'Marijuana recession' threatens Denver's fledgling cannabis delivery businesses

Published in Business News

The day before Thanksgiving, Michael Diaz-Rivera was delivering goods to customers in the snow and cold, more focused on “Green Wednesday” than Black Friday.

Diaz-Rivera, who contracts with Denver cannabis stores, figured he and his drivers could end up making about 25 deliveries if people chose to stay inside for the day. And Green Wednesday, the day before Thanksgiving, is typically the second-busiest day of the year for the cannabis industry, he said.

The busiest day is April 20, or 4/20, the unofficial marijuana holiday long before it was legalized by states across the country.

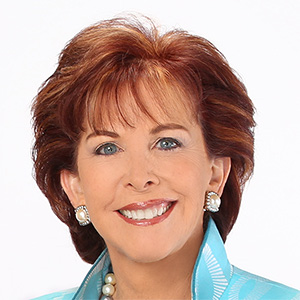

Diaz-Rivera relished the prospect of a full day ahead. He started Better Days Delivery Service in January 2021 and began expanding his business around the time that marijuana sales in Denver and Colorado began dropping. Grants and technical assistance from city and state programs have helped him and others with the challenges the industry is facing.

“I already applied for a grant again this year. If I don’t get it, my chances of staying in business are less than likely,” Diaz-Rivera said. “But I’m fighting to stay alive.”

City officials are concerned about the impacts of the so-called “marijuana recession” on the fledgling delivery business, tailored to give people from disadvantaged backgrounds or with past marijuana violations an opportunity to enter the industry.

Denver’s licenses for cannabis delivery businesses are permanently restricted to people who qualify under the city’s social equity program. Diaz-Rivera was eligible because he grew up in a low-income area and was convicted of felony possession of marijuana in 2006.

“What we’ve really been focusing on for the past few years in Denver is trying to bring more equitable access to the industry,” said Eric Escudero, spokesman for the city Excise and Licenses office.

The city’s social equity guidelines also apply to owners of dispensaries and cannabis manufacturing and cultivation facilities. But Denver hoped that a delivery business would provide a more affordable pathway for people trying to break into the industry.

“We recognized that there were a lot of people who were disproportionately impacted by prohibition” of marijuana and weren’t benefitting like others after legalization, he said.

And people of color were disproportionately arrested and convicted, Escudero added.

People with marijuana violations on their records found it difficult to get into the new business after the drug became legal because of a federal priority to prevent criminals from profiting from cannabis. That led to rules excluding people with a criminal history from getting licenses, according to a report that includes information about Denver’s social equity program.

The social equity program also applies to those whose family members were arrested or convicted. The program offers advice on business plans, training, site visits as well as greatly reduced license application and renewal fees.

“The fact that weed is still illegal federally means people can’t go to a bank, get a loan and start a business,” Escudero said.

Getting a foot in the door

Legislation allowed Colorado communities to approve permitting for retail marijuana delivery starting in January 2021. The first completed deliveries by licensed companies in Denver took place in October 2021.

Other cities that allow cannabis deliveries are Northglenn, Aurora, Boulder, Longmont and Thornton, said Truman Bradley, who heads the Colorado-based Marijuana Industry Group.

In 2022, Denver revamped its regulations to encourage more participation in the cannabis-related business. In January 2023, there were 1,165 deliveries totaling $94,241.74 in sales. By March of that year, the number of deliveries rose to 1,246 totaling $ 105,732.89.

However, the trend has been mostly down for a while, hitting a low of 631 deliveries for $50,524.29 in sales in October. Deliveries rose slightly in November to 667, the first increase since January.

But overall, Colorado is experiencing “a marijuana recession,” Escudero said.

Medical marijuana was legalized in 2000 in Colorado. In 2014, the state became the first place in the world to legalize the sale of recreational marijuana. Statewide sales grew annually until peaking during the COVID-19 pandemic when the combined total for medical and recreational marijuana reached $2.2 billion in 2021.

Total sales across Colorado were $1.52 billion in 2023 and were $1.06 billion through September this year. Escudero said the downturn is likely because of a number of factors: inflation sapping people’s expendable income; the normal growing pains of an evolving industry; and competition from other states that have legalized cannabis.

“In the very early days of legalization, people would travel to Denver for the cannabis experience,” Escudero said. “Now that legalization has spread across the U.S. like wildfire, we think that could potentially be one of the reasons we’ve seen sales go down in Denver and Colorado.”

Twenty-four states and the District of Columbia allow the use of recreational marijuana. Another 14 states allow medical use only.

Along with keeping an eye on marijuana sales and the tax revenue generated for the city, Denver is tracking the state of the associated delivery business. Escudero said Denver has issued 23 licenses to transporters, or delivery companies. Just 14 of those are currently active.

Only 13% of Denver’s 188 cannabis locations have a permit for deliveries. Dispensaries can’t make their own deliveries. They must contract with a licensed delivery company.

“This recession in the cannabis industry couldn’t have hit at a worst time for these delivery businesses. We’re hoping that once the industry pulls out of this, there are still going to be some delivery companies left,” Escudero said.

The type of person we’re trying to help

Diaz-Rivera started his journey from felon to businessman when he was just 19. After graduating from high school, he was living out of his car.

“I was selling weed as a way to survive,” said Diaz-Rivera, now 39.

While driving on a Friday night in 2006, Diaz-Rivera was pulled over by police in the Colorado Springs area. He was arrested on charges of felony distribution of marijuana and pleaded to felony possession. He served a few months in jail, but was released to work. He also paid $3,000 in restitution.

Diaz-Rivera was working at a family fun center, which had games and an arcade. He said it was the only place that would hire him after his arrest. He discovered he had a passion for working with kids and wanted to be “a responsible citizen in the community.”

He earned an associate degree from Pikes Peak State College, transferred to Metropolitan State University of Denver and became a teacher.

“Even that at first was a problem because of my felony for a controlled substance, even though it was weed and weed was legalized at this point,” Diaz-Rivera said.

A shortage of teachers and a review of his resume, which included mentoring, landed him a job as fifth-grade teacher.

“Growing up in school, I was always a knucklehead: getting expelled, getting suspended,” Diaz-Rivera said. “As a teacher, those kinds of kids gravitated toward me because I had a similar understanding.”

But he started to feel burnt out while teaching from home during the pandemic. “I was a new dad, trying to figure things out. I wasn’t being paid enough from teaching and I was just not happy with the career,” Diaz-Rivera said.

He heard about Denver’s social equity program for those looking to get into the cannabis business.

“And I was like, ‘That’s my ticket to send my kids to college if I’m not going to be a teacher.’ I jumped in with both feet and started the entrepreneur lifestyle without realizing how risky it was,” the father of three recalled.

Escudero said Diaz-Rivera is the type of person Denver’s program is trying to help. “He’s turned his life around and he’s trying to run a successful business while facing really challenging times”

Diaz-Rivera is working with five dispensaries and has three drivers who are instructed in the regulations and security measures required by the job. He cut the drivers’ hours back after a “stagnant” summer, but is optimistic about the recent slight increase in deliveries. He said people like the convenience of food, clothes and other items delivered to their doors.

“So it only makes sense for us to get our weed delivered as well.”

However, Diaz-Rivera said there is resistance on the part of some dispensaries that might see delivery as cutting into their business. When customers visit a store, there’s an opportunity to upsell them, he said.

Escudero said another possible reason that deliveries haven’t taken off is that with 188 stores in Denver, many people don’t have to walk or drive far to buy cannabis.

Curtis Washington, owner of the Green Remedy dispensary, said he’s not worried about delivery affecting his sales. “People have access to your website so they can see what you have to sell. The only thing you’re missing is that local salesperson trying to upsell them.”

Even then, there are daily limits to how much a customer can buy and people’s own budgetary constraints, Washington said.

One of the reasons Washington uses a delivery service is that he wants to support Denver’s social equity efforts. Washington qualified for the program because of a family member’s arrest on a marijuana charge.

Diaz-Rivera said Denver’s program and the state Cannabis Business Office have provided him and others valuable technical assistance, help with business plans and access to resources. In a statement, the state office said it has supported social-equity licensed businesses through more than 3,500 hours of education, 66 grants that have helped create and retain nearly 300 jobs and 55 new businesses and seven loans supporting 18 jobs.

“The Governor’s November 1 budget proposal includes ongoing funding to continue this important work,” the business office said.

Continuing social equity programs is vital, Diaz-Rivera said. He said his arrest hurt his family financially and his ability to get work and find housing.

“There’s been a lot of harm from the war on drugs,” he said.

The effort to repair the harm is a win for the people affected as well as the overall economy overall, he added.

©2024 MediaNews Group, Inc. Visit at denverpost.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments