Bird flu infected California cows. Why didn't milk prices spike like egg costs did?

Published in Business News

Bird flu outbreaks sent egg prices soaring in recent months, in some cases north of $9 per dozen. While the virus also spread to dairy cattle, the outbreaks didn’t seem to boost California milk prices.

A group of UC Davis economists recently wrote that though California produces more than 15% of U.S. milk, bird flu has had “little or no impact on milk prices.”

Their assessments were released in a recent edition of the Agricultural and Resource Economics Update, a publication by experts in the University of California system.

The economists estimated that the flu has likely affected herds producing roughly 90% of California milk. But critically, they wrote, most California milk is used for products that can be stored for a period of time, like cheese, butter and whey.

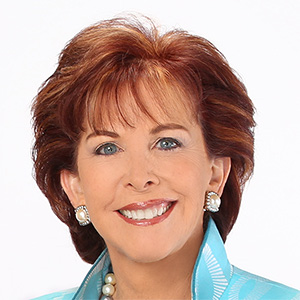

“It’s essentially industrial raw material,” said Daniel Sumner, a professor of agricultural economics at UC Davis, and one of the authors of the analysis.

Even a 10% dent in California milk production, the economists wrote, didn’t hinder the global market for those processed products.

People might accept a price hike to buy specialized milk or cheese from a small farm with a few hundred cows, Sumner said. But for the broader market, California competes with other dairy states and international producers like New Zealand, Australia and Ireland, which makes it difficult to raise prices.

“There are roughly 1,000 commercial dairy farms in California,” Sumner said. “If one of them said, I think I’ll charge 10% more for my milk, they would not sell a drop.”

There are other factors, Sumner continued. The California egg market may have been especially volatile because of the state’s rules around cage-free eggs. There are also few widely-used substitutes for eggs, and many for beverage milk. And the infections affect chickens and cows differently.

While the virus spreads readily among dairy herds and poultry flocks alike, most infected cows can recover with veterinary attention, while most birds die quickly, California Department of Food and Agriculture spokesperson Jay Van Rein said in an email.

Regardless, Sumner said, responding to an outbreak is an expensive ordeal for a dairy farm.

“The bottom line for California milk producers,” the economists wrote, “is that production is down, costs are up, and prices will not compensate for those losses.”

©2025 The Sacramento Bee. Visit at sacbee.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments