California farmworkers feared 'La Migra' raids. Is Trump's deportation crackdown 'more vicious'?

Published in News & Features

Growing up in the 1970s, fourth-generation Fresnan Patrick Fontes used to pick chile and grapes in Fresno County fields alongside his grandfather as a fun way to make extra money.

Fontes, a Fresno State professor of American History, is the grandson of a Bracero worker, a controversial guest worker program that brought in an estimated four million Mexican farmworkers in the early 1940s to 1960s.

On several occasions working in the fields, he witnessed immigration agents show up in green vans and raid the workplace in search of undocumented people.

“Most of the people in the fields would run and shout, ‘La Migra!’” Fontes said. “It stuck with me all these years.”

As President Donald Trump promises to carry out mass deportations, many central San Joaquin Valley residents are on edge — especially after a surprise January Border Patrol operation in Kern County resulted in 78 arrests and dozens of deportations.

The Valley is no stranger to immigration crackdowns. Several of the region’s residents, lawyers and farmworker advocates who were active in the Central Valley during the 1960s-1980s — as well as archived Fresno Bee reporting from the era — recall a time when immigration raids were common in Valley fields and local towns.

High-profile raids led to a farmworker’s death by drowning during a Border Patrol field raid. Threats of deportations were often used to quell farmworker unionizing campaigns. Raids in small Valley towns in the 1980s involved local law enforcement and targeted people who looked Latino or Hispanic.

Trump’s focus on mass deportations has revived a debate in Fresno County and beyond about the role local law enforcement should — or shouldn’t — play in cooperating with immigration enforcement. Recent polling shows almost half of Americans support allowing local law enforcement to arrest and detain immigrants without legal status.

The central San Joaquin Valley is home to a large concentration of the nation’s farmworkers. Between 50% to 75% of California farmworkers are estimated to be undocumented.

Threats of deportations can especially impact small, rural farmworker communities, said Juan Uranga, former attorney and executive director of California Rural Legal Assistance, a legal aid nonprofit that sued the federal government over deportation practices in the 1980s.

“People have to keep in mind that it’s more than people getting deported,” Uranga said. “On top of the arrests themselves, there’s this constant message to Mexicans that they’re less than and totally vulnerable. That, at any time, at any place, people more powerful than them can swoop in and completely make a mess of their lives.”

Immigration enforcement in the fields, workplaces

After the passage of the 1975 Agricultural Labor Relations Act, California’s landmark law allowing farmworkers to form unions, Uranga said growers, labor contractors and others in power used the threat of calling immigration officials as a “weapon” to keep farmworkers from organizing.

“Even if growers didn’t call on the INS, Latinos knew that growers had the capacity to do that,” he said. INS used to oversee the Border Patrol and is the predecessor to what is known today as U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE.

Humberto Gomez, a retired United Farm Workers organizer, said that raids happened frequently in the late 1960s to early 1970s — around the time the UFW started its strikes. But they returned in the 1980s, he said.

“In the ‘80s we had a lot of raids,” he said in Spanish. “They hit us very hard.”

To protect workers during workplace raids, Gomez said the union got creative. When immigration officers would show up to the fields, workers who had legal citizenship would run, while undocumented workers stayed back picking crops, Gomez said. The idea was that usually workers without papers were expected to flee at the sight of officers.

Another concern for Gomez during workplace raids was the risk of drowning.

“We didn’t want anyone to fall into rivers or canals during a raid. Many people don’t know how to swim,” he said.

In March 1985, Alvaro Dominguez Gutierrez, a farmworker, drowned in the Kings River during a series of raids near Kingsburg in which 80 people were rounded up. He was the 14th undocumented foreign national to drown in California since 1974, according to a March 1985 Fresno Bee story.

Border Patrol agents arrived at the orchard Dominguez Gutierrez was working at and started chasing a group of workers, The Bee reported. Frightened, Dominguez Gutierrez also started running with another group of workers through water about three-feet high. He then stepped into a hole and drowned, likely because he didn’t know how to swim, officials said. (INS later said the drowning was a “tragedy” but not Border Patrol’s fault.)

“The technique they would use was basically to force people into an irrigation ditch or into a body of water,” Steven Rosebaum, a former staff attorney for CRLA who called for an end to field raids, said in an interview.

1980s raids in Fresno County bars prompt lawsuit, policy changes

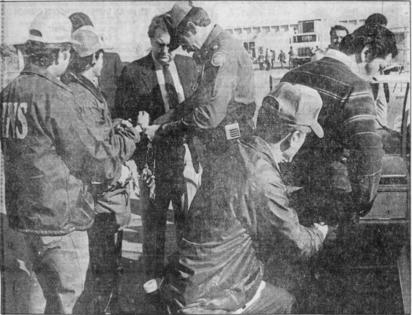

In September 1984, members of Sanger police, Fresno County Sheriff’s Office, California Highway Patrol and INS/Border Patrol used helicopters, floodlights and barricades to blocked off several streets in town and descended into 16 bars to arrest undocumented people.

According to a Jan. 17, 1985 Fresno Bee story, 255 individuals were deported as a result of the operation, and 40 more were arrested with a variety of charges.

Fresno civil rights activist Gloria Hernandez, who worked for CRLA at the time, said she was “pissed” when she learned of the raids.

“One of the (raided) bars that they went to is one that I used to go with my sister and brother-in-law. We’d dance and have a good time,” she said in an interview. Hernandez alerted CRLA’s legal team about getting involved in the case.

Among those detained during the operation were Sanger resident and Korean War veteran Tony Velazquez and his wife, Sallie. The couple was detained for several hours in a Sanger bar during the raids, according to a lawsuit filed the following year by CRLA.

“They were forced to sit down with their legs open and (weren’t) able to get up until they proved their citizenship,” Hernandez said. (Velazquez’s family members declined to comment on this story.)

The high-profile raids were controversial because they involved local law enforcement and because immigration officers detained “everyone with brown skin who could not prove they were citizens,” according to a Nov. 17, 1985 Bee story.

A similar operation targeted in Parlier bars on April 6, 1984, resulting in the deportation of 170 Mexican nationals, according to Bee archives. “They knew that the campesinos went to the bars for a while on Friday and Saturdays,” recalled Gomez, a Parlier resident.

After Fresno County Board of Supervisors rejected a multi-million dollar claim in connection to the Sanger raids, CRLA sued the INS in 1986 on behalf of eight individuals arrested during the raids. They alleged their civil rights were violated by INS and Border Patrol agent when they were detained without reasonable cause or warrants.

The lawsuit, known as Velasquez v. Senko involved eight separate immigration raids in Gilroy, Salinas, Calistoga and Watsonville that happened in the early 1980s.

“As part of an alleged pattern and practice, the defendants target predominantly Hispanic towns, neighborhoods, and businesses for warrantless dragnet searches and seizures of suspected illegal aliens,” the suit said.

The lawsuit was dismissed in 1992 after the parties agreed to settle. The settlement included a ban on joint raids in the Valley for ten years, said Hernandez.

The 1980s raids prompted a wave of activism and local policy changes.

Sanger City Council issued a resolution opposing raids and pledging that “Sanger officers would not be used to round up illegal aliens in the future,” The Bee reported in January 1985.

Fresno City Council voted in April 1985 to prohibit Fresno Police from participating in Border Patrol raids, according to The Bee newspaper archives.

For Uranga, the main difference between the 1980s and now is that elected officials in California are keen on protecting immigrant rights, he said. Whether local jurisdictions can get away with anti-immigrant actions depends on state action.

“We didn’t have that kind of political support (back then),” he said.

What’s next?

Over the years, raids as a means of enforcement became “frowned upon,” Rosenbaum, now a UC Berkeley law professor, said in an interview.

Raids in the Valley ended up slowing down in the 1990s and 2000s as they became politically unpopular, Rosenbaum said.

“The raids, you know what, it just didn’t look good,” he said. Democrats didn’t like them and Republicans like Reagan and Bush were of a “softer and gentler Republican Party.”

A shift in priorities after the 9/11 attacks also played a role. Border Patrol closed down its local offices in Fresno, Livermore and Stockton in 2004 and as the federal government shifted its focus to enforcing immigration at the border, The Bee reported at the time.

Two decades later, Trump in his second term has embraced a “rage policy” that champions and highlights raids as a tactic to enforce immigration, Rosenbaum said.

He called today’s immigration crackdown under Trump “more focused and more vicious than 40 years ago.”

The new administration’s rhetoric around immigration has revived a debate about the role of local law enforcement in immigration enforcement – which was a hot topic when the sanctuary city movement took hold in the 1980s, Rosenbaum said.

Last month, Fresno County Sheriff John Zanoni criticized a 2018 state law that prohibits local law enforcement from cooperating with immigration officials. Last week, a Sacramento area sheriff said he’d work with ICE in certain circumstances “even if I’m not supposed to.”

Hernandez said young people today are protesting against inhumane immigration enforcement tactics. She credits decades of activism for laying the foundation, particularly the wave of Latino activism after the passage of the 1993 anti-immigrant Prop 187 in California. The initiative sought to prohibit undocumented immigrants from accessing state services, including public education and health care.

“I think the groundwork we laid in the ‘80s, ‘90s, has raised awareness. I think people are mad. The young ones are mad,” she said. “They’re saying, ‘no, we’re not going to allow this to happen.’”

©2025 The Fresno Bee. Visit at fresnobee.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments