Students as pawns? SC school choice, voucher debate to return, bring about emotions

Published in News & Features

COLUMBIA, S.C. -- Beth Martyn came with 19 people to see the legislative process. Martyn, the principal at Divine Redeemer Catholic School in Hanahan, and those families wanted to show their support for a bill to allow public money to go to private schools, this time using lottery revenue instead of tax dollars.

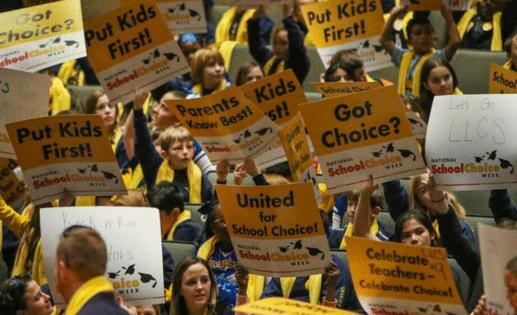

Martyn’s group, which included students and parents, says it’s not there to pull at heartstrings.

“(It’s) more about showing lawmakers the real people who are affected by these decisions,” Martyn said referring to a recent state Supreme Court decision on the state’s educational scholarship account program.

The fact that a group of that size would be among the people packing a December subcommittee meeting when the Legislature isn’t in session underscores the passionate battle that lies ahead when the legislative session begins this month.

The Republican-controlled state legislature favors letting parents use public money to send their children to private schools if they want, but public school advocates say too little money goes to public schools now, and diluting it further will only cause more harm and benefit private schools with no accountability.

Public school advocates won a reprieve in September when a state Supreme Court decision struck down the private school portion of the GOP-supported proposal, but lawmakers have a new plan they want to push through — using lottery money instead.

A move to lottery revenue

A move to use lottery revenue to pay for the educational scholarships in kindergarten through 12th grade would require using state tax dollars in the state’s general fund to pay for lottery-covered expenses such as school buses and college scholarships, which students can use at the state’s public universities, as well as at private colleges in South Carolina.

Revenue from the lottery comes from money people choose to spend when they play as opposed to money people are required to pay through taxes.

Still, while the college scholarship program has not had any legal challenges, such a plan would almost certainly be challenged. And possibly unpopular.

“You didn’t sell the lottery to the people of South Carolina on ‘we could fund private school vouchers with it,’ ” Sherry East, South Carolina Education Association president, said. “I don’t know how the public would feel about that.”

Potentially complicating the proposal in the long run is the drop in revenue the South Carolina Lottery has seen in recent years back to pre-pandemic levels, according to figures from the Revenue and Fiscal Affairs office:

▪ 2020-21: $612.1 million

▪ 2021-22: $568.7 million

▪ 2022-23: $605.4 million

▪ 2023-24: $602.7 million

▪ 2024-25: $538.2 million (estimated)

▪ 2025-26: $502.7 million (estimated)

The lottery saw record revenues during the 2020-21 fiscal year because of COVID lockdowns and stimulus funding, according to lottery spokeswoman Holli Armstrong. Otherwise, the lottery is often dependent on of huge jackpots to drive increased ticket sales.

Pawns in a political fight?

Public school advocates just want to defend public education, according to East, of the South Carolina Education Association.

“We’re trying to protect the integrity of our public schools and keep them whole,” East said. “So anytime you take a nickel or dime away from it, or millions of dollars, we get a little frustrated by that.”

East said using public money toward private K-12 schools is part of an agenda pushed by national Republican Party.

“Let’s call it what it is. It is a voucher program that is highly pushed by the national politics of the Republican Party and our guys want to say they have checked off the box,” East said.

East took a swipe at the presence of Martyn’s group at the subcommittee hearing, saying children were being used as political pawns instead of being in school learning.

But Martyn, the principal at Divine Redeemer, said families attending these hearings is about seeing how advocating for their goals works, at least in the state capital.

State Superintendent of Education Ellen Weaver, a longtime school choice advocate, said she applauds students who speak for themselves, in part because she believes students have different needs and a “one-size-fits-all” approach is not effective.

South Carolina lawmakers have been trying to expand school choice. In recent years, they approved an educational scholarship account program for low-income students, which allows students to take the $6,000 in state money allocated to a public school and spend it on another school.

Money could be used for tuition, tutoring or transportation among other education-related expenses. Lawmakers allowed students to use the money at private schools, but the state Supreme Court struck down that portion of the law because of a provision in the state constitution that says public money cannot benefit a religious or private school.

Before the state Supreme Court decision, the House last session passed a bill to expand the educational scholarship program to any South Carolinian, instead of just low-income students. The bill did not move in the Senate last year.

A possible solution would be to amend the constitution. But in South Carolina that requires a referendum be put in front of voters and couldn’t take place until 2026.

Placing a question in front of voters would be a risk, because despite South Carolina being a Republican state, voters may buck legislators’ goals.

In 2024, voters in Kentucky and Nebraska, states that voted for President-elect Donald Trump, rejected measures that would have allowed public money to go to private schools.

State Sen. Greg Hembree, R-Horry and the chairman of the Senate Education Committee, conceded going the constitutional amendment route is an option, but allowing lottery money to be used now can be carried out more quickly.

He said the provision in the state constitution that blocks public money from religious or private schools is a relic of the past and said it was a “bad idea” to leave it in the state constitution.

“It was an intentionally discriminatory constitutional amendment when it was crafted to discriminate against Catholics,” Hembree said.

The fight grows tense

It is possible, maybe even likely, the debate will turn uglier as decisions get closer.

Aside from the emotions, the issue is drawing intense interest, and cash, from interested parties.

“Lobbyists are spending a lot of money on making it an issue,” said Derek Black, a professor at the University of South Carolina Joseph F. Rice Law School. “I don’t mean that in a pejorative sense. I mean that in a factual sense.”

In November, a GOP political operative posted on X that Hembree was “an impediment” to universal school choice and threatened to release embarrassing information if it failed again. The post raised questions about the tactics advocates would be willing to use and also spotlighted the increased pressure GOP leaders will be under to deliver.

The operative, Chris Slick, later removed the post, saying it was “stupid for me to do. I learned my lesson.” Slick added he had nothing to embarrass Hembree with. Hembree, for his part, dismissed the post as not worthy of his attention. A source with the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division, asked if it such a threat crossed legal boundaries, said it would not look into the matter.

As for public school advocates, Black says they are just defending something they believe in.

“There’s a lot of screaming and yelling, as well ... I would characterize that as ‘stop trying to hurt me,’ ” Black said. “’Why are you trying to tear us down and build something different.’ That is the perception we could talk about. Whether that’s reality or not reality, but there is that perception. ‘We didn’t start this fight, we’ve been drawn into a fight where we’re just trying to protect ourselves.’ ”

____

Reporter Anna Wilder contributed to this article.

©2025 The State. Visit at thestate.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments