documents.

In the Herald-Leader’s analysis of University of Kentucky cases:

—Out of 26 partial or full violations by UK between 2012 and 2024, the attorney general found the university had improperly cited exemptions under the act or failed to provide responsive records in 18 appeals.

—In the other eight appeals, the university failed to explain the reason for not providing records properly, or did not respond to the records request in the time limit set by law.

UK spokesperson Jay Blanton said UK’s open records law violations are mostly minor.

“In the majority of the cases the (Herald-Leader) cites in its calculations, the Attorney General largely affirmed UK’s positions on the major, substantive issues,” he said. “The violations cited were largely minor or technical violations as part of larger cases in which the University prevailed.”

Many of the appeals related to the University of Louisville came between 2014 and 2016, when Louisville Public Media filed two lawsuits against UofL and the UofL Foundation related to financial records, the Herald-Leader found.

UofL refused to release financial records done by an outside audit firm, Strothman and Company.

In both cases, the university and Louisville Public Media came to a settlement, and the information was released.

The foundation manages the university’s $918 million endowment and scholarships. When UofL refused to release the documents, The Kentucky Center for Investigative Reporting filed two lawsuits. In both cases, they settled and received the documents.

University of Louisville spokesperson John Karman said the university is committed to full compliance with the law.

“The university makes every reasonable effort to provide the requested records, to the extent permissible, in a thorough and timely manner and is committed to continued transparency with the Commonwealth,” he said.

University of Kentucky, Kentucky Kernel lawsuit

One of the most prominent open records lawsuits in Kentucky started as a records request in 2016, but turned into a five-year legal battle that advanced all the way to the Kentucky Supreme Court.

The University of Kentucky denied an open records request in 2016 from the independent student newspaper, the Kentucky Kernel, who requested related to the investigation of sexual misconduct by a professor. The university denied the request in full, saying the documents were preliminary, subject to attorney/client privilege and constituted an invasion of personal privacy.

The Kernel appealed, and the attorney general issued a decision siding with the student newspaper, saying the university violated the open records act by not providing the documents and not properly explaining the exemptions used to deny the request.

UK appealed the attorney general’s decision and sued the student newspaper in Fayette County Circuit Court, who ruled in favor of the university. The Kernel appealed that decision to the state appeals court in 2017, which reversed the circuit court decision and sided with the student newspaper.

UK appealed that decision in 2019 to the Kentucky Supreme Court. In a unanimous ruling published in 2021, the court upheld the appeals court decision siding with the Kernel, and ruled that UK had to release documents relating to the investigation with appropriate redactions.

“At the ripe age of 20, I discovered that I couldn’t fully trust this institution to act in my interest, much less be honest and upfront about something as critical as whether or not professors were sexually assaulting students and being allowed to move on to other universities without any recourse,” said Marjorie Kirk, the editor-in-chief of the Kernel during part of the legal battle.

Tom Miller, the attorney for the Kernel in the lawsuit, said universities have more money than people filing open records requests, so can often afford a yearlong battle in court. By the time records were given to the newspapers, the students who had requested them were long graduated, he said.

“Universities have a lot of money, and students don’t. News media has restricted budgets, employees or staff or just interested people usually have limited resources,” Miller said. “Overall, I believe that the policy is to wait out and outspend the adverse party in an open records request.”

The reason universities are willing to pay exorbitant costs: to protect their reputations, he said.

“The universities are dependent on legislative funding. They’re dependent on donor funding. They’re dependent on attracting students who pay tuition, and the disclosure of information and documentation, which is adverse to the good reputation of the university, is the issue that I think is why there’s this obfuscation of following the law,” Miller said.

Bensenhaver echoed a similar sentiment. Universities, she said, employ “destructive delay tactics” to protect their brand, often at the expense of student safety.

Blanton said it is the university’s responsibility to raise concerns when it believes responding to a request would violate someones federal privacy rights or the right for an attorney to have private conversations with a client.

“The University should be responsive. The University also should take reasonable time to carefully and thoughtfully inspect and protect records for matters of patient and student privacy,” Blanton said.

“We have a responsibility to be transparent. We work hard to do so, even as we acknowledge that we are not perfect. No process involving lots of people and tens of thousands of records likely is.”

Western Kentucky University, College Heights Herald lawsuit

Around the same time UK took its student newspaper to court, Western Kentucky University followed in those same footsteps.

In 2017, the College Heights Herald requested Title IX investigation records related to sexual misconduct allegations made against university employees. WKU responded with the number of investigations, but did not release any of the requested records.

The newspaper appealed to the attorney general, who said WKU violated the open records act and ordered them to make the documents available to the Herald.

Instead of complying, WKU filed a lawsuit against the Herald in 2017 to reverse the attorney general decision and keep the records out of the public eye.

A court battle spanning seven years ensued, ultimately ending in August 2024 when a judge ruled that WKU violated the open records act, and ordered them to give “minimally redacted” records to the student journalists.

In a statement to the Herald-Leader, a university spokesperson said WKU is committed to transparency and adheres to all applicable open records laws.

“Responding to open records requests is essential for maintaining transparency, accountability and public trust in the university,” the spokesperson said. “By providing timely and accurate access to information, the university upholds its commitment to openness while ensuring compliance with legal requirements.”

WKU was found to have partially or fully violated the law in five of the nine appeals filed between 2012 and 2024, according to the Herald-Leader analysis.

University of Kentucky, Kentucky Kernel lawsuit — again

Now, UK once again finds itself in the courtroom arguing over the disclosure of public records pertaining to a sexual assault case.

“We go through periods of time where some universities are obviously greater offenders …but consistently over time, there’s been a problem at UK,” Bensenhaver said.

The Kentucky Kernel filed a lawsuit in Fayette County Circuit Court in November 2024, after UK denied an open records request related to an on-campus rape.

Lexington Police arrested Chase McGuire for the alleged rape and strangulation of a UK student in her on-campus dorm. McGuire is not a UK student.

Shortly after the arrest, the Kernel submitted an open records request seeking a list of non-UK student guests that entered the dorm from midnight - 8 p.m. on Sept. 20, and all records on any occasion where McGuire entered a UK residential hall this academic year.

University policy requires any non-resident to check-in to the dorm.

UK denied the request, arguing the check-in log is a preliminary record, and disclosure of the log would violate the privacy rights of non-student guests.

“The Kernel believes in transparency and that the truth is crucial to the well-being of all of our students. The records in this matter pertain to the serious matter of student safety, which is why this is different than records about parking or university funds,” Kernel Editor-in-Chief Abbey Cutrer said.

“It’s concerning that UK is using exemptions that don’t apply here to withhold information that we do have a right to. Public interest in this matter outweighs the privacy concerns protecting McGuire, who was charged with rape.”

Cutrer said there is a lack of transparency at the university and, as a journalist, it’s her job to pursue the truth — even if that means a lawsuit.

Pointing out the parallels between the current Kernel lawsuit and the previous, Kirk said if there is any hope of progress in disciplining and preventing sexual abuse on college campuses, universities have to engage in public accountability.

She said there will never be a culture of accountability until there are consequences for institutions that evade the public records law.

“This culture of resistance to transparency, and honestly distrust in the public — that they cannot be given the information to act — it costs the public any ability to predict the behavior of an institution that it’s trusting their kids with, much less trusting this institution to act on behalf of them in financial, political and social issues,” Kirk said.

_____

©2025 Lexington Herald-Leader. Visit at kentucky.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments