Boeing CEO's message to Senate: We made mistakes and learned our lesson

Published in Business News

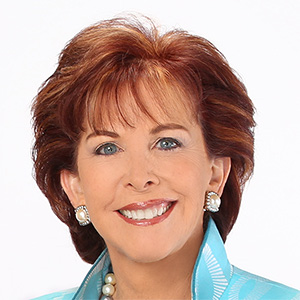

Boeing CEO Kelly Ortberg came to Congress Wednesday with a straight-forward message: Boeing has made “serious missteps” in recent years but it has a promising improvement plan guiding it forward.

Lawmakers, in response, said they want to see the airplane manufacturer succeed but are still concerned about some of the practices in place at the company’s factories and in its board room.

Some said they appreciated Boeing’s efforts to encourage employees to come forward with safety concerns but worried about allegations of retaliation when workers did so. Others asked for more details on ensuring a stable production process that won’t let manufacturing defects slip through the cracks. Still others worried about the Federal Aviation Administration’s oversight, and steps by the regulator and Boeing that may hand more certification authority back to the manufacturer.

Ortberg, who testified Wednesday morning before the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, was adamant that Boeing was committed to ensuring quality and safety were at the forefront of its operations.

“Look I want to be clear, I’ve not provided financial guidance to Wall Street for the performance of the company, I’ve not provided guidance on how many aircraft we’re going to deliver, I’ve gone and gotten financial coverage so that we can allow our production system to heal,” Ortberg said. “I’m not pressuring the team to go fast. I’m pressuring the team to do it right.”

Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, and chairperson of the Senate Commerce committee, called the hearing in February to examine steps Boeing has taken to address safety and production concerns after a harrowing safety incident in January 2024. That month, a panel blew off a Boeing 737 MAX 9 plane shortly after takeoff, leaving a hole in the side of the plane.

The company had already faced heightened scrutiny after two MAX 8 planes crashed in 2018 and 2019, killing 346 people. After an 18-month grounding, “many had hoped the worst was behind Boeing,” Cruz said at the start of the hearing Wednesday.

But the panel blowout “produced fresh doubt about Boeing’s ability to safely build planes,” Cruz continued. The company had cut corners in production to move quickly, lacked adequate internal auditing processes and “created an unsustainable lack of safety culture.”

On Wednesday, Ortberg reiterated much of what Boeing has said before: It has made lasting changes that will lead to a better Boeing.

“No one is more committed to turning our company around than our team,” he said.

Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Washington, and ranking member of the Senate commerce committee, said after the hearing that Ortberg “delivered a welcome change in tone” when it comes to safety at Boeing.

“The new Boeing CEO said he has been spending his time listening to employees, customers, affected crash victims’ families, the FAA, aviation experts and transportation inspectors,” Cantwell said. “It shows.”

The path forward

Boeing’s changes following the panel blowout have focused on four areas: reducing the number of defects as aircraft move through production, enhancing employee training, simplifying procedures and elevating safety and quality culture.

To reduce defects, Boeing has implemented a “move ready” process that discourages moving a plane forward in the factory if there are still unfinished jobs. If there are leftover tasks, Boeing will perform a safety risk assessment to determine if the unfinished work could pose a safety concern down the line.

Of the 800 safety risk assessments it has performed, Ortberg said Boeing has chosen to keep planes in place 200 times.

The company is gearing up to implement a mandatory safety management system, or SMS, a systematic way of measuring risk and ensuring safety is baked into procedures.

It has been operating under a voluntary SMS already but hopes to have the updated system in place by October, Ortberg said.

Ortberg also said Wednesday that Boeing has increased data collection for planes in-service to “pay attention” to how they are being operated and maintained.

In his opening remarks, Ortberg acknowledged Boeing’s position in the U.S. economy as one of the nation’s largest exporters and as a key manufacturer for defense systems. Boeing recently won a contract to build the U.S. Air Force’s next generation fighter jet— the F-47.

“This commitment to aviation safety goes well beyond Boeing,” Ortberg said. “It all depends on us getting this right.”

A culture shift

Culture is the “predominant change we are making as a company,” Ortberg said.

To make that change, Boeing leadership will spend more time listening and learning from employees and holding other leaders accountable, he continued, adding that he believed past leadership perpetuated the problem by “not exhibiting those behaviors that are on a poster.”

In a shift from past executives, Ortberg moved to Seattle when he took the top job because “I believe our leadership needs to get closer to the people designing and building our aircraft,” he said.

Critics of Boeing agree that the company needs to make substantial changes to its culture, including how it handles employee concerns about quality and safety practices. David Boies and Sigrid McCawley, attorneys who are representing the family of a Boeing whistleblower who died by suicide, said in an interview ahead of Wednesday’s hearing that Boeing has yet to take responsibility for the missteps that led to the fatal MAX crashes and the panel blowout.

“I don’t think that they’re going to make real progress until they’re prepared to accept that the old culture was wrong. They can’t have it both ways,” Boies said. “Thus far, they’ve been trying to ride two horses — one saying it’s really a new Boeing and we’re on top of it, but on the other hand, trying to defend what happened in the past.”

Employee feedback

Though Boeing has set up new avenues and strengthened existing systems for employees to report concerns, lawmakers pressed Ortberg on taking more action to incorporate employee feedback in high-level decisions.

Sen. Cruz spoke directly to Boeing employees, telling them to “consider my door open” if they wanted to discuss how “Boeing is turning a corner.”

Sen. Ed Markey, D-Massachusetts, even introduced the possibility of new legislation to require Boeing to put an employee representative on its board of directors. Right now, the board includes financial professionals and though Boeing says it has members with safety experience, Markey pointed out that experience isn’t in the aviation industry.

In response, Ortberg said “having a diverse set of inputs helps us think through and benchmark” best practices from other industries.

Markey disagreed with that philosophy. “There has to be a particular expertise about the aerodynamics that are at the heart of your industry,” he said. “There’s no way that these board members should qualify as safety experts.”

“Safety must be in the room. Expertise must be in the room.”

Concerns over self-certification

The day before the hearing, Cantwell, the ranking Democratic member of the commerce committee, raised “critical concerns” about a program that allows Boeing to certify its own work.

That program — called Organization Designation Authorization, or ODA — has been heavily scrutinized over the past several years, and has been portrayed as allowing Boeing too much control of its own oversight. Critics say the FAA, the regulatory agency tasked with overseeing quality and safety of airplane manufacturers like Boeing, has been too lax with its mandate.

Cantwell sent a letter Tuesday to the FAA’s acting administrator Chris Rocheleau urging the agency to address those concerns before deciding next month whether to renew Boeing’s authorization.

On Wednesday, Ortberg said Boeing has made changes to its ODA program already, including adding an ombudsman so Boeing employees performing FAA tasks have someone to report concerns to and making sure those workers don’t worry about the impact of their decisions on internal performance reviews.

Cantwell indicated that the FAA had fallen short of its mandate, even after being notified of concerns from the National Transportation Safety Board.

The Senate committee is “getting a big sense that the NTSB makes recommendations and the FAA kind of ignores them,” Cantwell said.

Sen Tammy Duckworth, D-Illinois, pressed Ortberg for a commitment that Boeing would not seek or accept oversight authorization from the FAA until it had fixed concerns about its ability to properly regulate the aircraft manufacturer.

“It will be up to Boeing to decide whether to accept that delegation of responsibility,” Duckworth said. If Boeing chooses to accept, that would “look like Boeing is taking advantage of a hobbled regulator,” she continued.

Ortberg responded that it worked transparently with the FAA and would support providing whatever information the agency needs to address concerns with its oversight.

The MAX crashes

In a nod to whistleblowers who are still raising alarm bells about practices inside Boeing, Cruz asked Ortberg if he believed a manufacturing error could have contributed to the fatal MAX accidents six years ago.

Regulators have attributed the crashes to an engineering flaw and an error with what was then a new software system, known as the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS. But whistleblowers have alleged as recently as last year that there may have also been manufacturing defects with electrical wiring that caused a sensor to fail, triggering the MCAS system that ultimately caused the planes to nosedive.

Ortberg said Wednesday he was “not aware of any electrical wiring issues” and reiterated that the “cause of the crash was the MCAS design.”

“MCAS has been redesigned and design changes have been incorporated in all aircraft,” he said.

Another safety concern

Lawmakers used the hearing as an opportunity to discuss another harrowing plane crash, though this one didn’t involve Boeing. In January, an Army helicopter collided with a Delta Airlines plane as it approached Ronald Reagan National Airport near Washington, D.C., killing 67 people.

In the weeks since the crash, Cruz and Cantwell have asked the U.S. Army to provide more information about a surveillance system on the helicopter meant to help other aircraft and air traffic controllers track its position. In the January crash, the Army helicopter had that system turned off.

Last month, Cruz and Cantwell sent a letter to Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth requesting a memo from the U.S. Army on its use of the system in the national airspace. The army had yet to send that memo to Congress as of Wednesday morning, Cruz said in his opening statement at the hearing.

“It begs the question,” Cruz said, “What doesn’t the Army want Congress or the American people to know about why it was flying blind to the other aircraft or air traffic control.”

©2025 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments