How cuts to the federal consumer protection agency could affect Georgians

Published in Business News

Over the past few weeks, the Trump administration has set its sights on another federal agency it believes needs to be culled, aiming to curtail the work of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

From trying to get medical debt off credit reports to going after a student loan servicer, the work of the CFPB has touched many aspects of Americans’ lives. But its critics say the bureau lacked oversight, exceeded its authority and its work sometimes had unintended consequences.

The CFPB was created in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis by the Dodd-Frank Act to oversee consumer finance companies. Since its establishment in 2011, the bureau says it has provided nearly $20 billion in consumer relief to Americans targeted by harmful financial practices. Under the Biden administration, the CFPB recently issued a rule requiring medical debt be taken off credit reports.

The CFPB’s work in Georgia has covered an array of industries. More than 300,000 Georgians have received payments from the CFPB’s victim relief fund, totaling nearly $150 million as of last October. The bureau announced in December it would refund more than $103.5 million to Georgians who were charged junk fees by a group of credit repair companies.

Beyond fees, the CFPB has gone after Gwinnett-based U.S. Auto Sales over its practice of misusing kill switches in the cars it sold and other alleged misconduct.

The administration began targeting the CFPB in early February. Soon after President Donald Trump named Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent acting head of the CFPB, Bessent ordered much of the work of the bureau be stopped, according to The New York Times. Then on Feb. 7, Trump passed the acting duties to Russell Vought, the new White House budget director and a chief architect of the conservative Project 2025 plan. Elon Musk, the head of Trump’s government cost-cutting measures, posted on X that same day: “CFPB RIP.”

In the days following Vought’s appointment, he asked the Federal Reserve not to distribute the CFPB’s next draw of funding, closed the CFPB’s Washington headquarters and told its approximately 1,700 employees not to do any work. The bureau’s homepage now shows a 404 error.

The CFPB set up a tip line for companies to report on any of the bureau’s enforcement or supervision staff who were working despite Vought’s stand-down order. Officials have also laid off more than 100 CFPB employees, according to reports. But on Wednesday, Trump nominated Jonathan McKernan, a former board member of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., to a five-year term as head of the CFPB.

Despite that move, it’s clear the administration’s moves against the CFPB are “really trying to shut it down,” Anton Becker, communications director for the financial watchdog group Better Markets, told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

“This was an agency created by law for a reason after the financial crisis, and … they’re halting enforcement, they’re halting rulemaking,” Becker said.

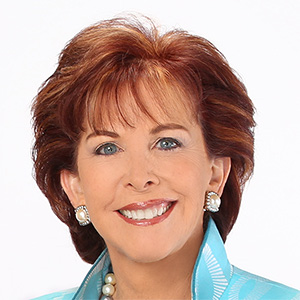

Georgians stand to “lose a lot” if the CFPB is shut down, said Liz Coyle, executive director of the nonprofit consumer advocacy organization Georgia Watch, pointing to the recent junk fees settlements and the medical debt rule.

“Georgia (is) one of the states most impacted by the devastating problem of medical debt on credit scores and medical debt, period,” Coyle said. “People don’t go to a hospital and say, ‘I’d like to borrow $100,000 to save my life.’ So that rule is so important to so many Georgians.”

The medical debt rule was set to take effect March 17, but a judge pushed back the rule’s effective date by 90 days after a CFPB request in early February.

Jerome Powell, chair of the Federal Reserve, said during a hearing Tuesday that there would be a gap in enforcement for the banks the Fed doesn’t supervise if the CFPB is shut down.

But some experts outside of the administration see the potential CFPB shutdown as a positive thing.

“I don’t think the average American is going to feel it, certainly not in the short run and potentially not even in the long run,” said Joseph Mason, an economist and fellow at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business.

He worked for the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency from 1995 to 1998 and said it, along with other agencies, played a role in consumer enforcement. He thinks the CFPB has engaged in “mission creep” and some of its efforts have led to unintended consequences, like a crackdown on personal credit card marketing pushing companies to more widely market business credit cards, which have fewer protections.

“I’m sympathetic to consumer finance, but in my opinion, the CFPB hasn’t worked from the start, and I think that the administration is right about that,” Mason said. “Now, is the answer to rip it all out? I don’t know, we’ll see. But certainly, questioning the existing construct, I would argue, is correct.”

But civil rights groups, consumer finance watchdogs and employee unions are challenging the administration’s moves in court. Coyle from Georgia Watch served on the CFPB’s consumer advisory board during the first Trump administration and said attempts to weaken the agency didn’t work then, adding the courts have consistently ruled in favor of the CFPB continuing as intended by law.

She noted Musk and the Department of Government Efficiency is “unprecedented,” but said she expects the work of the CFPB will continue.

“There will be changes, but the actual functioning of the bureau, I believe, will continue per the law that created it.”

©2025 The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Visit at ajc.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments