Key trauma center in Haiti goes up in flames after gangs attack with Molotov cocktails

Published in News & Features

Haiti’s only neurological trauma center for nearly 12 million people, an 87-bed hospital tucked down a narrow street off the airport road in Port-au-Prince, survived a powerful 2010 earthquake, a deadly coronavirus epidemic, kidnappings and, until this week, the gang violence that had forced many of the capital’s doctors and nurses to flee abroad.

On Monday, however, Bernard Mevs Hospital in Port-au-Prince could not survive the Molotov cocktails.

Criminal gangs armed with the homemade explosives attacked the medical facility, setting fire to an ambulance and other vehicles in the courtyard along with millions of dollars worth of life-saving equipment. Two CT-scanners, a brand-new 3D X-Ray imaging machine, the lab, operating rooms and the pediatric ward all went up in flames.

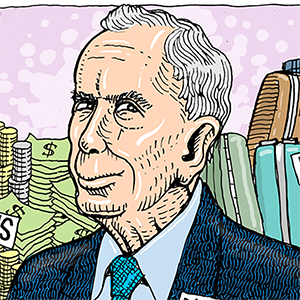

The office of physicians Marlon and Jerry Bitar, the twin brothers who founded the small hospital and who had a long partnership with the University of Miami, was also trashed, according to a video shared with the Miami Herald by Dr. Barth Green, a retired world-renowned neurosurgeon whose Miami-based Project Medishare has been a leading financial supporter of the hospital.

“It’s a very sad day,” said Green, who co-founded Project Medishare in 1994 with Dr. Arthur Fournier to help Haiti deal with its health crisis and has helped raised millions of dollars for Bernard Mevs in donations, equipment and free care. “Talk about biting off your nose to spite your face: These gangs don’t realize that this is the one place where the gangs and the police and the Kenyans and the bourgeois and poor people, all are welcome if they have trauma.”

The hospital had been recently emptied of all of its patients. But as recently as late August it was caring for police officers injured in the line of duty and received a visit from Police Chief Rameau Normil, who had accompanied the prime minister at the time, Garry Conille, and journalists.

In addition to its adult, pediatric and neonatal intensive care units, the hospital had multiple residency programs where it trained doctors and nurses, and offered Haiti’s only neurosurgery residency program.

“This makes me worried right now, because even the littlest, the smallest things like an appendicitis, a ruptured appendix, where do we go to to get operated? We’re literally back to zero right now,” said Harold Marzouka Jr., a local businessman who has financially supported the hospital for the past decade.

Most of the capital’s hospitals, including the largest public medical facility known as the General Hospital, are overrun by armed gangs and if they are not, then getting to them requires money or traveling through gang territory.

Bernard Mevs “was almost like the pillar with all of these; we would treat the more critical patients and the critical care, and then we could move them off to some of these other places where they would go to recover, and then go home because those places don’t treat the kind of cases that we’re doing, like these really complicated procedures,” Marzourka said. “We’re small, but we’re muscular.”

Devastated after the attack, the Bitars had spent most of the morning in Marzouka’s office. They did not respond to the Herald’s request for comment. Early Tuesday Marzouka tried to send a truck to the facility to see if any of the equipment, especially in the operating rooms, could be salvaged. The area, he said, had become a war zone and police said it could not be accessed.

“The international community is watching the deterioration of a nation and doing nothing about it,” Marzouka said. “It’s as if you’re looking at a sinking ship with people on it, and you’re on the ship next to it, and you’re just looking at the people drowning. That’s literally what the picture looks like. You have a ton of life vests on your ship, and all you have to do is toss them out, and you’re not even doing that.”

The threats against the hospital started two weeks ago. In that time, staff were able to relocate the few patients in the facility. On Sunday, several sources said, gangs tried to breach the facility by breaking through a wall but were pushed back by police.

The gang returned Monday and despite police putting up an hours-long fight, the bandits still managed to set the blaze, sending up 30 years’ worth of work and dreams into smoke.

Green, who boosted support for the hospital after the 2010 earthquake and had been following events closely, said the gangs wanted a bribe.

“They said, if you don’t give us cash, then we’ll burn it down,” he said. “And so that’s what they did.”

The destruction leaves Haitians with fewer options. Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières, which offers some trauma care, is still only partially open after closing for 22 days following attacks by police against its staff. The General Hospital, the largest public hospital, also remains closed after gangs launched coordinated attacks to bring down the government of then Prime Minister Ariel Henry. Henry, a neurosurgeon, had spent years saving lives at Bernard Mevs and still performed surgeries until he was forced to resign by the United States and the Caribbean community in March.

Three years ago Project Medishare built a trauma center, similar to Miami’s Ryder Trauma Center nearby, but Green said they’ve been unable to open the facility due to the spreading gang violence.

“The sad thing is that our government, the Biden administration, is pouring billions of dollars into countries in the Mideast and Ukraine, where not a fraction of the people are raped or killed or murdered every day” as they are in Haiti, Green said.

“I am sad to be an American. I really am; all it would have taken is one naval ship, one Coast Guard ship to pull into Port-au-Prince, into the port, and the gangs would start to pull back and then just put one or two platoons of Marines or Navy Seals on the ground, and the gangs would quickly disappear,” he said. “But that’s too much for America. They’d rather just count the bodies and it’s, in my opinion, racism and it’s just tragic.”

Administration acknowledges Haiti challenges

The administration has provided Ukraine with $100 billion in aid, the State Department’s Tom Sullivan told journalists on Tuesday in a media call highlighting the administration’s foreign policy achievements. Though he did not talk specifics about Haiti, Sullivan acknowledged the country’s security and governing challenges.

“The security conditions there remain incredibly fraught. The suffering that the Haitian people continue to experience at the hands of gangs, and the overall lack of governance in the country on a day-to-day basis, is incredibly alarming to us,” Sullivan said. “That’s why we work so hard to stand up the multinational security support mission that the Kenyans are leading, to provide partnership with the Haitian National Police to try and restore order.

“This remains a work in progress,” Sullivan added, noting that the administration anticipates that the current 416 foreign officers in Haiti will be augmented in the coming weeks.

Dennis Hankins, the U.S. ambassador in Port-au-Prince, told Haiti ‘s Le Nouvelliste newspaper over the weekend that an additional 600 security agents from Kenya, the Bahamas and Guatemala are expected to arrive before the end of the year as long as planes can land. The capital’s international airport recently reopened after armed gangs fired shots at three U.S. airlines last month, but the Federal Aviation Administration has expanded a ban against U.S. carriers flying into Port-au-Prince until March.

The lack of hospital care in Haiti is becoming increasingly critical: More than 700,000 are internally displaced and more than 5 million are going hungry. Meanwhile, few hospitals in the capital are functioning while those outside are increasingly overwhelmed.

Marzouka said he can’t believe where things have ended. He personally got involved with Bernard Mevs after surviving cancer and realizing that, unlike most Haitians, who don’t even have access to a cancer-fighting radiation equipment in the country, he survived because he was able to travel to the U.S. for treatment and had international insurance. Today, he shudders as he thinks of what most Haitians are facing.

“People are dying from the most basic needs, like diabetes medicine, insulin,” he said. “It’s the saddest thing that someone could be witnessing in today’s time. We’re literally 700 miles away from the U.S. coast, and it’s something that we can fix in a second. I have to believe that this issue with the gangs … goes way beyond a political issue.”

_____

©2024 Miami Herald. Visit miamiherald.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments