Scientists study fish behavior during dyeing of the Chicago River for St. Patrick's Day

Published in News & Features

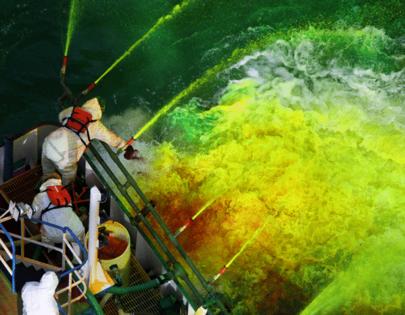

Every year as part of the city’s St. Patrick’s Day celebrations, thousands of onlookers clad in green cheer on a boat crew sprinkling orange powder into the Chicago River to turn it a festive shade.

But with the federal government considering sweeping rollbacks to environmental protections, this Saturday many may wonder: How will the bright green water affect the underwater denizens?

Last year, an extensive scientific study of fish behavior in the Chicago River system led by researchers from the Shedd Aquarium, Purdue University and the Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant offered a clue. In mid-March, as researchers studied aquatic activity they found a handful of the over 80 fish they were tracking were in the main branch downtown. On the day of the 2024 St. Patrick’s parade, none of the tagged fish rushed to find shelter from their suddenly green surroundings.

“(It) was the first time that we could actually track how individuals behave when the river is dyed green,” said Austin Happel, a research biologist at the Shedd. “We didn’t see changes in what they were doing that day, or even the next couple of days afterward, so it doesn’t seem to be causing them to be agitated.”

Since June 2023, the scientists have been following largemouth bass, common carp, bluegill, pumpkinseed, black crappies, walleyes and green sunfish, among others, with tags that ping every minute or so. These signals are picked up by acoustic receivers throughout the “Wild Mile” in the North Branch, Bubbly Creek in the South Branch and by the Riverwalk downtown, letting the scientists know how the fish respond to habitat restoration initiatives, flooding and sewage overflows, as well as seasonal changes.

St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in 2024 gave scientists a peek into the tradition’s impact on aquatic life, a matter that has concerned environmentalists since its origins in 1962.

That first year, an oil-based Air Force dye kept the water green for nearly a month, which caused an outcry. A vegetable dye has been used ever since. While its ingredients are not public knowledge, the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency has previously said the dye has no toxic effect.

Green is not the only color the river’s main branch has been tinted: It was turned blue in 2016 to celebrate the World Series champion Cubs on the day of the team’s victory parade and celebration.

Happel contrasted the unbothered behavior of some of the study’s aquatic participants during the river dispersal of dye last year to another event that made the fish they were tracking in Bubbly Creek swim for cover.

When the city of Chicago experiences very heavy rainfall, combined rain and untreated wastewater may overflow from sewage pipes and into local waterways. One such overflow happened during massive rains in early July 2023, a month into the study, and caused fish to swim to other areas where sewage had not depleted oxygen levels. If they are unable to leave the presence of a contaminant, the toxins can lead to a fish kill, or sudden death in large numbers in a specific area over a short period of time.

“A lot of our fish were moving long distances as if they were looking for a place to hide,” Happel said. “So we can contrast those. With the river dyeing, we have yet to see a fish kill associated.”

He hopes some of their tagged subjects will be in the river downtown for the Saturday celebration so the researchers can continue monitoring any possible effects of the dye on aquatic life. It would be ideal if it were the same five fish that were there last time, Happel said, because each fish, like humans, has their own personality and behavioral quirks. But it’s unlikely since the scientists can’t control where the animals decide to spend their time.

“At least, with the river dyeing, it’s always the same event,” he said. The same kind and amount of dye offers a baseline for scientists to understand the fish’s response. “It’s harder with the sewage when, each time, it’s a different amount.”

Even though vegetable dye may not have a negative impact underwater, environmentalists worry that putting a foreign substance in the river to tint it an unnatural color sends the wrong message about stewardship.

Advocates say the Chicago River is healthier now than it has been in the past 150 years. It is home to all kinds of animals, including migratory birds, beavers and turtles, as well as 80 species of fish — up from fewer than 10 in the 1970s. The system has become a natural resource for local businesses and recreation.

Environmental groups question whether dyeing is appropriate for a waterway that, despite a historical reputation of pollution, has come such a long way. Several advocacy nonprofits, including the Sierra Club Illinois Chapter, Friends of the Chicago River and Openlands, have spoken out against the tradition, arguing that the city must rethink how it interacts with the river as a signal to residents.

For instance, in 2023, what began as a joke on social media became a trend that had people dumping Mountain Dew soda in the river to mess with out-of-towners and convince them it was how Chicago dyes the water. Rogue dyers have been a problem, too, with a few cases of unsanctioned dumping of colorants into the North Branch of the river despite the presence of conservation police patrols.

“If you see one person, say, throw a piece of trash down, you’re more likely to throw a piece of trash down — or you’re more likely to care less,” Happel said. “While we like to say that the river has bigger issues to tackle before St. Paddy’s Day, the general image of dumping stuff … is not the best image of how to care for the environment.”

____

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments